Trade secrets

CHARLES STUART

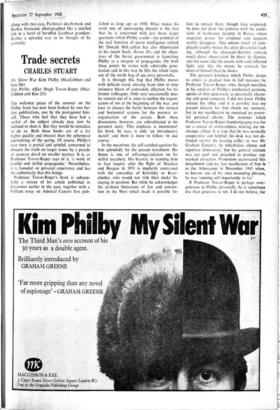

The Philby Affair Hugh Trevor-Roper (Mac- Gibbon and Kee 25s) The welcome peace of the summer on the Philby front has now been broken by two fur- ther publications, one by the protagonist him- self. Those who feel that they have had a surfeit of the subject already may now be inclined to shun it. But they would be mistaken to do so. Both these books are of a far higher quality and interest than the ephemeral journalising of the spring. Of course, Philby's own story is partial and spiteful, concerned to obscure the truth on larger issues by a parade of accurate detail on smaller matters. It is, as Professor Trevor-Roper says of it, `a work of careful and skilful propaganda.' Nevertheless, it is founded on personal experience and has the authenticity that this brings.

Professor Trevor-Roper'i book is substan- tially a reissue of his article published in Encounter earlier in the year, together with a brilliant essay on Admiral Canaris first pub- lished as long ago as 1950. What makes his work one of outstanding interest is the fact that he is concerned with just those larger questions which Philby avoids—the problem of the real function of .secret intelligence (which Mr Donald McLachlan has also illuminated in his recent book, Room 39), and the objec- tives of the Soviet government in launching Philby as a weapon of propaganda. On both these points he writes with admirable pene- tration and in this way he lifts the whole topic out of the sterile bog of spy-story personalia.

It is through this bog that Philby moves with delicate tread, uttering from time to time- insincere bleats of comradely affection for his former colleagues. Only very occasionally does he venture out of it, once to outline the organi- sation of sis at the beginning of the war, and later to discuss the battle between the vertical and horizontal systems for the postwar re- organisation of the service. Both these discussions, however, are subordinated to his personal story. This emphasis is intentional; his book, he says, is only `an introductory sketch' and there is more to follow 'in due course.'

In the meantime, his self-satisfied egotism fits him splendidly for the present instalment. His theme is one of self-congratulation on his skilful treachery. His bravery in standing firm to face inquiry after the flight. of Maclean and Burgess in 1951 is implicitly contrasted with the cowardice of Krivitsky or Krav- chenko, who would not 'risk their necks' by staying in position. But while he acknowledges the civilised limitations of law and conven- tion in the West which made it possible for him to remain there, though long suspected, he does not draw the contrast with the condi- tions of barbarous tyranny in Russia where suspicion passes for evidence and suspects swiftly disappear. This odious touch of com-

placent cruelty makes his story distasteful read- ing, although his character-sketches contain much clever observation. In short, he illumin- ates the scene, like the moon, with cold reflected light, and. like the moon, he conceals far more of himself than he shows.

The personal kindness which Philby denies to others' is granted him in full measure by Professor Trevor-Roper, who, though merciless in his analysis of Philby's intellectual position, speaks of him generously as personally charm- ing and good company. I did not know Philby outside the office and it is possible that my present distaste for him clouds my memory, but in my recollection he exercised no power- ful personal charm. The stammer which Professor Trevor-Roper found engaging was for me a source of awkwardness, making our ex- changes stilted. It is true that he was normally cooperative and helpful; his desk was not de- fended against the passing caller, as was Mr Graham Greene's. by rebarbative silence and repulsive demeanour; but his general attitude was too cool and detached to produce any marked attraction. Promotion accentuated this detachment and my last recollection of him Is -• in the Athenaeum• in November 1945 when, to borrow one of his own wounding phrases, he was `running self-importantly to fat.'

If Professor Trevor-Roper is perhaps over- generous to Philby personally, he is sometimes less than generous to sts. I do not believe, fOr example, that even Colonel Vivian considered Philby to have been in touch with the Germans. The situation which I believe he had in mind was a great deal more Irish than that. Nor do I think that Colonel Cowgill's departure was solely the consequence of Philby's in- trigues. Cowgill sincerely resisted the reorgani- sation of intelligence against the Germans in connection with the war; it was this that built up feeling against him inside and outside sts and which made his removal probable, Philby or no Philby, intrigue or no intrigue.

But these differences of emphasis are of small account. The fascination which Professor Trevor-Roper's book exercises arises from its search for the truth on things that matter, from the characteristic elegance and balance of its construction and from its convincing answers. His analysis of Russian objectives has been amply confirmed by the recent engulfing of Czechoslovakia; his summary of the real func- tion of secret intelligence is lapidary; and his demolition of Mr Le Carre's sociological clap- trap leaves, as Gladstone observed of Purcell's Life of Manning, 'nothing for the Day of Judgment.'

Sadly, he has been unable to take similar judicial notice of Mr Graham Greene's strange introduction to Philby's book apart from one sardonic footnote. For this, though shorter than Mr Le Carre's effort, is no more convincing. Mr Greene's verdict, for example, on the statement that Philby betrayed his country is—`yes, perhaps he did.' His gloss on this extraordinary judgment is no less astonish- ing; 'who among us,' he asks, 'has not com- mitted treason to something or someone more important than a country?' The inconsequence of this is worthy of Mr Wilson at Question Time. At least there is no 'perhaps' about it for Philby. He is a self-confessed traitor and he is proud of it. So Mr Greene's intriguing comparison of his perjury with some seedy individual infidelity will hardly gratify him.

The details of Philby's career are now, as Professor Trevor-Roper concludes, irrelevant. But the Soviet Intelligence Service remains powerful and baleful, as the Czechs are learn- ing. We should not assume that it is any less active among us now than it was thirty or forty years ago. When Philby writes: 'I felt that I knew the enemy well,' he means us and he speaks for the Soviet Intelligence Ser- vice. Let us be on our guard.

Previous page

Previous page