My Arnhem orders

William Deedes

Like so many famous battles of the past, Arnhem after 40 years has become a rich field for the 'if only' sort of arugment. There has been a lot of it about this last week. Most of us who were there at the time have something to plant in that field.

In the last desperate hours on Arnhem bridge a bold plan was concocted some- where in XXX Corps which, in deplorably unsuitable territory, was striving to link up with the Airborne. It ran like this: might the battle not yet be turned by securing for a squadron of tanks (with a company of poor bloody infantry riding on the outside of them) a flying start; and then sending them flat out across the crucial gap be- tween leading elements of XXX Corps and Arnhem Bridge?

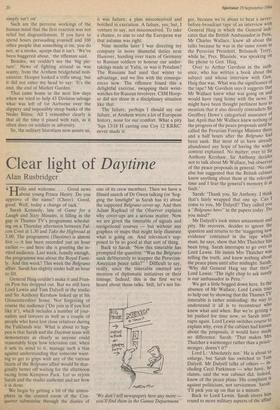

One of the few bits of bumf I carried out of the war and still possess is the Bridge operation order for that bold stroke. I got a copy as company commander of the PBI who were to ride the tanks.

We have set the map a bit. At this stage of the battle (22 September) both Guards Armoured and 43 (Wessex) Divisions, bearing the brunt of the advance of Gen. Horrocks's XXX Corps, were meeting stiff opposition. On the same day Major- General R. E. Urquhart, commanding 1st Airborne at Arnhem, had got a message through XXX Corps stressing the urgency of relief.

We, the 12th KRRC, a motor battalion in 8th Armoured Brigade, had moved to the battle in the wake of the Guards. We had got a place called Dievoort, famous for fruit farmers but not much else. At 11 am on this grey chilly day (22 September) our Brigadier, Errol Prior-Palmer (father of the better-known Lucinda), breezed into our battalion headquarters with the plan. Quite often he flew a cavalry pennant from his armoured scout car. This was missing.

A squadron of 13/18th Hussars, one of our three armoured regiments and the one to which my company was attached, would charge up the road and seize Arnhem Bridge. Like all the best soldiers, the Brigadier had the knack of conveying hazardous operations in sanguine terms. The written orders made it look like a piece of cake.

We were to form up at Elst, about 51/2 miles from Arnhem, and with luck get our flying start from Eldon further up the road and about two miles from Arnhem. True, there was a large factory flanking the road at Eldon (later found to have been stuffed with Germans); but our operation order read airily: 'Probably 300/500 Germans left in Arnhem and factory. Arnhem town and high ground to be smoked throughout.' When the bombers stopped, three field regiments, one medium regiment and a heavy battery would lay down a barrage.

How could we miss? While I was study- ing this inviting prospectus Company Sergeant-Major Hooper sidled towards my armoured half-track. I had acquired CSM Hooper, without much opposition from other company commanders, when my own CSM became a casualty in Normandy.

He was thought to be an indifferent disci- plinarian and was not at all the sort of man to put on Horse Guards for the Queen's

Birthday. But his insolent sang-froid appealed to me strongly. Whether it was

raining rations or rockets or just raining (as it was on this day) CSM Hooper's morose calm reassured.

A successful post-war industrialist owes his life to Hooper. As a junior officer he took out a patrol one night, and did not return. 'Lost his bloody way,' Hooper said unkindly, and mooched casually off into the night with a couple of reluctant rifle- men. He found the future pillar of industry badly wounded on the banks of a Dutch canal and returned him without comment.

Now he approached me with the air of one who had already got wind of Errol Prior-Palmer's slice of cake. 'Bit of a rum do,' he said. It was the nearest he ever got to an expression of alarm.

By then I had reached aerial photo- graphs, vertical and oblique, of our road to Arnhem. The Brigade 10 had thoughtfully marked features of interest en route with white crayon. 'At least, for once,' I said, 'we can see where we're going.' Someone observed, unhelpfully, that a photograph of a factory from the air tells you very little about who are inside it.

We examined the order. 'Speed: flat out from the "off'.' Cavalryman's touch there.

I pointed out that to give us such a start the Household Cavalry armoured cars would secure the start line; no 'off till they did.

For the rest of that long day we re- mained under starter's orders. Then: 'No move before first light.' Some of the riflemen used the interval to write letters home. Absurd details preoccupied me. The op. order said we were to leave our own half track vehicles at Elst station.

How were we to get back to them after riding on the tanks into Arnhem? That sort of.commuter problem whetted CSM Hoop- er's appetite. Not a good night. Had we then known what all the world knows now about the military state of affairs around the Nijmegen-Arnhem road, we could safely have climbed into pyjamas and overslept. It was well into 23 September before the state of battle com- pelled even the most sanguine to let it be known in the language of those days that 'it simply isn't on'.

Such are the perverse workings of the human mind that the first reaction was not relief but disgruntlement. If you have to spend hours persuading yourself and 160 other people that something is on, you do not, at a stroke, accept that it isn't. 'We've been buggered about,' the rifleman said.

Besides, we couldn't see the 'big pic- ture'. News of fighting around us was scanty, from the Arnhem bridgehead non- existent. Hooper looked a trifle smug, but it did not enter my head to say: It's the end, the end of Market Garden.'

That came home in the next few days when we tried to help 43 Division salvage what was left of 1st Airborne over the slippery and impossibly steep banks of the Neder Rhine. All I remember clearly is that all the time it pissed with rain, as it often does on soldiers in adversity.

So, the military historians now assure us, it was failure; a plan misconceived and botched in execution. A failure, yes; but, I venture to say, not misconceived. To take a chance, to aim to end the European war that autumn was right.

Nine months later I was directing my company in more shameful duties near Hanover, handing over tracts of Germany to Russian soldiers to honour our under- takings made at Yalta, or was it Potsdam? The Russians had used that winter to advantage, and we live with the consequ- ences now. The riflemen found this a delightful exercise, swapping their wrist- watches for Russian revolvers. CSM Hoop- er did not shine in a disciplinary situation like that.

The failure, perhaps I should say our failure, at Arnhem wrote a lot of European history, none for our comfort. What a pity `Sqn 13/18 H carring one Coy 12 KRRC' never made it.

Previous page

Previous page