Dance

Ondine (Covent Garden)

Beauty without tunes

Deirdre McMahon

The revival of Frederick Ashton's Ondine after an absence of 22 years is a cause for celebration. Yet I thought I detected a certain wariness in Ashton's tribute to Anthony Dowell in the program- me, thanking him for 'persuading' him to agree to the revival after such a long time.

Why was Ashton so reluctant to revive Ondine? The ballet disappeared from the repertory when Fonteyn, who created the title role, no longer danced it. But having seen this revival several times I can appreciate Ashton's misgivings. Ondine is a key work in the Ashton canon but it is also a deeply flawed one. The first major problem is the structure. A fey, delicate story is stretched out over three acts and the plot, along with the characters, be- comes submerged. I can think of few other Ashton ballets that have such a weak narrative. Still, Ashton has worked won- ders before with unpromising material. Ondine's problems are, however, magni- fied by the music.

The score was specially commissioned from Hans Werner Henze. Henze admired Ashton's work and probably seemed a good choice. Ashton's musical tastes have been described, unfairly, as unsophisti- cated. He has created memorable ballets to Ravel and Stravinsky but he responds most sensitively to 19th-century music. The more trivial the music, for example Herold or Messager, the more poetic is Ashton's inspiration. Ashton is said to have asked anxiously whether Henze's score had any tunes'. Unfortunately for Ashton, it didn't.

My ear wasn't attacked by the music but neither was it very interested by it. It has some of the jagged quality of Prokofiev's Cinderella, Ashton's first full-length ballet, but unlike Cinderella has no decent music for the pas de deux, always a central metaphor in Ashton's work. Ondine has no strong melodic line for Ashton to get his teeth into and the score is devoid of dance momentum. The Act 3 divertissement is a case in point, busy and over-long. Ashton pummels the music into some sort of dance shape but there is a continual disjunction between eye and ear. For most of Ondine Ashton and Henze seem to be trying to wrestle each other to the mat. Ashton is an innately musical choreographer. Giving him an unsympathetic score is like filling up a Rolls-Royce with vinegar.

But there are parts of the ballet where Ashton triumphs over the score. In Act 1 scene 2, one sees the clear germination of that later masterpiece The Dream. It opens with Tirrenio standing high above the stage in the forest, much as Oberon does, and Tirrenio's solo has signature steps which Ashton was to use in The Dream. Ondine reveals other influences of its time (1958). It was only four years since the first Sadlers Wells production of The Firebird, and the scene where Ondine tries to escape from Palemon in Act 1 has strong echoes of the similar incident between the Firebird and Ivan. But Ondine was also the first major ballet Ashton made after the Bolshoi's visit to London in 1956. The final pas de deux, where Ondine tries to avoid Palemon's fatal kiss, is in a more emotional vein and presages some of the great Ashton pas de deux of the Sixties.

Ashton learned from Ondine. He never made another three-act ballet nor did he work again to a commissioned score. It was also virtually his last hymn to Fonteyn and after Ondine he began to work with other, younger members of the company. It was an end but also the beginning of an extraordinary rich phase in Ashton's career.

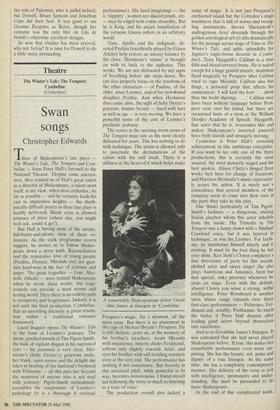

Fonteyn is etched on every step of Ondine's choreography. Her pure, serene line and elegant feet are displayed in Ashton's lavish use of arabesque which becomes part of the iconography of the ballet. I don't set up a wailing dirge for Fonteyn every time one of her big roles is revived. Maria Almeida, who was first cast in this revival, got better and better at each performance, but I was very bothered by her feet, especially since the choreography does so much to highlight them. Almeida has, or used to have, pretty feet, slender and arched. She now wears heavily block- ed shoes that make her feet look stubby and square-toed. This ruins the line of an arabesque and there is a photograph of Almeida in the programme which ungal- lantly exposes this. I know of few other companies where the ballerinas are so badly shod as the Royal and one can see the effect of this in Ashton's choreography. The heavy, clomping shoes rob it of its delicacy and finish.

Cynthia Harvey was not ideal casting as Ondine but her dancing was thoughtful and legible. There is nothing to be done with the role of Palemon, who is pallid indeed, but Dowell, Bruce Sansom and Jonathan Cope did their best. It was good to see Deanne Bergsma as Berta, though her costume was the only blot on Lila de Nobili's otherwise excellent designs.

So now that Ondine has been revived, why not Sylvia? It is time for Dowell to do a little more persuading.

Previous page

Previous page