Apes and Aspers

Roy Kerridge

Only once, at a Spectator lunch, have I ever met the redoubtable Taki, author of the deservedly popular 'High life' col- umn. The door opened and in sauntered a genial, tanned playboy, full of good humour, and, before long, of good wine as well. Everyone brightened up.

'Is that Taki?' I whispered to my neighbour, Simon Courtauld. 'Very,' he replied. (I had pronounced the name 'tacky'.) 'Is it true that you invent your col- umns while doing the washing-up in your parents' Cypriot cafe in Camden Town?' someone, I think Auberon Waugh, asked the great man.

Ignoring these ribbings, the man of the moment sat down and began to praise his hero, John Aspinall, casino owner and zoo- keeper extraordinary. A lively controversy arose, centred on Aspinall' S book, The Best of Friends, and its unusual epilogue, in which the author, concerned for the future of wild animals, calls for a programme of 'abortion, infanticide, euthanasia and birth control' for human beings. Richard West, in his English Journey, extracts a great deal of fun from such passages. Taki defended the book through thick and thin.

Our genial host, Alexander Chancellor, remarked that in his view tigers have no place in Kent. Why did not Aspinall in- troduce wolves instead, which had at one time been native to the region? Chancellor had, I felt, missed the point. Unlike a former Lord Lilford, who had introduced many agreeable wild creatures, such as the Little Owl and sundry ducks, to our shores, Aspinall seeks to keep his animals in cages. Tigers are not at large among the orchards and hopfields, and the tragic deaths of two young keepers took place ,inside the tiger enclosure, which they entered of their own free will. Everyone seemed very interested in Aspinall, and I wondered if I should seize the opportunity to make an official visit to the zoos in Kent, using their owner's fame as an excuse. A connoisseur of zoos, I have visited nearly every such establishment in Britain, but had neglected Kent ever since Sir Garrard Tyrwhitt-Drake closed his menagerie at Maidstone. Proprietors of zoos interest me rather less than the animals. However, I broke off the conver- sation to throw a crusty roll across the table at a girl who had got sozzled and was stuff- ing a bunch of grapes into her handbag. So the moment passed.

Now that the negligence charge against Aspinall is at last being heard in court, his zoos in Kent, Howletts and Port Lympne, may once more be in the news. The time seemed ripe for a visit to Kent, and I bought a railway ticket for Bekesbourne, near Canterbury and half a mile from Howletts Zoo. What is done is done, and I do not propose to reopen old tiger cages. Aspinall's life has been shattered by the event, and he has raised a memorial in his grounds to the two young men. My purpose was to admire the many rare wild animals that John Aspinall has bred in captivity for the first time. Unfortunately, this purpose was not made clear to Aspinall who was rather concerned when he saw me. 'I hope you're not going to do a hatchet job,' he remarked. `No, no,' I reassured him. 'Tell me about your clouded leopards.'

Aspinall has enjoyed considerable suc- cess in breeding rare members of the cat tribe, and soon we were chatting away about his servals, caracals, golden cats, jungle cats, marbled cats, leopard cats, snow leopards and Siberian lynxes. Lunch at Howletts was an agreeable occasion, as I urged my host, a big, bushy-eyebrowed man, muscular from many a playfight with his gorillas, to tell me more and more animal stories. His young son Bassa was more interested in fish, and dreamed of an aquarium with great white sharks. One of my own boyhood dreams, for I once valued wild animals far above mere humans, was to enclose vast areas of Britain, plant oak forests and reintroduce bears, wolves, wild boars, elk, beavers and the rest of it. Sometimes I would also include Ancient Britons, though where I would get them from remained a matter of doubt. Aspinall understood such ambitions all too well.

Mrs Aspinall, all the while, had been looking at the pair of us in silent wonder- ment. Finally, with some diffidence, she asked me if I would mention a flower shop she was opening in Belgravia, Curzon Lawrence Flowers in Motcomb Street. No sooner said than done. With that, John Aspinall and I left the elegant Palladian mansion, with its soft pastel colours and

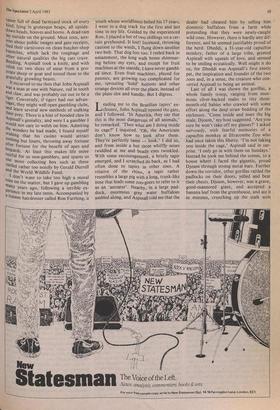

'It's how I see a phallic symbol.'

rooms full of animal paintings and bronzes, and strolled out into the park.

No zoo I had seen compared with this, with bell-shaped cages towering among the trees, giving the animals, whether of cat or monkey tribe, ample room to leap among the branches. Every now and then, Aspinall would break into animal language, crying 'Yip yip!' or uttering a coughing roar, corn- ments which attracting replies in kind from all over the woods. Lacking for nothing, Aspinall's charges were fed with mangoes, avocadoes, grapefruit, lychees and other hothouse fruit, and seemed to enjoy it very. much. Several cages were set at a distance from the public gaze, to ensure privacy f°r the occupants and so encourage their love life, or 'bonding' as the practical Aspinall called it. 'This is the only zoo that is not financed by the public,' Aspinall, who has a healthy disregard for democracy, told nle. 'The animals take first place, and the zoo is run for their sake, paid for by the profits from my casino.' Unashamed of this source of inconte, Aspinall 'related anecdotes about the African chiefs and kings who come to gaol' ble at his club, accompanied by retinues in bright tribal robes. From such experiences he has come to understand the African character, with its many tribal differences, very well indeed. We united in cursing tile African nationalists and politicians wh°se 'independence' movements have alwaYs seemed to me to be fuelled by the desire to abolish Africa altogether and replace it bY a cross between Slough and post-war Moscow. 'Pah! What do you want to see gorillas and such backwardness for?' a Wes,1 African Minister for Forests had exclairneu to Aspinall in disgust. 'Why don't You g° and look at our new Russian-built concrete docks?' Ignoring this advice, the intrepid Aspinall had penetrated the deep rain forests of the interior, and seen a family troop of gorillasi a tiny baby climbing up the brawny arm the great male leader, to ride away on tile patriarch's silver-grizzled back. 'The world is growing unsafe fSri travellers,' Aspinall sighed, thinking of the animals he might never see. 'Piracy ha' returned to the Timor Sea, and in Burrn,,a government writ runs no further than 14 miles from the capital. If you want to go in- to the forest, you have to ask for soldiers,to protect you from guerrillas and dacoits. Wasting no tears for the loss of emPires' Aspinall vaulted into the elephant paddoc'; and began a vigorous game of tag with,0 mischievous youngster, who kept trying _ trip -him up with its trunk. Spectators gathered, as Aspinall played boisteroul with his unique breeding herd of Africarie giants. Charging, butting and frisking, ta baby elephant seemed to be enjoying itsei.

as much as was Aspinall. • all

'I go in with all these tigers,' Aspin _ told me, when we reached a row of lar_g enclosures with pacing, tawny inmates. led me to a bloodstained cold storage con- tallier full of dead farmyard stock of every kind, lying in grotesque heaps, all upside- down heads, hooves and horns. A dead ram !ay outside on the ground. Most zoos, anx- ious about public images and gate receipts, feed their carnivores on clean butcher-shop haunches, which lack the roughage and Other natural qualities the big cats crave. Bending, Aspinall took a knife, and with relish cut two slices of meat from a pro- strate sheep or goat and tossed them to the gratefully growling beasts. It occurred to me then that John Aspinall Was a man at one with Nature, red in tooth and claw, and was probably cut out to be a tiger. Conversely, if tigers had our advan- tages, they might well open gambling clubs, and learn several new methods of stalking their prey. There is a hint of hooded claw in AsPinall's geniality, and were I a gambler I Would not care to welsh on him. Admiring the wonders he had made, I found myself Wishing that his casino would attract nothing but losers, throwing away fortune after fortune for the benefit of apes and leopards. At least this makes life more restful for is non-gamblers, and spares us °Ile more collecting box such as those rattled rather too noisily by Gerald Durrell and the World Wildlife Fund. I don't want to take too high a moral tene on the matter, but F gave up gambling

any Years ago, following a terrible ex- Perience in my late teens. Accompanied by a trainee hairdresser called Ron Farthing, a youth whose worldliness belied his 17 years, I went to a dog track for the first and last time in my life. Guided by the experienced Ron, I placed a bet of two shillings on a cer- tain greyhound. It lost! Incensed, throwing caution to the winds, I flung down another two bob. That dog lost too. I reeled back in amazement, the long walk home shimmer- ing before my eyes, and except for fruit machines at the seaside, I have never gambl- ed since. Even fruit machines, played for pennies, are growing too complicated for me, sprouting 'hold' buttons and other strange devices all over the place, instead of the plain slot and handle. But I digress.

Leading me to the Brazilian tapirs' en- closure, John Aspinall opened the gate, and I followed. 'In America, they say that this is the most dangerous of all animals,' he remarked. 'Then what am I doing inside its cage?' I inquired. 'Oh, the Americans don't know how to look after them. They're perfectly tame — look.' I did so, and from inside a hut three whiffly noses twiddled at me and beady eyes twinkled. With some encouragement, a bristly tapir emerged, and I scratched its back, as I had often done to tapirs in other zoos. A relative of the rhino, a tapir rather resembles a large pig with a long, trunk-like nose that leads some zoo-goers to refer to it as an 'anteater'. Nearby, in a large pad- dock, enormous grey water buffaloes ambled along, and Aspinall told me that the

dealer had cheated him by selling him domestic buffaloes from a farm while pretending that they were newly-caught wild ones. However, there is hardly any dif- ference, and he seemed justifiably proud of the herd. Dheddi, a 31-year-old capuchin monkey, father of a large tribe, greeted Aspinall with squeals of love, and seemed to be smiling ecstatically. Well might it do so, for Dheddi was Aspinalrs first exotic pet, the inspiration and founder of the two zoos and, in a sense, the creature who con- verted Aspinall to being an animal. Last of all I was shown the gorillas, a whole family troop, ranging from enor- mous silver-backed males to tiny three- month-old babies who crawled with some effort along the deep straw bedding of the enclosure. 'Come inside and meet the big male, Djoum,' my host suggested. 'Are you sure he won't take off my glasses?' I asked nervously, with fearful memories of a capuchin monkey at Ilfracombe Zoo who had once taken this liberty. 'I'm not taking you inside the cage,' Aspinall said in sur- prise. 'I only go in with them on Sundays.' Instead he took me behind the scenes, to a house where 1 faced the gigantic, proud Djoum through strong metal bars. Further down the corridor, other gorillas rattled the padlocks on their doors, yelled and beat their chests. Djoum, however, was a grave, good-mannered giant, and accepted a banana leaf from the greenhouse, and ate it in minutes, crunching up the stalk with

gusto. 'When we play, he only uses one tenth of his strength,' I was told.

The keeper who had fetched the leaf, a swashbuckling young man who seemed to admire Aspinall, said that the gorilla had been a bit uncertain in its temper since Aspinall had last entered the cage. They concluded that Djoum believed Aspinall to have paid a little too much attention to his favourite wife. Jealousy is not very seemly in a gigantic gorilla, and I hope Djoum gets over this.

Next day I visited Port Lympne, Aspinall's other zoo, where a good job has been done of restoring Sir Philip Sassoon's old house and its terraced gardens. Robert Boutwood, the young manager, drove me through various paddocks, pausing to send slices of white bread soaring through the air to the rhinos and Mongolian wild horses. From a far corner of their windswept field, the whole herd of wild horses galloped towards us, chestnut with white noses and led by a stallion. I was shown a hyena cage, said to be the best in the world, and two striped hyenas emerged from the undergrowth and stared at the rare Moroc- can lions next door, the feathery fringe of hair along their backs raised as if in inquiry. For their part the lions pretended to stalk the water buffaloes across the way. Some friends and relatives of Aspinall, a young jet-set or Landrover-set crowd, took a lion cub out for a walk, and for some time it raced playfully along through the woods beside our car, leaving me happy memories of Aspinall's zoos.

Even if I were a mad axe-man, swinging hatchets at all and sundry, I hope I would spare John Aspinall and his family. His zoos gave me a Kentish weekend of pure delight, and I urge you to visit them.

Previous page

Previous page