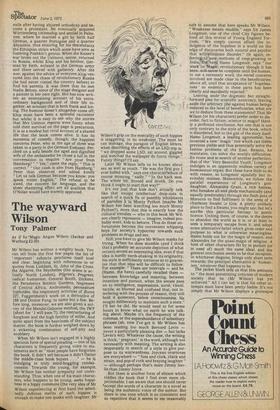

The wayward Wilson

Tony Palmer

As if by"Magic Angus Wilson (Secker and Warburg £2.50) Mr Wilson has written a weighty book. You can tell from the first few pages the list of ' important ' subjects proclaims itself loud and clear, beginning with references to or quotes from Luddism, St. John of the Cross, the Algarve, the Seychelles (the scene is ac'tually North London), Pilgrim's Progress, 'radical humanism, General Booth, Dickens, the Peradeniya Botanic Gardens, Negresses of Central Africa, Andromeda, pen nesitum typhoides, the respiratory activities of Jhona 227, Fuggersheim's work on a derivative of 188 and Doctor Fung, to name but a few. Before long, moreover, we are also given a survey of the Mendel-Osborne method, the IWP (short for '1 will pass '?), the restructuring of Sorghum and the high fertility of millet. And quite apart from the heaviness of the subject matter, the book is further weighed down by a sickening combination of self-pity and snobbery. When Mr Wilson isn't engaged in a highly specious form of special pleading — one of his characters is frequently giving voice to statements such as "most people have forgotten the book. It didn't sell because it didn't flatter the middle-class book buyers . . ." — he is indulging in truly mind-boggling condescension. Towards the young, for example, Mr Wilson has neither sympathy nor understanding. Thus, when one of his main characters, who happens to be young, seeks happiness in a hippy commune (the very idea of Mr Wilson experiencing at first hand the admittedly dubious merits of such hippies is enough to make one quake with laughter. Mr , Wilson's grip on the mentality of such hippies is staggering, in its weakness. The most he can manage, this paragon of English letters, when describing the effects of an LSD trip is: "we dropped some LSD, sat around, giggled and watched the wallpaper do funny things." Funny things? I'll say.

Later Mr Wilson tells us he knows about sex as well as youth. "He was the first guy I ever balled with," says one characterlwhois of course moaning "sadly." "In the back seat. The whole bit. Stoned and drunk. Do you think it ought to start that way?"

It's not just that kids don't actually talk like that except intellectual drop-outs in search of a quick fix or possibly inhabitants of parodies a la Monty Python (maybe Mr Wilson has been watching too much Monty Python?), more that this is exactly how the cultural trendies — who in this book Mr Wilson clearly represents — imagine, indeed probably want, kids to behave. Thus do these unfortunates become the convenient whipping. boys for society's hypocrisy towards such problems as drugs and sex.

Still, you have to give Mr Wilson marks for trying. When he does stumble (and I think that's probably an accurate depiction of what occurs) across an interesting idea, even if that idea is hardly earth-shaking in its originality, his style is sufficiently tortuous as to guarantee that that idea will be difficult to follow. For example: "There are intervals — and he (Hamo, the hero) carefully recalled them — between knowledge and meaning, between intention and pursuit, when the senses pass on to intelligence, impressions, aural, visual, tactile, so blurred and confused that, not interfering with the process of reason, they still hold it quiescent, below consciousness. He sought deliberately to maintain such a state." I'll bet he did. He would need to for some hours to know what on earth he was talking about. Maybe it's the frequency of the commas, or the superabundance of subsidiary phrases (ah, now I've got it: Mr Wilson has been reading too much Bernard Levin — never a particularly pleasing diet — but lacks levin's wit). Whatever the cause, the writing is thick; ' pregnant ' is the word, although not necessarily with meaning. The writing is also desperately in search of a style to give purpose to its waywardness. Joycean overtones are everywhere — "fuss and clink, clank and strain, and pop of cork and braying laughter" — although perhaps that's more Jimmy Savile than Jimmy Joyce.

But there is another form of elitism which riddles the book that I find even more objectionable. I am aware that one should never `accept the words of a character in a novel as being the authentic voice of the author. But there is one tone which is so consistent and so repetitive that it seems to me reasonably safe to assume that here speaks Mr Wilson. "Weakness means muddle," says Sir James Longmuir, one of the chief City figures behind all this revival of Young England Toryism; "We simply cannot afford the indulgence of the hopeless in a world on the edge of discoveries both natural and psychic that will :eliminate disorder." Or again, referringto 'new methods of crop-growing in India, the Them Hamo Longmuir, says "our work on 'Magic, revolutionary though it has been, will never be complete until the human, to use a necessary word, the moral concerns involved are made clear to the beneficiaries; above all, until that acceptance of ' hopelessness' so endemic in these parts has been clearly and manifestly rejected."

Leaving aside the dogmatic but straightforward plea for scientific autocracy, leaving aside the arbitrary jibe against human beings reduced to the level of beneficiaries, what are we to deduce from these statements? That Mr Wilson (or his characters) prefer order to disorder, fact to fiction, science to magic? Hardly a profound conclusion, but one that is not only contrary to the style of the book, which is disordered, but to the gist of the story itself. Hamo Longmuir, a leading agronomist, has invented a new ' magic ' rice which can treble previous yields and thus potentially solve the famine problems of the East. Reason, he maintains, can solve the world's difficulties. En route and in search of another perfection, that of the' Very Beautiful Youth,' Longmuir indulges in an apparently endless variety of homosexual orgies. But these have little to do with reason, as Longmuir squalidly but inevitably realises. Meanwhile, we follow the parallel experiences of Longmuir's goddaughter, Alexandra Grant, a rich heiress, who forsakes all and plods mechanically (and equally predictably) through the flesh-pots of Morocco to find fulfilment in the arms of a charlatan Swami ;n Goa. A pretty unlikely place to find a Swami, you might say, but let's ascribe this particular fantasy to poetic licence. Uniting them, of course, is the desire to abandon the world as it is, or at least to seek a temporary escape from it, and adopt some alternative belief which gives order and purpose to what is otherwise meaningless. Hamo holds out for the magic of reason, and Alexandra for the quasi-magic of religion. A host of other characters flit by in pursuit (or in need of) much the same ideal, and the general conclusion seems to be that escapism, in whichever disguise, brings only short term rewards; the principal alternative is humanism,' whatever that happens to be. The jacket blurb tells us that this amounts to "the most penetrating criticism of modern society that he (Mr Wilson) has yet achieved." All I can say is that his other attempts must have been pretty feeble. It's not simply that Mr Wilson displays a grotesque

ignorance of whole areas of society, from big business to hippies, which for the purpose of his thesis he needs to describe, but that as a writer he seems imprisoned in the mannered elitism and intellectual arrogance that characterises many Englishmen whose proclaimed subject matter is ' important ' or 'weighty' and whose books can't sell because "they don't flatter the middle-class audience."

In Mr Wilson's case I would hardly have thought this last objection justified. He has achieved a degree of social and therefore cultural acceptability which guarantees him publication, reviews and sales, however unjustified that acceptability may be.

Previous page

Previous page