Exhibitions 1

In Trust for the Nation: Paintings from National Trust Houses (National Gallery till March 10)

The great collectors

Leslie Geddes-Brown

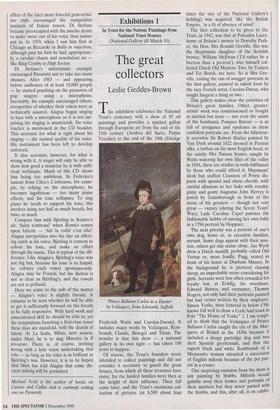

This exhibition celebrates the National Trust's centenary with a show of 95 oil paintings and provides a spirited gallop through European art from the end of the 15th century (Andrea del Sarto, Palma Vecchio) to the end of the 19th (George Prince Baltasar Carlos as a Hunter' by Velcizquez, from Ickworth, Suffolk Frederick Watts and Carolus-Duran). It includes major works by Velazquez, Rem- brandt, Claude, Bruegel and Titian. The wonder is that this show — a national gallery in its own right — has taken 100 years to happen.

Of course, the Trust's founders never intended to collect paintings and did not consider it necessary to guard the great houses, from which all these treasures have come, for the landed families were then at the height of their influence. Their fall came later, and the Trust's enormous col- lection of pictures (at 8,500 about four times the size of the National Gallery's holding) was acquired, like the British Empire, 'in a fit of absence of mind'.

The first collection to be given to the Trust, in 1942, was that at Polesden Lacey, home of Britain's answer to Dorothy Park- er, the Hon. Mrs Ronald Greville. She was the illegitimate daughter of the Scottish brewer, William McEwan (I'd rather be a beeress than a peeress'), who himself col- lected Dutch Old Masters. Two, by Teniers and Ter Borch, are here. So is Mrs Gre- ville, ending the run of swagger portraits in the first gallery, painted in rakish form by the racy French artist, Carolus-Duran, who taught Sargent a thing or two.

This gallery makes clear the priorities of Britain's great families. Other, greater, artists' work was commissioned or bought at auction but none — not even the saints of the bombastic Pompeo Batoni — is as full of arrogance and opulence as these confident portraits are. From the hilarious- ly eccentric Sir Robert Shirley painted by Van Dyck around 1622 dressed in Persian silks, a turban on his most English head, to the saintly Mrs Nassau Senior, caught by Watts watering her own lilies of the valley in 1858, these are studies in wish-fulfilment by those who could afford it. Huysmans' sleek but stuffed Countess of Powis dis- ports with spaniel and obese cherub, with careful allusions to her links with royalty; gamy and gouty Augustus John Hervey is posed by Gainsborough in front of the scene of his greatest — though not very great — victory (during the Seven Years' War); Lady Caroline Capel pursues the fashionable hobby of nursing her own baby in a 1794 portrait by Hoppner.

The next priority was a portrait of one's own dog, horse or, in eccentric families, servant. Some dogs appear with their mas- ters, others get star status alone. Jan Wyck drew a Dutch mastiff, probably called Old Vertue or, more fondly, Pugg, seated in front of his home at Dunham Massey. In the background he is pictured chasing sheep, an improbable scene considering his girth. Servants were less often rewarded for loyalty but, at Erddig, the woodman, Edward Barnes, and carpenter, Thomas Rogers, not only had their portraits painted but bad verses written by their employer, Simon Yorke, were lettered in below (`He knows full well to draw a Cork/And toast in Port "The House of Yorke" '). I am tempt- ed to think that the Velazquez of Prince Baltasar Carlos caught the eye of the Mar- quess of Bristol in the 1830s because it included a sleepy partridge dog and two alert Spanish greyhounds, and that the superb black and white Rembrandt of a Mennonite woman attracted a succession of English milords because of the pet par- rot in a corner.

One surprising omission from the show is any painting by Stubbs. Milords would gamble away their homes and portraits of their mothers but they never parted with the Stubbs, and this, after all, is an exhibi- tion of paintings acquired by private people for their private delight. And delightful it is. The National Gallery's careful and lucid placing of the works, normally viewed as adjuncts of great houses skied up in badly lit corridors, is a revelation. It gives proper importance to the great works, many rarely exhibited and some never, and reveals, for the first time, many small charmers: Bruegel's flying fish skimming above flag irises, nudes with shell and coral cornu- copias, and cheetahs roaming among cab- bages and grapes; George Elgar Hicks's `Dividend Day at the Bank of England' (a neat bow in the direction of the sponsors, Barclays Bank) and Landseer's dashing but tender sketch of the Marchioness of Aber- corn and her baby. In Trust for the Nation: Paintings from National Trust Houses is a show no one should miss and one which everyone will enjoy. Let's not wait another century for a second.

Previous page

Previous page