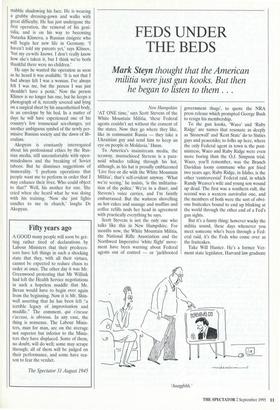

FEDS UNDER THE BEDS

Mark Steyn thought that the American

militia were just gun kooks. But then he began to listen to them. . .

New Hampshire 'AT ONE time,' says Scott Stevens of the White Mountain Militia, 'these Federal agents couldn't act without the consent of the states. Now they go where they like, like in communist Russia — they take a Ukrainian guy and send him to keep an eye on people in Moldavia.' Hmm.

To America's mainstream media, the scrawny, mustachioed Stevens is a para- noid whacko talking through his hat, although, as his hat is proudly emblazoned 'Live free or die with the White Mountain Militia', that's self-evident anyway. 'What we're seeing,' he insists, 'is the militarisa- tion of the police.' We're in a diner, and Stevens's voice carries, and I'm faintly embarrassed. But the waitress shovelling us hot cakes and sausage and muffins and coffee refills nods her head in agreement with practically everything he says.

Scott Stevens is not the only one who talks like this in New Hampshire. For months now, the White Mountain Militia, the National Rifle Association and the Northwest Imperative 'white flight' move- ment have been warning about Federal agents out of control — or 'jackbooted government thugs', to quote the NRA press release which prompted George Bush to resign his membership.

To the gun kooks, 'Waco' and 'Ruby Ridge' are names that resonate as deeply as 'Stonewall' and 'Kent State' do to Sixties gays and peaceniks; to folks up here, where the only Federal agent in town is the post- mistress, Waco and Ruby Ridge were even more boring than the O.J. Simpson trial. Waco, you'll remember, was the Branch Davidian loony commune who got fried two years ago; Ruby Ridge, in Idaho, is the other 'controversial' Federal raid, in which Randy Weaver's wife and young son wound up dead. The first was a southern cult, the second was a western survivalist one, and the members of both were the sort of obvi- ous fruitcakes bound to end up blinking at the world through the other end of a Fed's gun sights.

But it's a funny thing: however wacky the militia sound, these days whenever you meet someone who's been through a Fed- eral raid, it's the Feds who come over as the fruitcakes.

Take Will Hunter. He's a former Ver- mont state legislator, Harvard law graduate Aaagghhh.' and lunch companion of Peregrine Worsthorne. That last bit, which admitted- ly his recent profile in the Valley News didn't go heavily on, came about when Hunter was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford and rented digs from the Conservative MP Sir Philip Goodhart. Under the onerous tax regime prevailing in Britain in the late Seventies, Sir Philip found it more conve- nient to collect a monthly rent paid in whisky, and, in return, Hunter and his room-mates were occasionally invited to the main house for lunch with his visiting grandees.

Afterwards, Hunter could have had his pick of the big city law firms. Instead, he returned to Vermont and became a coun- try lawyer, defending those sad, straggle- bearded losers with beat-up pick-ups who live anonymous lives in tar-paper shacks on the edge of White River Junction, until they're picked up on sex abuse or dope charges. For a hotshot attorney willingly to choose those clients over O.J. or Exxon probably does look suspicious when fed into a Federal computer, even before you throw in associations with dangerous sub- versives like Peregrine Worsthorne.

Even so, the events of Friday 9 June came as a surprise. At 3 a.m., on a sleepy back road in the Black River valley, the Hunters were woken by a pounding on the door and the entrance of seven agents from the Drug Enforcement Administra- tion in bullet-proof vests. The next day, Vermonters heard from DEA man James Bradley that Hunter had been fingered for laundering drug proceeds: 'It is clear from the testimony of a co-operating informant that Sargent and Hunter had worked together to launder Sargent's money.' No 'allegedlys' there, no 'helping police with their inquiries', no due process. Just: 'It is clear.'

In Chicago's Cabrini Green housing projects or the snow belt of south Florida, drugs raids are the urban equivalent of chirruping cicadas, part of the soothing lullaby of the night. But in Vermont, sec- ond most crime-free state in the Union, the Hunter raid was unprecedented. Dis- appointingly for the DEA, which seized hundreds of files and four computers (including those of Vermont Law Week, which Hunter publishes from his base- ment), no one else seems to think he's laundering anything. The line taken by the crusty old Yankee at the store is that Hunter can't even launder his pants, which, unlike the DEA statement, has the merit of being a proven fact. His clothes come from the annual Weathersfield rum- mage sale, and he greets me at the door without shoes — the first barefoot lawyer I've ever met.

My initial reaction is to say, 'Wow! The Feds really tore the place apart,' but, on closer inspection, it turns out that most of the debris in his cheerfully dishevelled home-cum-office is the kids' toys, the pet turtles and other detritus from the Hunters' unlaundered life: the neighbours deeded them an adjoining ten-foot strip of land, but on condition they keep that side of the lot clear of junk. Hunter makes $20,000 a year and, taking a leaf out of Sir Philip's book, will accept payment in cheese and maple syrup.

It's the clash of cultures you're struck by: the DEA men shone flashlights on Hunter's kids and in-laws, and demanded to know where he kept his weapons; his wife, April Hensel, was more preoccupied in getting the Feds to keep the basement door shut so that the cats wouldn't get out and savage the chicks in her daughter's bedroom. 'I suppose, if you're a DEA agent, Vermont isn't the most exciting posting,' she says sympathetically, showing me, as she showed the DEA, the turtles in the bathtub. Happily, in defiance of the prevailing trend when Federal agents come a-callin', in this instance they left behind no dead women or children, or even poultry.

What impressed the locals was, as at Waco and Ruby Ridge, the sheer lavishness of the strike: Branch Davidians, Rocky Mountain white separatists, eccentric Ver- mont lawyers — they may all be nuts, but you marvel at the number of sledgeham- mers Federal law enforcement can muster to crack them. In this neighbourhood, pub- lic service is local and voluntary. Across the border in New Hampshire, my town can afford one cop whose accounts are scrupu- lously mailed to every resident:

Item 4: Cruiser Usage Miles driven: 9,881 Gasoline consumption: 761.5 Average miles per gallon: 13.5.

In Cavendish, as everywhere else, the fire departments consist of volunteers; in Thet- ford, Vermont, this month, the townsfolk turned out in force to erect -7 like an old- fashioned barn-raising — a new fire sta- tion. Yet the Federal government, apparently, can afford to pay a fully armed DEA team, accompanied by a US attorney and two customs officers, presumably all on overtime, to swoop down in the middle of the night on a small-town lawyer. Let's assume Hunter's guilty: you can guarantee that the money he's laundered will be sig- nificantly smaller than the cost of the raid.

That's the history of the DEA in a nut- shell: in the two decades since President Nixon declared the 'war on drugs', the DEA have been given more and more money, more and more resources and more and more powers — and the net result is that we have more and more drugs, and more and more drugs-related crime. By any standards, the DEA must be considered the most spectacular failure — yet they're less accountable than my town's one-man police department.

'I didn't even know there were Vermont DEA agents before this happened,' says Hunter. 'They're not part of the communi- ty, they're like flotsam on the pond, uncon- nected to anything. Who's this guy Bradley who slammed me in the papers? Who does he answer to? If it were some local cop, you could call up the chief and say, "Hey, this guy's totally off base." I don't know who to call about this . . . '

It's true, the DEA aren't listed in Hunter's book. I try Vermont directory assistance and get some Justice Depart- ment automated touch-tone 'press number four if you want to visit Canada' junk. Then I try again.

'Bradley,' answers Bradley. Good grief. James Bradley, DEA agent-in-charge for Vermont and a mere hundred miles upstate from Cavendish. It's that easy. And, after an obligatory 'no comment', he proceeds to comment away merrily. So why didn't the DEA go round at 9 a.m. instead of 3 a.m.? Makes it less of a 'raid', more of an 'appointment'?

'That's not the way we do things,' he says.

So the DEA doesn't distinguish between raiding coke traffickers in south Miami and a family home in rural Vermont? It's all the same — bullet-proof vests and all?

'Mark, it was perfectly proper,' sighs Agent Bradley. Even the vests? 'They wore those uniforms because they were on their way from another raid.'

I ask him why, almost two months after she wrote, Hunter's wife has had no reply to her letter to Janet Reno, head of the Justice Department.

'If someone in England wrote to the Queen,' says Agent Bradley, 'would they get a reply?'

Well, from a secretary, an acknowledge- ment or something. . .

'Mark, she sent it to Janet Reno, Senator Leahy, Congressman Sanders, the head of the DEA, the head of US Customs, she sent it to everyone in the world. Do you take a person like that seriously?' The letter is lying on his desk and he quotes from it.

But hang on. The Justice Department's official position, as stated on CBS Televi- sion, is that no letter was ever received . . .

Over the telephone, Agent Bradley is charming and a lot chattier than his British equivalent would be. But you can hear in his answers the assumption that Mrs Hunter, who works for the state envi- ronmental commission, is some kinda flake. Even if she were, would that justify not answering her letter? Increasingly, government officials seem to take pleasure in smearing their opponents. When speak- ing to Mrs Hunter, I mentioned Federal claims that the Waco cult was a hotbed of sex'n'substance abuse. The following day, President Clinton commented gravely that all Americans would be 'shocked by the depravity of what was going on in that compound'. 'Yeah, right,' says Mrs Hunter scornfully. 'There's children being abused in there, so let's go in and put a stop to it by killing them.'

'If they whack someone, they're going to cover themselves by smearing the guys they've whacked,' says Scott Stevens back in the militia booth at the diner. When dis- cussing Waco, he eschews the word 'com- pound' and prefers 'homestead', which, in truth, whenever you see it burning on tele- vision, is what it looks like. 'With Randy Weaver, they were bugging him for days, trying to get him to sell them a sawn-off shotgun. So eventually he did. Then, when they said they were ATF [Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agents], he said it was entrap- ment. That's why he wouldn't appear in court. So they besiege his property, and this one agent, Lon Horiucci, "accidental- ly" kills the guy's wife with a specially out- fitted sniper rifle at only 200 yards.' Stevens laughs. 'You ever shot anyone acci- dentally with such a sophisticated outfit?'

'Well, no,' I laugh back. I don't add that I've never shot anyone, accidentally or oth- erwise, in case he thinks I'm a wimp. But I get his drift.

'These people in Drug Enforcement and Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms,' says Will Hunter, 'wrap the shroud of national secu- rity around them. There isn't any commu- nist threat any more, so it's not the military and the CIA, but the Feds are the Nineties equivalents: they have this mission that they're on, and they think they can do whatever they want.'

Leaving his house, I take a deep gulp of Vermont air and savour the still of the night. In the next valley, no doubt, one of those hippy draft dodgers who scrammed to Vermont back in the Sixties is lighting up a joint. But, if I had to choose, I'd say that the corrosive, corrupting force here is Federalism. Intentionally or not, it reduces everything to the worst-case scenario, so that, for a few hours one Friday morning, it policed small-town Vermont as if it were drug-infested Miami. 'Reds under the beds' was supposedly McCarthyite paranoia. But Feds under the beds? They're there.

'It's only temporary till they find room in solitary.'

Previous page

Previous page