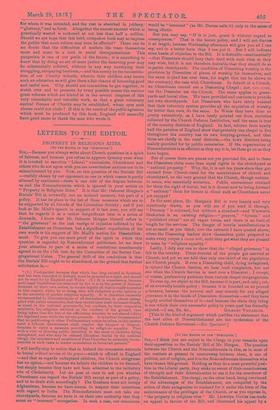

[TO THE EDITOR OF THE "SPECTATOR:]

SIR,—I think you are unjust to the Clergy in your remarks upon their opposition to the Burials' Bill of Mr. Morgan. The question between the Church and the Nonconformists in this, as in most of the matters at present in controversy between them, is one of politics, not of religion, and it is the Nonconformists themselves who have chosen this ground. Holding as they do a most powerful posi- tion in the Liberal party, they make no secret of their consciousness of strength and their determination to use it for the overthrow of the Establishment. The clergy, on the other hand, being convinced of the advantages of the Establishment, are compelled by the action of their antagonists to contend for it under the form of the maintenance of the privileges of the Church, or as you express it, "the property in religions rites." Mr. Llewelyn Davies has made an appeal in favour of the Bill, and illustrated his appeal by a

touching instance of possible hardship under the existing law. The correspondents of the Guardian (of whom I am not one) have appealed to corresponding conceivable instances of gross abuse under the altered law. Both parties are dealing with ideal cases not often likely to occur in practice, but surely the appeal to them is just as allowable on one side as the other.

You say that if the Church could but realise that her religious rites are not a property to be jealously guarded, we should hear a great deal less of the Disestablishment cry. Well, by the same reasoning, if the Nonconformists could be made to feel that their cause was that of Christianity and not Disestablishment, and show their conviction by their treatment of education and other questions, they also would strengthen their position. Does not the whole aspect of affairs show that the time is pad' for such appeals, and that both parties must prepare for action ?

Of the towns I do not presume to speak, my own experience is with the country, and I am confident that the Bill in question would weaken the Church—by this I mean the Established Church—throughout the rural districts. In country parishes— especially scattered parishes—cases of dissent on principle are very rare. Some grievance about a pew,, some squabble with a church functionary, incumbent, or warden, results in a sullen determination not to go inside the Church again, and thus cottage meetings are started, with a preacher from the neighbouring town, and the peasantry near at hand are persuaded to attend, often influenced by the greater distance from the Church, often induced by small and seasonable gifts coming in addi- tion to the regular parish charities and clubs. But there is no feeling, as I say, on principle against the Church. If this Bill were paned, I am confident that the emissaries of Non- conformity would persuade many of these inchoate, unconscious dissenters to insist upon making a display of Dissent, and claiming those rights the absence of which at present they do not feel as a grievance.

Bat you will say that this state of things only proves that in such parishes men are Churchmen as well as Dissenters, because they have not thought about the matter. Let this be granted in many cases—but is not this exactly the meaning of an Establish- ment—that the more ignorant and labouring classes require teach- ing by authority, and this authority is conceded by the State to the Established Church. Dissent should imply deliberate and in- tellectual conviction. Where Dissent is fostered by mere example, or personal feeling, or the defiance of established authority dear to ignorant and untaught minds—where it may be indulged in with safety—then I maintain that Dissent is making progress by un- worthy means, and that it is the duty of the State, so long as it maintains an Established Church, to protect it from injury by

Previous page

Previous page