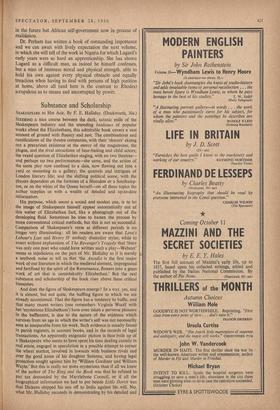

Substance and Scholarship

SHAKESPEARE IN HIS AGE. By F. E. Halliday. (Duckworth, 30s.) STEERING a nice course between the dark, satanic mills of the Shakespeare industry and the unending bat:limes of popular works about the Elizabethans, this admirable book covers a vast amount of ground with fluency and zest. The combinations and ramifications of the theatre companies, with their 'sharers' ekeing out a precarious existence at the mercy of the magistrates, the plague, and the rival attractions of bear-baiting and child actors; the vexed question of Elizabethan staging, with no two theatres— and perhaps no two performances—the same, and the action of the same play now confined to a dais, now flowing out into a yard or mounting to a gallery; the quarrels and intrigues of London literary life; and the shifting political scene, with the players dependent on the fortunes of a Hunsdon or a Southamp- ton, or on the whim of the Queen herself—on all these topics the author supplies us with a wealth of detailed and up-to-date information.

His purpose, which seems a sound and modest one, is to let the image of Shakespeare himself appear automatically out of this welter of Elizabethan fact, like a photograph out of the developing fluid. Sometimes he tries to hasten the process by more conventional critical methods, but this is not so, successful. Comparison of Shakespeare's verse at different periods is no longer very illuminating: all his readers are aware that Love's Labour's Lost and Henry IV embody dissimilar styles; while to assert without explanation of The Revenger's Tragedy that there was only one poet who could have written such a play—Webster' seems as injudicious on the part of Mr. Halliday as it is merely a textbook noise to tell us that 'the Arcadia is the first major work of our literature in which the medieval element, impregnated and fertilised by the spirit of the Renaissance, flowers into a great work of art that is unmistakably Elizabethan.' But the real substance and scholarship of the book rises above these critical blemishes, And does the figure of Shakespeare emerge? In a way, yes, and It is almost, but not quite, the baffling figure to which we are already accustomed. That the figure has a tendency to baffle, and that many recent writers (one remembers Virginia Woolf with her 'mysterious Elizabethans') have even taken a perverse pleasure in the bafflement, is due to the nature of the evidence which survives from an age in which the writer's self was not necessarily seen as inseparable from his work. Such evidence is usually found in parish registers, in account books, and in the records of legal transactions. An apparently enigmatic picture is thus built up of a Shakespeare who seems to have spent his time dealing cannily in real estate, engaged in speculation in a possible attempt to corner the wheat market, involved in lawsuits with business rivals and over the good name of his daughter Susanna, and having legal protection sought against him by 'William Gardiner and William Wayte.' But this is really no more mysterious than if all we knew of the author of The Ring and the Book was that he refused to Pay tax demanded by the Marylebone Council, or if all the biographical information we had to put beside Little Dorrit was that Dickens shipped his son off to India against his will. No, what Mr. Halliday succeeds in demonstrating by his detailed and

sensible methods is the extraordinary similarity of Elizabethan theatrical life and the personalities engaged in it to the literary life of our own or of any other age.

There is the same Bohemianism, the same mixtures of bril- liance and instability, triumphs, jealousies, failures, sudden extinctions and slow declines. Anyone who thinks that romantic and egocentric literary attitudes are a recent growth should con- sider London in Shakespeare's day. The Paris of Balzac and Baudelaire seems tame beside it. Marlowe, ruthless intellectual and secret agent, despising the popular stage, transforming it, and then dying in a knife fight; Greene, a chronic alcoholic; Dekker, who spent most of his life in a debtors' prison : Peele, a seedy fortune-hunter, squandering the small amount of cash his wife brought him. Most came to a bad end : only Marston, one of the most raffish, is grotesquely reborn as a respectable Hampshire parson and son-in-law of one of James I's chaplains. Only Shake- speare, flanked by his two sterling associates and sharers in the Chamberlain's, Heminge and Condell—themselves firm friends and churchwardens of the same parish—remains like a rock above the torrent, steadfastly dedicated to the pursuit of affluence. Per- haps Shakespeare's contemporaries, perhaps writers in every age, really desire wealth and success, but what is remarkably and indeed uniquely felicitous about the Elizabethan age is that its greatest writer was almost alone in obtaining them.

JOHN BAYLEY

Previous page

Previous page