ARTS T he Manchester International Festival of Expressionism, the first of

its kind to be

dedicated to a single artistic movement, has lasted for three weeks, but at the Whit- worth and the City Art Galleries the exhi- bitions remain as a longer-lived echo to the slow fading of the music and drama.

At the Whitworth, the Austrian compos- er Arnold Schoenberg is an obsessive pres- ence in a group of more than 30 self- portraits, and further works including livid landscapes and portraits of his friends. This is Schoenberg with the sound turned off, an aspect of the inventor of the 12-tone scale that has not been seen before in this coun- try. Looking back hard at his own high- domed forehead, receding hair and drilling eyes, Schoenberg is an unnerving compan- ion in this exhibition. He repeats the full- face composition again and again and again, varying only the angle of lift of the eyes and his medium and painterly tech- nique. If he had ever thought of doing so, this is how Andy Warhol might have paint- ed his shrink.

At times, Schoenberg's stare becomes too strong even for him, prompting his head to dissolve until only the high brow or disembodied eyes remain to float about as if in a pickle jar. Some of these paintings, where the eyes remain and the face fades away, are Schoenberg's Gazes, works which, he said, 'only I could have done ... the work of somebody who never saw faces'. It is the gaze, not the face, that Schoenberg puts down in paint.

Schoenberg's most creative period as a painter was the five or six years between 1908 and 1911, his phase of 'unlimited anarchy and liberty', when he also developed his half-speaking, half-singing technique known as Sprechgesang (speech-song). He wrote later that painting was the same to him as making music. 'It was a way of expressing myself, of presenting emo- tions, ideas and other feelings, and this is perhaps the way to understand these paintings — or not to understand them.'

It is possible that Schoenberg did not fully understand the self-portraits himself, so raw are they in their being, so untainted by any trace of art history or tradition. They are passionate and primitive, though not with the obvious, African primitivism of Schoenberg's artist contemporaries; rather they are expressive of the paranoia of the ground- down clerk or hausfrau, who otherwise fes- ters in a strait-laced society. These self-portraits, however, seem to demand to be taken note of, as part not merely of the

Exhibitions 1

Arnold Schoenberg: Paintings and Drawings (Whitworth Art Gallery, till 9 May) The Expressionist Face (City Art Gallery, till 4 May)

They won't stop misbehaving

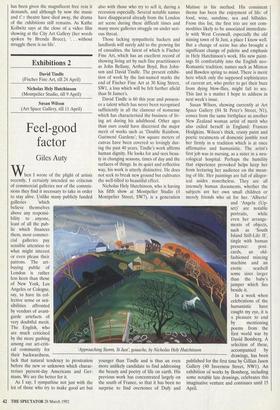

James Hamilton A tendency to melt-down: 'Critic 1', by Arnold Schoenberg history of art, but of the wider history of expression.

Where the face in Schoenberg's portraits shows a tendency to melt-down, the images in Oskar Kokoschka's prints, also at the Whitworth, seem to explode from the cen- tre like grenades. In, for example, the 12 lithographs Columbus Bound (1913), form and dramatic narrative emerge despite the urgent tremor of the hand that holds the crayon and creates the shattering drawing technique. Columbus Bound was produced at the height of Kokoschka's affair with Gustav Mahler's widow Alma, and her presence, like that of a pale, determined, rock-jawed ghost, haunts the series as she herself haunted the artist. On Kokoschka's departure for war in 1915, Alma ended the affair, and when an enemy bullet and bayo- net failed to do their work on him, Kokoschka determined to end his life him- self. He was, however, talked out of suicide and cured of depression, and in the course of time began a new, long life during which he made his corpus of intimate and humane portraits, a heartfelt sigh of relief made visible.

At the City Art Gallery, hung against puce walls, is The Expressionist Face, a superb exhibition of over 80 German prints made from 1905 to 1925. Where the Whit- worth's exhibitions look at the lives and minds of two giants of the century, the City Art Gallery presents the Expres- sionist movement in full flood as it took hold of artists such as Heckel, Schmidt-Rottluff, Barlach and Koll- witz, and crashed upon the sober bourgeoisie of Dresden, Berlin and Munich.

The artists' most favoured medium was the woodcut, a means of expres- sion that gives a punch in the face like none other. With knifes and gouges the image is clawed out of the surface of the woodblock, much as a man trapped in a wooden crate might claw his way out from inside. The medium is cheap and, having only a distant or dismissible art history (Diirer and Holbein disseminated their images through the woodcut), was a splendid way of getting up the noses of the con- noisseurs of fine art. The distortions are still shocking today — heads like breaking eggs, curves colliding in face and body as knowledge of the newly revealed primitive sculpture of Africa and the South Seas was thrown into the crowded salons like a stink-bomb. Expressionist prints will never be quiet, will never stop misbehaving and making a scene.

Expressionism cut uncontrollably across all the generally accepted art bound- aries. This was the nature of the beast.

Composers became painters; painters became dramatists; dramatists such as Fritz Lang and Murnau became film directors. In Manchester this whole unholy boiling has been given the magnificent free rein it demands, and although by now the music and t!.e theatre have died away, the drama of the exhibitions still remains. As Kathe Kollwitz says at the close of a video film showing at the City Art Gallery (her words spoken by Brenda Bruce), `. . . without struggle there is no life'.

Previous page

Previous page