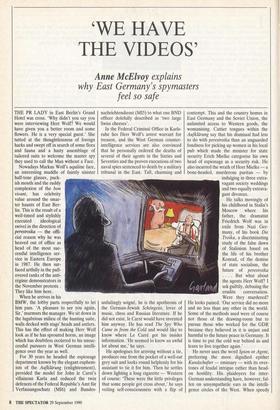

'WE HAVE THE VIDEOS'

Anne McElvoy explains

why East Germany's spymasters feel so safe

THE PR LADY in East Berlin's Grand Hotel was cross. 'Why didn't you say you were interviewing Herr Wolf? We would have given you a better room and some flowers. He is a very special guest.' She tutted at the thoughtlessness of foreign hacks and swept off in search of some flora and fauna and a hasty assemblage of tailored suits to welcome the master spy they used to call the Man without a Face.

executed ideological swivel in the direction of perestroika — the offi- cial reason why he was heaved out of office as head of the most suc- cessful intelligence ser- vice in Eastern Europe in 1987. He then sur- faced artfully in the pull- overed ranks of the anti- regime demonstrators in the November protests. They like him here.

When he arrives in his BMW, the lobby parts respectfully to let him pass. 'A pleasure to see you again, Sir,' murmurs the manager. We sit down in the lugubrious milieu of the hunting suite, walls decked with stags' heads and antlers. This has the effect of making Herr Wolf look as if he has sprouted horns, an image which has doubtless occurred to his unsuc- cessful pursuers in West German intelli- gence over the year as well.

For 30 years he headed the espionage department known by the elegant euphem- ism of the Aufkldrung (enlightenment), provided the model for John le Carre's villainous Karla and reduced the twin defences of the Federal Republic's Amt ffir Verfassungsschutz (MI6) and Bundes- nachrichtendienst (MI5) to what one BND officer dolefully described as 'two large Swiss cheeses'.

In the Federal Criminal Office in Karls- ruhe lies Herr Wolf s arrest warrant for treason, and the West German counter- intelligence services are also convinced that he personally ordered the deaths of several of their agents in the Sixties and Seventies and the proven executions of two naval spies sentenced to death by a military tribunal in the East. Tall, charming and

unfailingly soigné, he is the apotheosis of the German-Jewish Schongeist, lover of music, chess and Russian literature. If he did not exist, le Carre would have invented him anyway. He has read The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and would like to know where Le Carl-6 got his insider information. 'He seemed to know an awful lot about me,' he says.

He apologises for arriving without a tie, produces one from the pocket of a well-cut grey suit and looks round helplessly for his assistant to tie it for him. Then he settles down lighting a long cigarette — Western of course: 'These were the little privileges that some people got cross about,' he says veiling self-consciousness with a flip of contempt. This and the country homes in East Germany and the Soviet Union, the unlimited access to Western goods, the womanising. Cattier tongues within the Aufkliirung say that his dismissal had less to do with perestroika than an unguarded fondness for picking up women in his local pub which made the minister for state security Erich Mielke categorise his own head of espionage as a security risk. He also incurred the wrath of Horr Mielke — a bone-headed, murderous puritan — by indulging in three extra- vagant society weddings and two equally extrava- gant divorces.

He talks movingly of his childhood in Stalin's Moscow where his father, the dramatist Friedrich Wolf was in exile from Nazi Ger- many, of his book Die Troika, a discriminating study of the false dawn of Stalinism based on the life of his brother Konrad, of the demise of state socialism, the future of perestroika . . . . But what about the agents Herr Wolf? I ask guiltily, debasing the erudite conversation.

Were they murdered? He looks pained. 'Our service did no more and no less than any other in the world. Some of the methods used were of course not those of the drawing-room but to pursue those who worked for the GDR because they believed in it is unjust and harmful to the future peace in Germany. It is time to put the cold war behind us and learn to live together again.'

He never uses the word Spion or Agent, preferring the more dignified epithet Kundschafter — emissary — with its over- tones of feudal intrigue rather than head- on hostility. His plaidoyers for inter- German understanding have, however, fal- len on unsympathetic ears in the intelli- gence circles of the West. When speedy unification became a realistic prospect early this year the head of the Hamburg Verfassungsschutz Christian Lochte, an ancient foe of Herr Wolf, delivered an unfraternal message to him and his 4,000 agents in West Germany, 'We will get you all now,' he said. 'Every one of you.'

They won't. For the simple reason that Bonn is avidly hunting for loopholes, excavating exemption clauses and sniffing out the crannies of mitigation to ensure that there is no witch-hunt and very few court cases of any significance to arise after unity from 40 years of German-German treachery. The justice minister Hans En- gelhard fluffed the sleight of hand, howev- er, by announcing precociously that there would be an amnesty for those East Ger- mans who spied 'in good faith' for the Aufkltirung with the exception of those who used 'blackmail, threats or other criminal methods' to gain their ends. This is the prologue to the major farce to be played out of the stage of a unified Germany. How on earth does Herr En- gelhard think that the agents got their information if not by the methods he describes, and how does he intend to sort the venial from the mortal sinners? The government has made it clear that no amnesty will be extended to West German citizens such as the former head of the Verfassungsschutz's vetting department, Hansjoachim Tiedge, who defected to the East, nor to the hundreds of double agents operating in the West for East Berlin. The colour of the spies' passports alone will decide whether or not they risk being clamped in irons. This is probably the only time that the scrawny blue East German identity document has assumed the sym- bolism of freedom over the sturdy green of the West German variety. Or is there now, I wonder, an underground traffic in falsi- fied East German documents reversing the market trend of the past?

Allocation and measurement of moral culpability are not the only problems with this solution: Herr Engelhard has been chastised for playing fast and loose with existing laws according to which all those who spied against West Germany are subject to prosecution regardless of the degree or the motivation for their actions. Flaying promised mercy one week he sent forth his speaker to announce retribution the next. 'Herr Wolf's doorbell and a number of others will very likely ring on the morning of 3 October and steps will be taken against them,' he said. Herr Wolf looks unperturbed at the prospect of an early morning call from the CID: 'I have received certain assurances that the au- thorities in the West subscribe to my way of thinking and that there will not be prosecutions. I cannot imagine any other solution if the social peace is to be pre- served.'

It does not take a decoding machine to realise that Herr Wolf is issuing threats when he talks like this. Over the last months he has unleashed a frenzy of whispers in Bonn ministries by a casual reference to 'a state secretary who is, I would put it like this, rather partial to us', and indicated that if hauled before a court he will tell a long and interesting story about the inner life of West German politics. He is a splendid tease, leaning back in his chair with a twinkle to remark, 'I still like to think I have a few secrets not everyone knows yet.'

Memories of Herr Wolf's major triumph, the infiltration of Willy Brandt's office when he was Chancellor which led to the downfall of Herr Brandt and unnerved the political establishment for the rest of the Seventies, are easily awakened by such talk. Chancellor Kohl also knows that Herr Wolf is not bluffin3: there are still numdr- ous East German agents in positions of influence in Bonn. If he needed any reminding, the CDU's energy spokesman and prominent Hamburg MP Gerd LOffier was arrested earlier this month after a Stasi officer who had jumped ship alleged that the politician had been passing secrets about nuclear and space research to the East for 20 years. Herr Wolf has no comment on the timing or the effect of this revelation.

The threat of political instability already hangs over the new Germany. Better, so goes the reasoning of both CDU and SPD, to forget the pledges to bring to justice the miscreants of the past than to engender a spate of courtroom revelations in the diffi- cult aftermath of unity. This is the 'clean break' view of historical transition which got Germany up and running again after the Third Reich, which eliminates the need for agonies of doubt and recrimination. Despite the promise to arrest Herr Wolf and his minions, it is the view to which almost all of the politically prominent in West Germany subscribe. Less widely publicised than Herr Engelhard's volte- face was a statement by the more reliable public prosecutor Alexander von Stahl that the spies could be arrested after midnight on 2 October but that they would not necessarily be taken into custody. The farce deepens. When is the law not the law? When you can be arrested without even noticing.

This casuistry has the serious side-effect of resting future power in the hands of Herr Wolf together with his less visible successor as head of the Aufklarung, Wer- ner Grossman. They will continue to pull the strings, as Herr Wolf's aide remarked sweetly, 'because we have the videos'. From Interflug hostesses to accommodat- ing ladies lounging in the bars of the Interhotels, the Aufkleirung ran a legion of prostitutes targeted at eminent West Ger- man guests. Then there were the 'Casano- va agents', winsome young men sent to Bonn to woo lonely, middle-aged govern- ment secretaries into passionate affairs and morning-after co-operation. They are said to have totalled 53 major successes with this strategy; many of the women then followed their Casanovas back to East Germany where they are now quaking in their well-furnished apartments. 'Why did so many West German politicians take their holidays in the GDR this year?' runs the latest joke cruising the Bonn cocktail circuit. 'Pure nostalgia. They wanted to see their old secretaries again.' Oh really,' says Herr Wolf, master spy turned dating agency, .!Don't be so censorious. A lot of happy Arriages arose from that little escapade.'

Court cases would be scurrilous but the alternative is a spiral of blackmail, whispering campaigns and distrust. MI5 should pass on the benefit of its experi- ence: it would have been less damaging in ...the long run to know who the Fifth Man was than to have endless speculation on the topic. At least Germany has the choice.

East German spies based in the West employ the time-honoured method of an Einheitsfront— a unified front of silence to protect their identity. It is still functioning admirably and only a conflict of interests such as the natural desire to save one's own skin if it comes to a wave of prosecutions will ever break it. I would not suggest that those who spied for a system they believed in should be imprisoned for the actions that arose from their loyalty, but that they should be strongly encouraged to tell us what they were up to for the last four decades. An honourable amnesty comes after you know what the suspects have done, not before.

The oddest aspect of the twisted tale is that it runs counter to the rest of the unity process. Where Bonn has dictated the political and economic terms of the mer- ger, East Berlin has made the running on what should happen to its spies: nothing. While the precipitous collapse of the GDR provided proof that there was only ever one German nation despite East Germany doggedly avowing the opposite, Bonn is in effect relenting on the legal tenet that all Germans East and West are subject to Federal law. Erich Honecker, who for his 18 years in office was enraged by the refusal of West Germany to recognise East German nationality, has finally seen de facto acceptance of his chimera, the 'social- ist German nation'.

The reason for this belated triumph of the old regime's thinking is that it is beyond rescue and thus beyond reproach. There is no one of note left in East Berlin to be discredited any further than they have already managed perfectly well them- selves without the agitations of a hostile security service. The Federal Republic, on the other hand, now faces the shadows of victory — there are a good number of the great and good whose personal and politic- al peccadilloes are stored in the files and memoirs of East German agents. Already the rumours are spreading. Herr X was always one for the ladies, susceptible to who-knows-what, Minister Y was always chummier than strictly necessary with his East Berlin counterpart. And what of Ostpolitik, the highly praised SPD policy of promoting change in the GDR by inten- sifying contact with its regime? Herr Wolf has already introduced a shadow into the party's romantic view of its recent history by suggesting that the loyalties of Herbert Wehner, the pivotal figure behind both Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt, may have tended eastwards.

With every hesitant doubt planted, every civil sneer which spreads into common currency, Herr Wolf wins a victory. 'I am quite happy to settle down in the new Germany although I have difficulty getting used to the ways of capitalism,' he says. This is rubbish. Markus Wolf has lived beyond capitalism and communism for years in a world of strategy and tribal loyalty. He took three trips to Moscow this year to see his friend Vladimir Kryshkov, head of the KGB, and was rumoured to be transferring East German agents to Mos- cow, including Hansjoachim Tiedge.

This suggestion elicits a look of (I think) scornful pity at the gullibility of the West- ern press. 'The KGB would not touch our agents with a bargepole these days after what has happened in Germany. They wouldn't know which side they were on any more.' This sounds sensible enough. The day after our conversation, however, I heard that Herr Tiedge had apparently fled to Moscow.

Herr Wolf has signed a three-book deal with the publishers Bertelsman for a rumoured 1.5 million marks. He will write

them beautifully and they will tell us very little. We will never really know what he thought it was all for, why he continued in the service of men such as Erich Honecker and the Minister for State Security, Erich Mielke, whose intellect he mocks and whose vision he describes as 'myopic', whether indeed his conversion to peres- troika was any more than an inkling of the way the wind was changing. His agents say they cannot break the habit of calling him by the name he demanded, 'Der Chef' — the boss. He retains more than the title as he leads the nervous new Germany gently and firmly by the nose.

Most of the 4,000 'emissaries' will escape under the terms of whichever amnesty is cobbled together after unity. Anything else would be harsh and dangerous. The major- ity will retire, shaking their heads at the fallibility of historical necessity and confine themselves to taking out their Order of Marx for a nostalgic polish now and then. Others, unable to get used to life without the dead-letter drops and weekly radio messages, will find new paymasters. But there will be a remnant who, like Goethe's Mephistopheles, 'the spirit of all that is negative', will continue quietly to bedevil the united Germany, unleashing scandals, halting careers and sowing discord. For the decade to come they will haunt its institu- tions, a painful reminder of Germany's undeclared civil war, fought on the invisi- ble front.

Anne McElvoy is the Times correspondent in East Berlin.

Previous page

Previous page