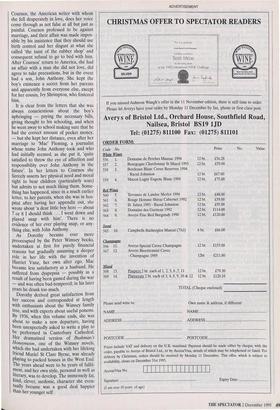

Not so mad about the boy

Isabel Colegate

THE LETTERS OF DOROTHY L. SAYERS, 1899-1936: THE MAKING OF A DETECTIVE NOVELIST edited by Barbara Reynolds Hodder, £25, pp.421 Barbara Reynolds wrote a sympathetic biography of Dorothy L. Sayers which was published in 1993; now she has edited the letters. Previous biographers found Dorothy Sayers a difficult subject — the title of one of the earliest attempts, by Janet Hitchman, is Such a Strange Lady and her letters, read with only the brief linking passages the editor supplies, do not make it easy to like her. She was very clever and she was not very pretty; the two characteristics combined, unfairly enough, to make much of the first half of her life unhappy.

The blurb quotes C. S. Lewis's opinion that Dorothy Sayers would one day be acclaimed as one of the great letter writers of the 20th century; the evidence for this view may appear in the second volume. This one begins with a number of letters home to the parental rectory, from school and from Oxford, whose unremitting jollity probably reflects her genuine enthusiasm for life, but the knowledge that she was far less happy than she pretended — this much the editor's notes do tell us — makes their tone sometimes painfully false. Only in the letters she wrote in her thirties to John Cournos, the American writer with whom she fell desperately in love, does her voice come through as not false at all but just as painful. Cournos professed to be against marriage, and their affair was made impos- sible by his insistence that they should use birth control and her disgust at what she called 'the taint of the rubber shop' and consequent refusal to go to bed with him. After Cournos' return to America, she had an affair with a man she did not love, did agree to take precautions, but in the event had a son, John Anthony. She kept the boy's existence a secret from her parents and apparently from everyone else, except for her cousin, Ivy Shrimpton, who fostered him.

It is clear from the letters that she was always conscientious about the boy's upbringing — paying the necessary bills, giving thought to his schooling, and when he went away to school making sure that he had the correct amount of pocket money, — but she kept her distance, even after her marriage to 'Mac' Fleming, a journalist whose name John Anthony took and who had initially seemed, as she put it, 'quite satisfied to throw the eye of affection and responsibility over John Anthony in the future'. In her letters to Cournos she fiercely asserts her physical need and moral right to bear children (particularly sons) but admits to not much liking them. Some- thing has happened, since in a much earlier letter, to her parents, when she was in hos- pital after having her appendix out, she wrote about 'a dear little boy here — about 7 or 8 I should think . . . I went down and played snap with him'. There is no evidence of her ever playing snap, or any- thing else, with John Anthony.

As Dorothy became ever more preoccupied by the Peter Wimsey books, undertaken at first for purely financial reasons but gradually assuming a deeper role in her life with the invention of Harriet Vane, her own alter ego, Mac became less satisfactory as a husband. He suffered from dyspepsia — possibly as a result of having been gassed during the war — and was often bad-tempered; in his later years he drank too much.

Dorothy derived great satisfaction from her success and corresponded at length with enthusiasts about the Wimsey family tree, and with experts about useful poisons. By 1936, when this volume ends, she was about to make a new departure, having been unexpectedly asked to write a play to be performed in Canterbury Cathedral. Her dramatised version of Bushman's Honeymoon, one of the Wimsey novels, which she had undertaken with her lifelong friend Muriel St Clare Byrne, was already playing to packed houses in the West End. The years ahead were to be years of fulfil- ment, and her own style, personal as well as literary, was to develop. The immensely fat, kind, clever, sardonic, character she even- tually became was a good deal happier than her younger self.

Previous page

Previous page