Sensitive to the drama of light

Martin Gayford says look at Gainsborough's terrific pictures, and don't read the labels

f a portrait 'happened to be on the easel', wrote Henry Angelo of Thomas Gainsborough, 'he was in the humour for a growl at the dispensation of all sublunary things. If, on the other hand, he was engaged in a landscape composition, then he was all gaiety — his imagination was in the skies.' What Angelo doubtless meant was that the painter's creativity rose like a balloon into the air. But, looking at Gainsborough's work assembled at Tate Britain in a huge retrospective (until 19 January), one might be excused for taking his words literally.

Take a step back from the early paintings in the first room, and you become overwhelmingly aware of their skies. At this stage, the young painter was clearly under the influence of 17th-century Dutch masters, Ruisdael especially, but his cloudscapes are personal and touching. Tender, dove-grey as much as blue, with a Mozartian mixture of sunshine and shadow, in some cases darkening to mulberry with approaching rain, they give drama and emotional tone to the pictures. As John Constable — another great painter from East Anglia — later put it, the sky is the chief organ of sentiment' in each of these little paintings.

This was also the case quite often later on, when Gainsborough had become a fashionable portraitist in Bath and London. Captain William Wade, Master of Ceremonies at the Bath Assembly Rooms, stands tall and foppish in front of a huge expanse of light and air with only a bracket of classical stone separating him from infinity. Mary, Countess Howe is illuminated — as if by a flash of lightning or ray of sunset — against a rapidly gathering storm.

Behind Isabella, Viscountess Molyneaux, the heavens are even darker.

Some of my critical colleagues have grown equally thundery in contemplating the words that accompany this exhibition. In the catalogue, it is true, the curators are inclined to push the sociological and sexual political aspects of Gainsborough's art in prose larded with the jargon of the new academese. Of the early 'Revd John Chafy Playing the Violincello in a Landscape', for example, they note: 'Appealing as the resulting image is, it is worth remembering its serenity was predicated upon the social status and gender of the sitter.' Well, perhaps, yes, but whether holding such platitudes in one's head really helps the understanding of Gainsborough is another question.

The paradox is that sociological art history is not particularly exhibitable, whereas pictures are. The information offered is irritating only if you read it. Personally, owing to instinctive anarchism, I almost never notice it (and would pay a stiff fee not to have to listen to a tape-recorded guide). Consequently, 1 went round the whole show just looking at the pictures, which are admirably selected and hung, and didn't get so cross. While not reading what I was supposed to be reading, my attention was caught by such things as skies, clothes and dogs.

Gainsborough was evidently an artist who was acutely sensitive to the drama of light. The catalogue is not a complete write-off. If you plough through the Seventies-style politics a good deal can be learnt, particularly from an excellent essay by Rica Jones and Martin Postle on Gainsborough's methods and techniques.

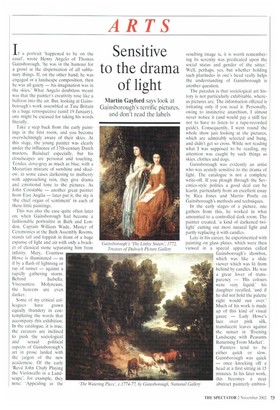

In the early stages of a picture, one gathers from this, he worked in what amounted to a controlled dark room. The painter created, 'a kind of darkened twilight' cutting out most natural light and partly replacing it with candles.

Late in his career, he experimented with painting on glass plates, which were then viewed in a special apparatus called Gainsborough's showbox, which was like a slide viewer which was lit from behind by candles. He was a great lover of transparency — 'His colours were very liquid,' his daughter recalled, 'and if he did not hold the palette right would run over.' Much of his work is made up of this kind of visual gauze — Lady Howe's lace over pink silk, translucent leaves against the sunset in 'Evening Landscape with Peasants Returning From Market'.

Painters tend to be either quick or slow. Gainsborough was quick — once knocking off a head at a first sitting in 15 minutes. In his later work. this becomes a near abstract painterly embroi

dery, or even performance art ('Tis actual motion', reported someone who saw him at work on drapery, and done with such light airy facility. Oh, it delighted me when I saw it'). This, like the love of transparency, lent itself to the depiction of actual dress. Many of these paintings record meetings with remarkable clothes.

They are also full of animals. Gainsborough loved dogs particularly — painting a marvellous portrait of his own pet and his wife's 'Tristram and Fox'. Often his commissioned portraits are enlivened by an almost comic interplay between sitter and dog.

The Reverend Henry Bate strikes a pose while his companion waits for him to throw that walking stick he is elegantly leaning on; Henry, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch sits with equally mournful canine friend. These animals are as carefully studied as the people, if not more so (there is a report of piglets scampering in the artist's painting room about the time he was executing 'Girl with Pigs'. 1782).

The people too often have a sharp-eyed animal vitality — although, especially late on, they are altogether too gauzy and elegant for rue. It is hard to think of a painting of the nude with less sense of carnal physicality than Gainsborough's 'Diana and Actaeon'. But he certainly could be a great portrait painter — the unfinished picture of his daughter with a ghostly, feral cat is akin to Goya in its juxtaposition of innocence and feline savagery.

Gainsborough found ways to infuse his own sensibility — with its inclination towards lightness, humour, quickness, musically rhythmic brushwork, bright-eyed animality and bitter-sweet sadness — into commissioned portraits. Despite his professed preference for landscape, I don't find his landscapes better than the pictures of people; on the contrary, they tended to become mawkish and artificial.

Nonetheless. I think we should believe Gainsborough when he expresses his frustration at painting endless 18th-century Sloane Rangers (Now, damn gentlemen, there is not such a set of enemies, to a real artist, as they are, if not kept at a proper distance'). As you walk round, you feel he did too many portraits and should have followed his fancy more and 'picked pockets' less by lucrative facepainting.

Gainsborough, like many painters, was a clever, acute, gifted man: but not an intellectual. He preferred the company of musicians — he was a keen amateur himself — and actors to other artists and writers, and wittily deflated the pompous theorising of his rival and contemporary Joshua Reynolds. If he were still around, I suspect he would have banned the texts from this exhibition — as Lucian Freud did for the preceding show — and bluepencilled most of the catalogue. But his paintings look terrific, which is the only really important thing.

Previous page

Previous page