ARTS

Exhibitions

Frances Hodgkins (Whiteford & Hughes till 14 August) Alexis Hunter (Odette Gilbert till 7 August)

Antipodean artists in exile

Giles Auty

Like Henri Matisse, Frances Hodgkins was born in 1869. However, unlike Matisse she was born at the other end of the earth from established European culture, in a remote corner of New Zealand. Had Matisse first seen the light of day at Dunedin rather than at Le Cateau, France, would the history of twentieth century painting have been markedly different? One cannot but suppose so. During 1869 the publisher Lacroix commissioned Emile Zola to write his great series of realist novels. Needless to add, none of these featured everyday life in New Zealand's south island. Dunedin scarcely existed at

all before 1850 and one wonders just how real or unreal life must have seem in this south eastern port, where Antarctica is the next stop, during the latter years of the nineteenth century.

Luckily for Frances her father was, in addition to his daytime career as a solici- tor, a true lover of art and gifted waterco- lourist. Owing to her father's encourage- ment and her own steely determination, Frances was destined to become New Zealand's most important painter. The current large-scale exhibition of her work at Whiteford & Hughes (6, Duke Street, London SW1) is part of. a programme of events which commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Waitangi and the founding of modern New Zealand. Frances Hodgkins remains a great credit to her land of origin.

I was a small child still when I saw a reproduction of Frances Hodgkins's work for the first time. A gouache of a farmyard

scene was illustrated in John Piper's British Romantic Artists, first published in 1942,

and provided one of my first conscious memories of modern painting. Frances Hodgkins trained and taught in New Zea- land and was 32 when she made her first trip to Europe in 1901. Two years later she was the first New Zealander to be hung 'on the line' at the Royal Academy. She travelled to and from her native land twice between that year and the outbreak of the first world war but never returned to the antipodes again, living the life of an often lonely and impoverished artistic exile until the time of her death in 1947.

The artist's life was a more or less unremitting struggle financially, yet this is not reflected in the positive charge of her art. During her years in England, the artist enjoyed the professional friendship of such varied artists as Norman Garstin, Cedric Morris, Charles Ginner, David Jones, Paul Nash and John Piper. While an ardent admirer of Bonnard, Matisse and Picasso, she looked also to the English romantic tradition embodied in the works of Samuel Palmer and John Constable. She absorbed influences and influenced others in turn, yet was always a distinctive voice. I believe the correct way to classify her from the late Thirties onwards is as an integral part of the neo-Romantic movement in England. Her use of still-life in landscape antedated similar subject matter in Ben Nicholson, a member of Unit One. Frances Hodgkins declined Paul Nash's invitation to join that group and also resigned from the 7 and 5

Society when Nicholson steered the group's aim towards abstraction in 1934. John Piper recalls: 'She was a highly intelligent woman, whom I thought was an extremely good painter . . . she was part of us — with no parish, country, climate or anything else attached to her.' Frances Hodgkins's paintings and drawings. are distinguished by a mysterious and haunting beauty. Even ramshackle debris found in the English countryside moved her deeply. 'God never meant New Zealanders to live in London,' she declared. London was seldom kind to her yet celebrates her talent today in galleries and sale-rooms. Half the works in the present show have been borrowed from New Zealand.

Alexis Hunter was born the year after Frances Hodgkins's death at Auckland in New Zealand's other, more northerly is- land. She and her twin sister, artists both, have elected to spend the greater part of their adult lives in London, contrary to God's wishes perhaps. The careers of both suggest they are tougher and more street- wise than the unworldly Frances, posses- sing a pugnacity that is probably wasted on the effete art world. Alexis was formerly held to be a member of feminist move- ments but has switched her interest now to psychic battles within, rather than gender battles without. The present show at Odet- te Gilbert Gallery (5, Cork Street, London W1) is entitled 'Personal Archetypes' and

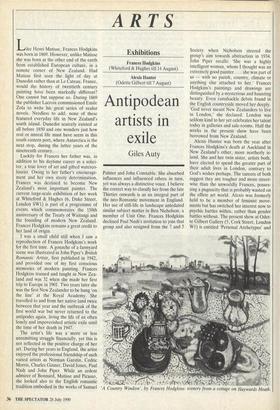

'A Country Window', by Frances Hodgkins: scenery from a cottage on Haywards Heath. features singular symbolic beasts, apparent hybrids of ferret, hyena and kinkajou. These furry fiends have peopled her earlier exhibitions and, for all I know, may be typical inhabitants of the New Zealand psyche. Titles of paintings such, as Letter from Home and Artist as Young Bitch Barking at Her Husband suggest a certain soul-bearing. I cannot help questioning, however, the apparent self-consciousness of this kind of procedure. Was Vermeer secretly afraid of spiders or of his mother- in-law? Throughout 'a lifetime of admiring his paintings I have never sought to know.

Previous page

Previous page