ARTS

Exhibitions

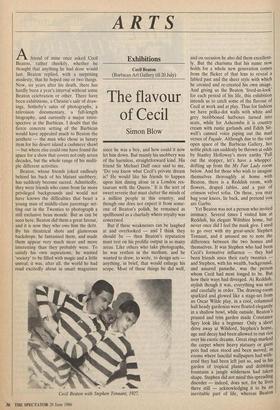

Cecil Beaton (Barbican Art Gallery till 20 July)

The flavour of Cecil

Simon Blow

Afriend of mine once asked Cecil Beaton, rather cheekily, whether he thought that anything he had done would last. Beaton replied, with a surprising modesty, that he hoped one or two things. Now, six years after his death, there has hardly been a year's interval without some Beaton celebration or other. There have been exhibitions, a Christie's sale of draw- ings, Sotheby's sales of photographs, a television documentary, a full-length biography, and currently a major retro- spective at the Barbican. I doubt that the fierce concrete setting of the Barbican would have appealed much to Beaton the aesthete — the man who chose as luxury item for his desert island a cashmere shawl — but where else could one have found the space for a show that covers not only seven decades, but the whole range of his multi- ple different activities.

Beaton, whose friends joked endlessly behind his back of his blatant snobbery, has suddenly become sacred. Admittedly, they were friends who came from far more privileged backgrounds and would not have known the difficulties that beset a young man of middle-class parentage set- ting out in the Twenties to photograph a still exclusive beau monde. But as can be seen here, Beaton did them a great favour, and it is now they who owe him the debt. By his theatrical shots and glamorous backdrops, he fantasised them, and made them appear very much nicer and more interesting than they probably were. To satisfy his own aspirations, he wanted `society' to be filled with magic and a little unreal; it was, after all, the world he had read excitedly about in smart magazines Cecil Beaton with Stephen Tennant, 1927. since he was a boy, and how could it now let him down. But mainly his snobbery was of the harmless, straightforward kind. His friend Sir Michael Duff once said to me, `Do you know what Cecil's private dream is? He would like his friends to happen upon him dining alone in a London res- taurant with the Queen.' It is the sort of sweet reverie that must clutter the minds of a million people in this country, and though one does not expect it from some- one of Beaton's polish, he remained as spellbound as a charlady where royalty was concerned.

But if these weaknesses can be laughed at and overlooked — and I think they should be — then Beaton's reputation must rest on his prolific output in so many areas. Like others who take photographs, he was restless in the medium, and he wanted to draw, to write, to design sets anything, in brief, that would enlarge his scope. Most of these things he did well, and on occasion he also did them excellent- ly. But the charisma that his name now holds for a whole new generation comes from the flicker of that lens to reveal a fabled past and the sheer style with which he created and re-created his own image. And giving us the Beaton 'lived-in-look' for each period of his life, this exhibition intends us to catch some of the flavour of Cecil at work and at play. Thus for fashion we have polka-dot walls with white and grey beribboned hatboxes turned into seats, while for Ashcombe it is country cream with rustic garlands and Edith Sit- well's canned voice piping out the mad verses of Façade. Although due to the vast open space of the Barbican Gallery, her noble pitch can suddenly be thrown at odds by Stanley Holloway's more earthy 'Pull out the stopper, let's have a whopper' drifting up from the My Fair Lady room below. And for those who wish to imagine themselves thoroughly at home with Beaton, there is a Reddish room, with flowers, draped tables, and a pair of crimson velvet sofas. On these, you may hug your knees, lie back, and pretend you are Garbo.

Yet Beaton was not a person who invited intimacy. Several times I visited him at Reddish, his elegant Wiltshire home, but never once did I feel the mask give. I used to go over with my great-uncle Stephen Tennant, and it amused me to note the difference between the two homes and themselves. It was Stephen who had been Cecil's formative influence — they had been friends since their early twenties and Stephen, with his wealth, background, and assured panache, was the person whom Cecil had most longed to be. But how their ways had diverged. At Reddish, stylish though it was, everything was neat and carefully in order. The drawing-room sparkled and glowed like a stage-set from an Oscar Wilde play, in a cool, columned hall heady gardenias were floated elegantly in a shallow bowl, while outside, Beaton's pruned and trim garden made Constance Spry look like a beginner. Only a short drive away at Wilsford, Stephen's home, age and decay had been allowed to run riot over his exotic dreams. Great rings marked the carpet where heavy statuary or giant pots had once stood and been moved, in rooms where fanciful wallpapers had with- ered they had been left just so, and in his garden of tropical plants and dribbling fountains a jungle wilderness had taken shape. Stephen did not mind this spreading disorder — indeed, does not, for he lives there still — acknowledging it to be an inevitable part of life, whereas Beaton would always shudder at the slightest sign of a blemish. And it was Stephen's charac- ter that had grown over the years to be warm and affectionate, and Cecil's distant and reserved.

I say this because Beaton is at his best when pulling a smoke-screen over the truth. His Ascot dresses for My Fair Lady, the society portraits, and that dream crea- tion, Ashcombe, is Beaton relaxed in his happy land of make-believe, but we cannot be fooled when crashed enemy aircraft are taken in the same style. Which reminds me of the last time I visited him with Uncle Stephen. Stephen had under his arm' Noel Coward's plays and he decided to read Cecil a few pages from Design for Living. At one point a character says, 'Nothing is nice.' On this line Stephen paused and turned to Cecil, 'Oh Cecil dear, I think Noel was right — nothing is really nice!' Beaton went quite pale and the lips drew tight. It was, of course, the very last thing he wanted to hear.

Previous page

Previous page