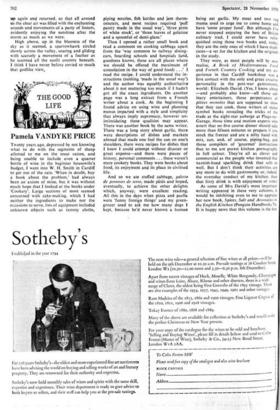

THE GOOD LIFE Pamela VANDYKE PRICE

Twenty years ago, depressed by not knowing what to do with the segments of sheep allotted to me on the meat ration, and being unable to include even a quarter bottle of wine in the beginner housewife's budget, I went into W. H. Smith in Cardiff to get out of the rain. 'When in doubt, buy a book about the problem,' had always been an axiom of mine, but it was without much hope that I looked at the books under 'Cookery'. Large sections of most seemed concerned with cake-making, which I had neither the ingredients to make nor the occasions to serve, lists of equipment included unknown objects such as tammy cloths, piping nozzles, fish kettles and jam therm- ometers, and most recipes required 'puff pastry made in the usual way', 'three pints of white stock', or 'three leaves of gelatine and a spoonful of demi-glaze.'

Then I opened a rather small book and read a comment on cooking cabbage apart from the 'way common to railway dining- cars, boarding schools and hospitals (and, goodness knows, these are all places where we should be offered the maximum of consolation in the way of good food) .. I read the recipe. I could understand the in- structions (nothing 'made in the usual way') and the author was equably authoritative about it not mattering too much if I hadn't got all the exact ingredients. On another page was a long extract from a French writer about a cook. At the beginning I found advice on using wine and planning menus imparted with a style and simplicity that always imply supremacy, however un- intimidating these qualities may appear. There was another book by the same writer. There was a long story about garlic, there were descriptions of dishes and markets abroad that made one feel the sun on one's shoulders, there were recipes for dishes that I knew I could attempt without disaster or great expense—and there were pieces of history, personal comments ... these weren't mere cookery books. They were books about food, its enjoyment and its place in civilised life.

And so we ate stuffed cabbage, galette de pommes de terre, made pâtés and hoped, eventually, to achieve the other delights which, anyway, were excellent reading. All this in the days when pizza and paella were 'funny foreign things' and my green- grocer used to ask me how many dogs I kept, because he'd never known a human being eat garlic. My meat and two veg mama used to urge me to come home and have 'some proper food'. But although I've never stopped enjoying the best of British culinary trad, I could never have refill. quished using those two books and, today, they are the only ones of which I have dupli- cates—a set for the kitchen and the originals in the study.

They were, as most people will by now realise, A Book of Mediterranean Food and French Country Cooking and my ex• perience in that Cardiff bookshop was a first contact with the only and great creative personality in the post-war gastronomic world: Elizabeth David. (Yes, I know about —and probably also know—all those cul. inary entertainers, those perpetrators of pikes monties that are supposed to show that they can cook, those writers of status symbol books revealing the tricks of the trade at the eight-star auberge at Plage-sur- Garage, those time and motion experts who assert that no five course dinner should take more than fifteen minutes to prepare if you stock the freezer and are a nifty hand with mix, can, and, of course, piping-bag, and those compilers of 'gourmet' instructions that to me are purest kitchen pornography in full colour. They're all as clever and commercial as the _people who invented that varnish-hued sparkling drink that sells so well. But I don't think their activities are any more to do with gastronomy or, indeed, the everyday conduct of my kitchen, than that fizzy drink is with enjoyment of wine.)

As some of Mrs David's most important writing appeared in these very columns, it would be inhibiting even to me to appraise her new book, Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen (Penguin Handbooks 7s). It is happy news that this volume is the first

of a series on English cooking. Some of those earlier SPECTATOR articles are quoted; also others which I have torn frem other .pub- lications and wedged into the beats of French Provincial Cooking, Summer Cook- ing or Italian FOod. 4s I intend to send the new Penguin to favoured friends for Christ- mas. I hesitate to reveal all its delights, but m it you will learn -who invented the-kipper, the exact difference between a risotto and a pilau and the dish from which kedgeree was evolved, when Parson Woodforde ate mac- aroni, how to make salted almonds and what happened when the author cooked Christmas pudding in the Mediterranean. The most valuable thing, however, about this, as about all Mrs David's books, is that in using it you become more accomplished in dealing with food, not merely in turning out a particular dish. In reading it you have fun and, afterwards, you certainly will be a more civilised and interesting person. Isn't that, really, what gastronotty should achieve?

Three food and drink anthologies would make good 'When in doubt' presents to have in reserve or to offer to a not as yet well known host or hostess. Olof Wijk's com- pilation Eat at Pleasure, Drink by Measure (Constable 35s) is assembled from the reg- ular bulletins of Christopher's, providing topical comments, recipes (some by Elizabeth David, .Robin McDouall, Prudence Leith, Leslie Hoare, and even by me) and wine notes, all most elegantly arranged. Wine Mine, a first anthology, edited by Anthony Hogg, with a foreword by the late Andre Simon (Souvenir Press 42s) is also very well designed and contains a mixture of fact, gossip (Peter Dominic in-talk of a pleasantly frivolous kind) and accounts of travel in wine regions. The Compleat Imbiber, edited by Cyril Ray (Hutchinson .50s) has now reached volume eleven and is as. handsome and varied a production as ever,

Previous page

Previous page