Lost leader

Raymond Keene

In the years since he routed Spassky at Reykjavik in 1972, Bobby Fischer has not played one single competitive game. He feels no real incentive to take part in tournaments since the opposition is not sufficiently challenging, so our hopes of seeing him compete again must lie in the possibility of his playing a match against an outstandingly strong opponent, probably with an enormous sum of money at stake. Now that he has defected from the USSR, and is enjoying the relative security of political asylum in Switzerland, Korchnoi is free to arrange his own playing schedule, and is probably the most likely person to drag Fischer out of hibernation.

Rumours in 1978 of an impending Gligoric-Fischer match amounted to nothing, possibly because Gligoric's hands were tied on certain sensitive issues by his (ultimately unsuccessful) bid for the presidency of FIDE. Since both Korehnoi and Fischer are on bad terms with the World Federation,1 would have thought this might represent a common bond, persuading them to shelve their personal differences and come together in a match. There were already negotiations between the two in 1977, but these were cut short by Korchnoes obligations in the official world championship cycle, which ended with Korchnoi's defeat by Karpov at Baguio.

Fischer's prolonged absence from the chess scene has deprived us of the pleasure of witnessing his universal style of play in action. He, more than any other player in chess history, combines the five classical elements of chess strategy with an almost magical perfection. Of these five elements (material, time, space, pawn structure and king safety) possibly the most important are the last two. Naturally I do not mean that one should sacrifice pieces with abandon, but the element of pawn structure has a permanence which time and space lack, while king safety is of paramount importance, given that mate is the ultimate objective of the game. The positional advantage of superior pawn structure, combined wih the dislocation of the opposing king's surroundings, is often worth an investment of one or two pawns.

In the brevity which follows, Fischer exhibits this blend of themes to perfection. Although Black acquires a couple of extra pawns at an early stage, his position becomes disorganised as a result of the loosening stemming from 2 ... P-KB3 and his subsequent inability to castle. The tactics which exploit these positional factors begin with 13 BxP!, fittingly enough a stroke against the very same dark squares that Black's opening strategy was designed to protect.

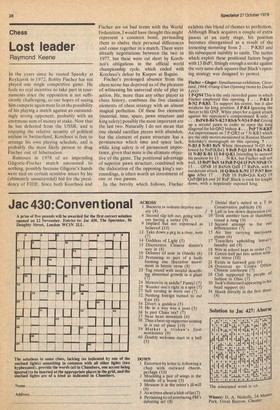

Fischer — Ginger: Simultaneous exhibition, Cleveland, 1964; Orang-Utan Opening (notes by David Levy) 1 P-QN4 This is the only recorded game in which Fischer employed this opening. 1 . . . P-K4 2 B-N2 P-KB3. To support his centre, but it also weakens his king position. 3 P-K4 Ignoring the threat to his QNP, White plays for a quick attack against his opponent's compromised K-side. 3 . . . BxP4 B-B4 N-K25 R5ch N-N3 6 P-84! Giving up a second pawn in order to open the long diagonal for his QN2 bishop. 6. . NP 7 N-KB3I An improvement on 7 P-QR3 or 7 N-KR3 which are the only moves mentioned in Russian Master Sokolsky's monograph on this opening. 7 . . • N-B3 8 N-B3 BxN White threatened N-Q5 followed by blxP(KB4). 9 BxB P-Q3 10 N-R4 N-K2 11 N-B5 K-B1 12 0-0 Q-KI Intending to unravel his position by 13 . , . N-K4, but Fischer will not wait. 13 BxPi BxN 14 NB P-Q4 15 PxN NPxB Or 15 . . QPxB 16 BxNeh QxB 17 RxPch, with a nurderous attack. 16 Q-R6ch K-N1 17 P-N7 Resigns After 17 . „ Px13 18 Px11.•Qch KxQ 19 QxP(B6)ch and 20 RxP, Black is rook for knight down, with a hopelessly exposed king.

Previous page

Previous page