• Into the tourist trap

Antony Lambton

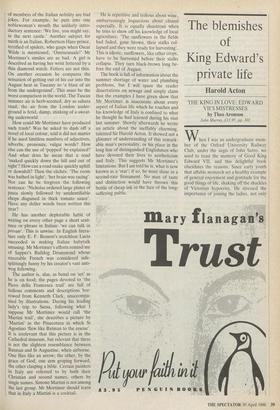

SUMMER'S LEASE by John Mortimer Viking, E11.95, pp. 289

Ihave always admired Mr John Mortim- er's portrait of his father and was sorry to be away last year when he visited my house in Italy. In my absence he charmed every- one. I must confess I am not charmed by his new book, Summer's Lease, an in- digestible lump of 'tourist' journalism. Fias he been corrupted by his commercial rela- tions with television, I wonder? This book could well have been the first uncorrected, unaccepted draft for a television program- me.

It starts off pretending to be a mystery related to Conan Doyle's Copper Beeches. The plot dies, other themes peter out, a number of unrealistic characters and a skilfully drawn old man move about aimlessly in a vacuum. The heroine — or rather chief female character — is dull. So are her husband, children, friends; but dullest of all is the author's habit of flaunting flags of lopal colour. If there is anything more boring than an Englishman ranting about bullfighting, it is anyone but a Sienese enthusing about their annual horse race, the Palio. Mr Mortimer falls headlong into this tourist trap. Worse, he endlessly refers to what he archly calls 'the Piero della Francesca trail' which ends in Urbino, described as being 'out of the mountains' on an endless plain. Anyone with eyes, who had been there, knows that the palace owes half its exterior beauty to its commanding position on top of a spur of the Appenines, looking down on the sur- rounding countryside.

I have said that Mr Mortimer's English characters are uninspiring. I-fis Italian character-sketches are worse, but are ex- actly what I would expect from a profes- sional class, left-wing, parlour pink who has for years — and on this trip — courted the company of milionaires. In other words, he has never admitted his love-hate for the rich and socially powerful. This unfortunate weakness makes him an unfair judge of the aristocracy, and his vignettes

of members of the Italian nobility are bad jokes. For example, he puts into one noblewoman's mouth the unlikely intro- ductory sentence: 'We live, you might say, in the next castle.' Another subject for mirth is an Italian, Robertson Hare prince, terrified of spiders, who gasps when Oscar Wilde is mentioned, 'Omosessualer Mr Mortimer's similes are as bad. A girl is described as having her wrist fettered by a thin diamond watch. Fetters are not thin. On another occasion he compares the sensation of getting out of his car into the August heat in Tuscany to 'a blast of air from the underground'. This must be the worst comparison in the world. The Tuscan summer air is herb-scented, dry as sahara sand; the air from the London under- ground is fetid, damp, stinking of a sweat- ing underworld.

How could Mr Mortimer have produced such trash? Was he asked to dash off a novel of local colour, told it did not matter if he used limitless numbers of adjectives, adverbs, pronouns, vulgar words? How else can the use of 'popped' be explained? And what does he mean that a road 'snaked quickly down the hill and out of sight'? How can a road snake quickly uphill or downhill? Then the clichés: 'The room was bathed in light'; ter brain was racing'. Nor can he be forgiven the following sentence: 'Nicholas ordered large plates of pasta slowly followed by unidentifiable chops disguised in thick tomato sauce'. Have any duller words been written this year?

He has another deplorable habit of writing on every other page a short sent- ence or phrase in Italian: 'we can talk in private'. This is unwise. In English litera- ture only E. F. Benson's matchless Lucia succeeded in making Italian babytalk amusing. Mr Mortimer's efforts remind me of Sapper's Bulldog Drummond whose execrable French was considered side- splittingly funny by his creator's vast anti- wog following.

The author is, alas, as banal on 'art' as he is on food; the pages devoted to 'the Piero della Francesca trail' are full of tedious comments and descriptions bor- rowed from Kenneth Clark, unaccompa- nied by illustrations. During his leading lady's trip to Siena, following what I suppose Mr Mortimer would call 'the Martini trail', she describes a picture by 'Martini' in the Pinacoteca in which St Agostino 'flew like Batman to the rescue'. It is irrelevant that this picture is in the Cathedral museum, but relevant that there is not the slightest resemblance between Batman and St Augustine, when airborne. One flies like an arrow; the other, by the grace of God, one arm groping forward, the other clasping a bible. Certain painters in Italy are referred to by both their Christian and second names, others by single names. Simone Martini is not among the last group. Mr Mortimer should learn that in Italy a Martini is a cocktail. He is repetitive and tedious about wine, embarrassingly loquacious about chianti especially. It is equally disastrous when he tries to show off his knowledge of local agriculture: 'The sunflowers in the fields had faded, gone brown, their stalks col- lapsed and they were ready for harvesting'. This is idiotic: sunflowers, like other crops, have to be harvested before their stalks collapse. They turn black-brown long be- fore the end of August.

The book is full of information about the summer shortage of water and plumbing problems, but I will spare the reader dissertations on sewage and simply claim that the examples I have given show that Mr Mortimer is inaccurate about every aspect of Italian life which he touches and his knowledge of Italy is confined to what he thought he had learned during his visit last summer. Shortly afterwards he wrote an article about the ineffably charming, talented Sir Harold Acton. It showed not a glimmer of understanding of this remark- able man's personality, or his place in the long line of distinguished Englishmen who have devoted their lives to aestheticism and Italy. This suggests Mr Mortimer's limitations. But I am told he is, what is now known as a 'star': if so, he must shine in a second-rate firmament. No man of taste and distinction would have thrown this bottle of cheap ink in the face of the long- suffering public.

Previous page

Previous page