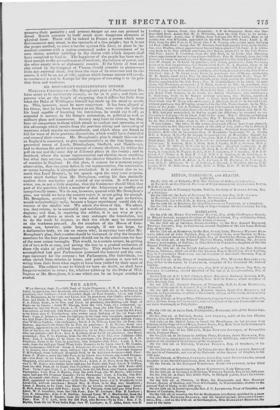

THE PRESS.

THE NETHERLANDS.

Monier:eta CuttotaienE—The King of the Netherlands may not be an evil-intentioned mail; but he is evidently a very weak man. Ass constitutional king, he ought not to have quibbled with the people about ministerial responsibility. What is a constitutional government, indeed, without ministerial responsibility ? His Ministers were mere creatures —so many clerks whom he appointed or turned off without ceremony ; and the people were thus deprived of all knowledge of their own affairs. He used to chuckle at the advantage he had over the King of England, in being his own minister, and having everything as much his own way-as if he were a Duke of Brunswick. Ile has now paid the penalty of his folly,—for we hold it impossible for him ever more to become Sovereign of Belgium. Had he known how to yield in time—had be admitted that the construction he put on the votes of the Belgian Notables was an unfair one—that the nation was from the first hostile to an union with Holland—had he met the Belgians candidly, he might have reigned over Belgium as well as Holland, though the two countries were sepa- rate. Had he even pursued his system of delay, it is ten to one that the Belgians would have been wearied out, and that want of employment and diminished earnings would have cooled the ardour of the working classes, and commercial embarrassment the middling classes. But he became too impatient of the delay attendant on this system, and nothing less would serve him than reducing Brussels by force. This might have been successful had the discontent been confined to Brussels. But the discontent is common to nearly four millions of warlike inhabitants, who, from the density of the population, can easily act on any given point ; and the utter destruction of the whole population of Brussels would only have strengthened the opposition to the Royal authority, and given to it a fiercer and more determined character. He has by this time found, that every Belgian slain is a victory over his own authority. The lesson will be useful. The King of the Netherlands may not have been the worst of the Kings of Europe, but he has, nevertheless. de- ceived his subjects ; he has denied to them the knowledge of public affairs; he has stood out for practices irreconcilable with constitutional government—such as issuing cabinet orders with the force of law ; he has denied to his subjects jury trials ; he has chosen to control them in the exercise of their just and lawful freedom. Having refused to alter his conduct, he will be cashiered, and the attack on Brussels will cause him to be detested from one end of Belgium to the other. With respect to other Powers, we hope they will not be so imprudent as to interfere with the Belgians in this warfare. If allowed to settle the affairs themselves, all may be well ; but if England and Prussia take part in the fray, adieu to all hope of preserving the peace of Europe. War in Europe at this time would everywhere lead to revolution. But the knowledge of this will, we trust, impress the rulers with a desire of peace. No man knows where the flames would stop. The people of this country—the industrious population—have no interest in the pre- servation of those fine schemes of settlement of Europe, in the arrange- ment of which Lord Castlereagh and the Duke of Wellington acted so conspicuous a part. What is it to the people of England whether Bel- gium be united to Holland or separate from Holland? The less we in- terfere with the Continent the better. Our Government has more on its hands at home and in our numerous Colonies than it can do justice to. The people of England will never forgive the Minister who hazards the safety bf the country by any Continental interference.

THE STANDARD—The Globe of last night is merry and severe upon us for anticipating that Brussels would submit, or that it must be shelled and burned. We should, says our pleasant contemporary, as soon ex- pect to hear that it had been "skinned and eaten." Cities have, how- ever, subtnitted—cities too have been shelled and burned ; but we Lave ItTzer heard of a city eaten, save by an earthquake. * * * We are, it seems, worthy of reprehension, because we anticipated the reduction Or punishment of the Brintellois with " a degree of joy." We do not deny it ; we did anticipate the defeat and punishment of these traitors to the rights and interests of the human race with a great degree of joy, and we will tell the Globe the reason of our satisfaction. It is because. they are acting to vulgar understandings, that is, to the million—the apology for every base and wicked tyranny ; they are performing the defence of Charles the Tenth,—for how many will say that, even had he. not Played the despot, the same spirit that rises against a good king at Brussels would have risen against him. They are exhibiting a posthumous justification of the atrocious principles of the Holy Alliance, by showing, as far as they can, that good government cannot secure the peace of the European commonwealth, without a superintending despotism. They are furnishing the sons of corruption in England, too, with arguments in behalf of their system, when that System has approached its last agonies. Such arguments, we admit, ge- nerally address themselves to vulgar minds only,—better natures will not obviate crimes by committing them,—but we fear the destinies of nations will be for ever swayed, as swayed they ever have been, by vulgar minds. And we find even the virtuous and the wise begin. fling to doubt whether a perfectly pure administration, and a per- fectly free press, can co-exist with a settled government. This the Brnxellois have done; and they have done more than this—they have taught Kings the danger of showing forbearance or mercy in civil war. If they succeed in their present struggle, ultimately, they cannot prevail, we may look for centuries of bondage, and ignorance, and barbarous oppression on the continent, and of corruption and misery in England. It is, therefore, with a very high degree of joy that we anticipate the punishment of these enemies of all nations ; and we trust that, if they receive it not at the hand of their master, they will receive it from the Powers that have guaranteed his throne. France cannot, without open and profligate perfidy, recede from her share of the en- gagement ; and Prussia, we may be sure, will be prompt to fulfil hers. It has been said, we know, that France will assist the rebels ; but Franco is bound by treaty to act against them. The chan.geof her institutions, or her dynasty, does not in the least exonerate Iler from the oblige- - don. If the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of an independent country be acknowledged, the immutability of ex- ternal obligations by any internal change follows as a necessary corollary. If the Allied Powers could be placed in a worse con- dition by the change of affairs in France, it is plain that that circumstance gave them a right to prevent such a change which the French people will scarcely admit. France owes it to Europe to discountenance the traitors; and we may add, that no country in Europe has so much to fear from rekindling a war as France herself. The next European war which France shall provoke will be acted in her own bosom. Experience has shown the policy, and providence has fur- nished the means, of such a prosecution of hostilities, if France make hos- tilities necessary, which heaven avert. The mighty engine, steam navi- gation, of which England has possessed herself within the last ten years, throws the whole seaboard of France open to her armies and the armies of her allies. The British Ministry would deserve impeachment that should leave a stick standing in any French port within three months of the commencement of a war. Expeditions would not be again six months in preparation, to be three months in doubt, and to fail in-three days ; at any time fifty thousand men, say English, Prussian, Dutch, or others, might in a week be laid ashore, upon any part. .of the French coast, where 'attack was least provided againet:'We should have no more sieges of Bergen-op-Zoom Antwerp, Boinmel, or Valenciennes; the heart of France would be the scene of operation. Paris might again see an alien flag displayed upon Mont-Martre, or, even without being eaten, prove that fate from which, as the Globe inti- mates, all great cities are as completely exempt. But we hasten from contemplating such a horrid hypothesis as a European war, though we cannot help thinking that the jacobins of Paris ought to be taught that their present condition is not quite so promising as it was in 1792, or even as it was in 1814. Of the good sense, however, of the King, and of the intelligent part of the nation, there can be no doubt. (Oct. 1.) THE GLOBE—The die is cast. If the Southern division of the Ne- therlands is to remain united with Holland, it must be on terms which the people of Belgium, treating as an independent body, will consent to —unless, indeed, there should intervene in the quarrel other Princes and Generals than Prince Frederick and Kort Heiliger ; unless, in short, some of the great rowers of Europe should reconquer Belgium by an overpowering force. This is the point of greatest importance to our- selves. The Belgians, if foreign powers do not interfere, will settle their own affairs as may best suit their inclinations ; but if, for the pur- pose of preserving intact the fantastic arrangements of the Congress of Vienna, the people of Belgium are to be crushed by some of the great powers of Europe, who can see the end of the evil ? Reports are already spread that the Government of the Netherlands has applied to this country for assistance. These may be premature ; but it cannot be premature to warn the people of Europe against the consequences of foreign interference with Belgium. There can, we are satisfied, be no engagements by which England can be bound to interfere between the people of Belgium and the Government; but it must be foolish in the present posture of affairs for any Power to do so. The only pretext for such an interference would be the value, by way Of protection for Europe against France, of the fortresses of the fron- tier line ; but the recent events exemplify, in the clearest manner, the consequences which would ensue in respect to these fortresses from forcing upon the Belgians an unpopular form of government. If the Belgians are not appeased, but subdued or overawed, they would merely wait their time • the declaration of a war would be a signal for the peo- ple to take the &tresses, as they have shown themselves able to do now, and the fortresses, instead of being defences against the French, woul& he points of support for them. They can only be of use as defences for Europe if in the hands of a popular Government ; not in the temporary possession of a Sovereign who would find them exposed on the first danger, to more formidable assaults from within than from without. It cannot, too, escape provident' politicians, that France is not the power from which the present inhabitants or Europe need be most anxious to preserve tNeir posterity ; and present danger no one can pretend to dread. Russia contains in itself much more dangerous elements of physical force. There will be indeed in France a power which some Governments may dread, in the spectacle of a free people; but it is not the proper method, to erect a barrier against this force, to place in im- mediate contrast with a nation contented under a Government of its own choice, another writldng in the chains with which despots shall have conspired to bind it. The happiness of the peciple has been sacri- ficed enough to the arrondissement of territory, the balance of power, and the other empty idols of diplomatic conceit. If the fabric of iron and clay raised by the Congress of Vienna should crumble to pieces—not from any external shock, but from the vices of its structure and its ele- ments, it will be an act of folly, against which human nature will revolt, to commence a war in Europe for the purpose of restoring it to its pris- tine form and weakness.

RitouGHAm's. PARLIAMENTARY REFORM.

MORNING Cunoxi e LE—Mr. Brougham's plan of Parliamentary Re- form seems to be satisfactory enough, as far as it goes ; and there are persons who go the length of supposing that it differs but little from what the Duke of Wellington himself has made up his mind to accede to. This, however, must be mere conjecture. It has been alleged of his Grace, that he has been known to say that, were even the hair on his head capable of knowing his intentions, he would cut it off; so essential is secrecy, in his Grace's estimation, to political as well as military plans and mametwres. Secrecy may have its virtues, but they bear no comparison to those which attach to candour and openness, or to the advantage which results from the previous sifting and canvassing of measures which require no concealment, and which often are found to fail for want of these previous discussions, which would have dovetailad and secured their success. Mr. Brougham's plan is simply this—as far as England is concerned, to give representatives to the four large unre- presented towns of Leeds, Birmingham, Sheffield, and Manchester, and to shorten the period and expense of county elections, by taking the poll on one and Ow same day at different places in the county; and in Scotland, where the terms representation and election mean anything but what they express, to assimilate the elective franchise there to that of counties in England. In this plan, it cannot for a moment escape observation, that one great defect in our representation, the nomination or rotten boroughs, is altogether overlooked. It is curious also to re- mark that Lord Morpeth, in his speech upon the very same occasion, went much further than Mr. Brougham, setting his face decidedly against these mockeries and scandal of our system. It will occur to some, too, as not a little singular, that the Commoner should blink that part of the question which a member of the Aristocracy so readily and unequivocally meets. We do not, however, quarrel with Mr. Brougham's plan, nor would we have the country reject it as not going far enough. Mr. Brougham, probably if be were asked why he goes no further, would unhesitatingly reply, because a larger experiment would risk the success of the smaller one. We admit the force of this. We admit, too, that reform, to be successful and satisfactory, must be a work of degrees ; and that, in repairing the edifice, it is not wise or urn- dent to pull down as much as may endanger the foundation, but to do the work by degrees, so that the whole may be reinstated as the workmen proceed. As the numbers of the House of Com- mons are, however, quite large enough, if not too large, for a deliberative body, we see no reason why, in carrying into effect Mr. Brougham's plan, their number should be increased, or why the intended members for the four places named should not be the substitutes for four of the most rotten boroughs. This would, to a certain extent; be getting rid of two evils at once, and paving the way to a gradual extinction of these vile sinks of political depravity. This might have been already accomplished had past Parliaments possessed the honesty and the cou- rage necessary for the purpose ; but Parliaments, like individuals, too often shrink from reforms at home, and public opinion is now left to wring from their fears what ought to have been yielded by their sense of justice. The subject is one to nitic,h we have no doubt, we shall have frequent occasion to recur; for, whether talc-en up by the Duke of Wel- lington or Mr. Brougham, it is one which can be no longer avoided or evaded.

Previous page

Previous page