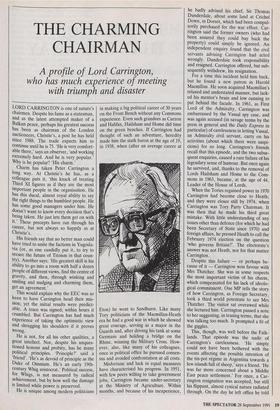

THE CHARMING CHAIRMAN

A profile of Lord Carrington, who has much experience of meeting with triumph and disaster

LORD CARRINGTON is one of nature's chairmen. Despite his fame as a statesman, and as the latest attempted maker of a Balkan peace, perhaps his greatest success has been as chairman of the London auctioneers, Christie's, a post he has held since 1988. The trade expects him to continue until he is 75. 'He is very comfort- able there,' says an observer, 'and working extremely hard. And he is very popular.' Why is he popular? 'His charm.' Charm has taken Peter Carrington a long way. At Christie's he has, as a colleague puts it, 'this knack of treating Third XI figures as if they are the most important people in the organisation. He has this ducal, almost royal ability to say the right things to the humblest people. He has some good managers under him. He doesn't want to know every decision that's being taken. He just lets them get on with it.' These precepts have run through his career, but not always so happily as at Christie's.

His friends say that no better man could have tried to unite the factions in Yugosla- via (or, as one candidly put it, to try to secure the future of Titoism in that coun- try). Another says: 'His greatest skill is his ability to go into a room with half a dozen people of different views, find the centre of gravity, and then, through winking and smiling and nudging and charming them, get an agreement.'

This would explain why the EEC was so keen to have Carrington head their mis- sion; yet the initial results were predict- able. A truce was signed; within hours it crumbled. But Carrington has had much experience of taking the optimistic view and shrugging his shoulders if it proves wrong.

He is not, for all his other qualities, a great intellect. Nor, despite his unques- tioned honour and probity, has he many political principles. 'Principle?' said a `friend'. 'He's as devoid of principle as the Duke of Omnium. He's an early 19th- century Whig aristocrat.' Political success, for Whigs, is not measured by radical achievement, but by how well the damage is limited while power is preserved. He is unique among modern politicians in making a big political career of 30 years on the Front Bench without any Commons experience. Even such grandees as Curzon and Halifax, Hailsham and Home did time on the green benches. If Carrington had thought of such an adventure, heredity made him the sixth baron at the age of 19, in 1938, when (after an average career at Eton) he went to Sandhurst. Like many Tory politicians of the Macmillan-Heath era he had a good war in which he showed great courage, serving as a major in the Guards and, after driving his tank at some Germans and holding a bridge on the Rhine, winning the Military Cross. How- ever, also, like many of his colleagues, once in political office he pursued consen- sus and avoided confrontation at all costs.

Misfortune and luck in equal measures have characterised his progress. In 1951, with few peers willing to take government jobs, Carrington became under-secretary at the Ministry of Agriculture. Within months, and because of his inexperience, he badly advised his chief, Sir Thomas Dunderdale, about some land at Crichel Down, in Dorset, which had been compul- sorily purchased for the war effort. Car- rington said the former owners (who had been assured they could buy back the property) could simply be ignored. An independent enquiry found that the civil servants advising Carrington had acted wrongly. Dunderdale took responsibility and resigned. Carrington offered, but sub- sequently withdrew, his resignation.

For a time this incident held him back, but he found a new patron in Harold Macmillan. He soon acquired Macmillan's relaxed and understated manner, but lack- ed his mentor's brain and low cunning to put behind the facade. In 1961, as First Lord of the Admiralty, Carrington was embarrassed by the Vassal spy case, and was again accused (in savage terms by the press in general and the Daily Express in particular) of carelessness in letting Vassal, an Admiralty civil servant, carry on his activities (about which there were suspi- cions) for so long. Carrington's friends recall that this episode, and the two subse- quent enquiries, caused a rare failure of his legendary sense of humour. But once again he survived, and, thanks to the removal of Lords Hailsham and Home to the Com- mons in 1963, became, at the age of 44, Leader of the House of Lords.

When the Tories regained power in 1970 Carrington had become close to Heath; and they were closer still by 1974, when Carrington was Tory Party Chairman. It was then that he made his third great mistake. With little understanding of any issues other than defence (for which he had been Secretary of State since 1970) and foreign affairs, he pressed Heath to call the February 1974 election on the question `who governs Britain?'. The electorate's answer was not Heath, nor for that matter Carrington.

Despite this failure — or perhaps be- cause of it — Carrington won favour with Mrs Thatcher. She was in some respects the most important victim of his charm, which compensated for his lack of ideolo- gical commitment. One MP tells the story of how Carrington, as Foreign Secretary, took a third world potentate to see Mrs Thatcher. The visitor sat overawed while she lectured him. Carrington passed a note to her suggesting, in teasing terms, that she was talking too much. It prompted a fit of the giggles.

This, though, was well before the Falk- lands. That episode was the nadir of Carrington's carelessness. 'He simply could not have been bothered with the events affecting the possible intention of the tin-pot regime in Argentina towards a few islands full of sheep,' says a friend. 'He was far more concerned about a Middle East peace settlement.' For once, a Car- rington resignation was accepted, but still his flippant, almost cynical nature radiated through. On the day he left office he told

the broadcaster Robert Kee, 'I can stick my tongue out at you now if I like'. He had always embraced irreverence. When meet- ing Dom Mintoff, the Prime Minister of Malta, as Defence Secretary he slightly spoiled a superb diplomatic offensive by being overheard to say of him to a col- league, 'Shocking little man, isn't he?'.

Carrington's uncanny luck soon re- turned. In 1984 he became Secretary General of Nato, his stewardship eased by the beginning of the liberalisation of the Soviet bloc. Even in this great job, he stayed relaxed. At a meeting with a Fore- ign Office minister just before he retired, he signalled that serious business was over by taking the minister by the arm and saying, 'Now, dear boy, don't forget, when you want to sell those heirlooms, be sure you bring them to Christie's.'

The Yugoslavian job is a rare function in Carrington's otherwise enjoyable and ful- filling Indian summer; perhaps another was the outraged rejection of him by the Unionists as the British Government's idea of a chairman of the latest round of Irish peace talks. Honours, notably the Garter, were heaped upon him after his unfortun- ate departure from British politics.

Many great men who do everything right do not end up half so distinguished, cele- brated and rewarded as one who has done more than his fair share of getting things wrong.

Previous page

Previous page