Exhibitions 2

Faszination Venus (Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne, till 7 January 2001)

Take a girl like Venus

Nicholas Powell

ne day round about 1813, J.B.S. Morritt of Rokeby Park in Yorkshire spent a happy afternoon having his servants hoist Velazquez's 'Vends' — 'my fine picture of Venus's backside' — into position in his library. As he wrote to his friend Walter Scott:

It is an admirable light for the painting and shows it to perfection, whilst raising the said backside to a considerable height the ladies may avert their downcast eyes ... and con- noisseurs steal a glance without drawing the said posterior into the company.

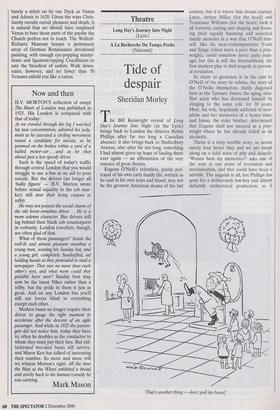

Faszination Venus, which transfers from Cologne to Munich and then to Antwerp, fields an impressive number of back and indeed frontsides of that quintessential beauty, goddess of love and fertility. Now in London's National Gallery, the Rokeby Venus (1650) is one of several master- pieces conspicuous by their absence. But the lay out of the exhibition is so intelli- gently and scientifically conceived (in nine sections, each respecting a major icono- graphic representation of the goddess) and the general standard of works so high that it does not really matter. Botticelli's 'Birth of Venus', for example, is not there, but a Botticcelli workshop standing figure of Venus, circa 1486-88 is — remarkably close in looks to the scallop-born version, she has the same gentle sway of the hips and covers herself modestly with a lavish length of hair.

Not surprisingly, given her family back-

ground (born of the sea from the foam pro- duced by the bollocks of the castrated Uranus, according to the Greek poet Hes- iod), Venus was not a nice girl. When not lolling around on sofas as an object of ado- ration, half-heartedly repelling satyrs (Sebastiano Ricci's 'Venus surprised by a satyr' 1710) or doing a brazen bit of finger- ing and thinking (Titian's 'Venus of Urbino', represented here by a 19th-centu- ry copy), she could be very vain, too. The iconographic theme of Venus looking at herself in a mirror was particularly pleasing to the French, as we see in the section 'The Toilet of Venus' with works ranging from two 16th-century Fontainebleau school paintings, both elegant exercises in upper- class nudity, to Simon Vouet and Charles Mellin's languid, somewhat melancholy work of 1626.

Vanity was the perfect excuse for pro- ducing female nudity au gout du jour — hence the tooth enamel-stripping sugari- ness of the 1746 canvas of Francois Bouch- er, a lifelong Venus fan. Venus was also loose. She was occasionally portrayed with her husband, Vulcan (suitably bored in Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem's 'Venus and Vulcan' of 1590), but her dramatic adulterous fling with Mars was a much more popular theme, allowing the treat- ment of many moods from the palpitation of seduction to the shock of discovery. Everyone knows the languorous contempt with which Botticelli, in 1483, has the god- dess gaze on the shagged-out, sleeping Mars. Contrast the passion with which

Venus envelops the god of war, still in his armour, in Titian's painting of 1570 (a workshop version is on show in Cologne). In his 'Mars and Venus' of 1550-1555, meanwhile, Tintoretto lends Venus an expression of blank hypocrisy, while a dod- dery Vulcan peeks under the sheets and Mars, recognisable thanks to the helmet on his head, lurks under a table in the back- ground.

Venus could be vulnerable, too, develop- ing a devouring crush on Adonis as the result of a chance graze from Cupid's arrow. Nicolas Poussin in 1626 painted Adonis's death — Venus arrived tragically too late to save him from being killed by a wild boar while hunting — but most artists preferred the theme of .the goddess's seduction of the young man. The beauty of Simon Vouet's 'Venus and Adonis' of 1642, in which the face of the goddess is barely visible, resides in the tension between the two bodies — she pulling him bedwards, he propped defiantly up on his spear — and the delightful ambiguity of the expression, half succumbing, half fearful of initiation, on Adonis's very young features. On his feet and ready for off, the Adonis depicted by Veronese in 1561, on the other hand, appears more adult and determined — but his gaze is held helplessly captive by hers, while Cupid, in the background, restrains his hounds.

Such was the popularity of the legend that James l's former minion Lord Buck- ingham and Lady Manners, nothing if not brazen, had themselves portrayed with barely a stitch on by van Dyck as Venus and Adonis in 1620. Given the ways Chris- tianity occults carnal pleasure and death, it is natural that art should have employed Venus to bare those parts of the psyche the Church prefers not to reach. The Wallraf- Richartz Museum houses a permanent array of German Renaissance devotional painting, with enough eye-popping martyr- doms and ligament-ripping Crucifixions to sate the bloodiest of sadists. Walk down- stairs, however, and no fewer than 76 Venuses enfold you like a caress.

Previous page

Previous page