A class act

Sheridan Morley remembers John Gielgud, who died this week aged 96 . . .

The voice on my telephone about five years ago was unmistakably the voice of Hamlet, and faintly accusatory. 'My biogra- pher,' it said, 'seems to have died.'

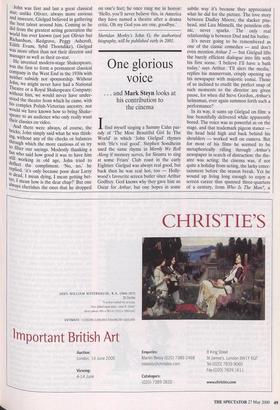

I thought perhaps this was in some vaguely unspecified way my fault. For once it wasn't; the great and good Richard Find- John Gielgud, 1959, photographed by John Hedgecoe, and in his exhibition Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery until 18 June later had indeed died at a reasonable (though not of course by Gielgud stan- dards) age, and John had decided I might make a suitable understudy. In a sort of way I had known him all my life; my grandmother Gladys Cooper had been directed by him in Bagnold's The Chalk Garden, and Robert, my father, by him in Ustinov's Halfway Up a Tree. My now near-90-year-old mother used to hunt in Ireland with his first great love, the play- wright John Perry, at the beginning of the 1930s, before the two Johns ever met. There were curious family connections like this, but nothing very close; the theatre to which my father and grandmother belonged was defiantly anti-classical, and my own relations with John had been limit- ed to countless radio, television and print encounters,. and his help with several of my stage and screen biographies for which he was kind enough to be interviewed at length, write the prefaces and tell me of something or someone I had overlooked. Quite apart from his acting and direct- ing, he was an amazing stage historian; only a couple of years ago he published his own collection of programmes from the London theatre of the first world war, during the latter part of which he was a schoolboy at Westminster. In his own wonderfully spi- dery handwriting, all had, in the margins, detailed reviews of plays and players which any critic would have been proud to deliver today, let alone when we were 14. He came of course from the Terry Pur- ple, as he always said, a family with cur!- ously weak tear glands; Ellen was Ws great-aunt, which meant that John was the bridge from the Irving barnstormers to lat- terday Shakespeareans with the close-111) subtlety of a Derek Jacobi. Every actor, liv ing or dead, in John's century was also in his debt; not just the thousands he worked with as actor, director and manager — he effectively discovered both Alec Guinness and Paul Scofield — but all the others, villa watched him from the wings. Happily we have him with us forever on tape (he and his brother Val virtually invented radio drama in the 1920s) and 4? course on screen. A few weeks ago, on J' 96th birthday in April, he was filming Samuel Beckett drama with Harold Pinter. for David Mamet; when I asked him how ° felt to be working with two great Pla3,7- wrights on such an anniversary, he merelY said, 'Surprising.' All the same, I think he was about ready r to go; his lifelong partner Martin HerisleA had died the Christmas before last, and John was feeling increasingly lonely all'a fragile. When, thanks to Janet Holmes Court, we got the Globe Theatre °,_e Shaftesbury Avenue rechristened so that °.0 would forever have his name up the!'e ble lights, he said to me rather sadly, qt,11 ill such a relief to find there is one name it s recognise.' The trouble with surviving more than nine decades is that most of Y° friends and colleagues don't. John was first and last a great classical star; unlike Olivier, always more envious and insecure, Gielgud believed in gathering the best talent around him. Coming as he did from the greatest acting generation the world has ever known (not just Olivier but Richardson, Redgrave, Peggy Ashcroft, Edith Evans, Sybil Thorndike), Gielgud was more often than not their director and manager as well as their co-star.

He invented modern-stage Shakespeare, was the first to form a permanent classical company in the West End in the 1930s with neither subsidy nor sponsorship. Without John, we might never have had a National Theatre or a Royal Shakespeare Company; without him, we would never have under- stood the theatre from which he came, with his Complex Polish-Victorian ancestry, nor would we have known how to bring Shake- speare to an audience who only really want their classics on video.

Arid there were always, of course, the h ricks; John simply said what he was think- ing, without any of the checks or balances through which the more cautious of us try to filter our sayings. Modestly thanking a fan who said how good it was to have him still working in old age, John tried to deflect the compliment. 'No, no,' he replied, 'it's only because poor dear Larry is dead, I mean dying, I mean getting bet- ter, I mean how is the dear chap?' But one always cherishes the ones that he dropped on one's feet; he once rang me in horror: `Hello, you'll never believe this, in America they have named a theatre after a drama critic, Oh my God you are one, goodbye.'

Sheridan Morley's John G, the authorised biography, will be published early in 2001.

Previous page

Previous page