IF BONDY BEACHES.. .

Robert Haupt looks

at the ailing finances of Alan Bond

THE inhabitants of the Australian south- west are probably the most isolated settlers of the Western world, and at any moment they are at least half-convinced that some- one is conspiring against them. Perhaps it is ever thus in Paradise.

To the 'ten-pound' migrants from post- war England who left the ship at Freman- tle, got a job and put a deposit on a house, Perth offered a life of luxury and opportun- ity unimaginable back home. These mig- rants formed the core of the city's expan- sion into the sandy interior, where they lived in suburbs sewered by septic tanks amid gardens watered from bores — a Confluence which led to an unmistakable tang in the air. The gardens flourished. This was the atmosphere into which, in 1951, stepped an English boy of 13. Alan Bond was born in Ealing, and came to Western Australia because his father, wounded in the war and given only a year to live, was told that the dry heat there might prolong his life. (Perhaps it did: he lived for another 20 years.) The record reads as if it were the son, not the father, who got the death sentence: painter's apprentice (studying accountancy at night) at 14; married at 17; land-owner at 18; property developer at 21; millionaire at 26. Then, you could say, he really stepped on the gas. Today, he owns Australia's most in- fluential commercial television network, its second largest brewery, mines, a major newspaper and a great deal of property. Internationally, he supplies beer to the Mid-West of America, telephones to Chile, office space in Hong Kong and manorial services to the residents of GlYmpton Park, Oxfordshire. His British satellite service is due to begin later this Year.

In 1983, he brought the Americas Cup Yachting trophy to Australia. It is now Possible to see that that was his finest hour. The Prime Minister, Mr Bob Hawke, went on television immediately after the victory and said that any employer who wouldn't give his workers the day off to celebrate was 'a bum'. More to the point, the boy from Ealing was no longer Mi Bond, or even Alan; he had won the greatest honour ordinary Australians confer, a diminutive. He was Bondy.

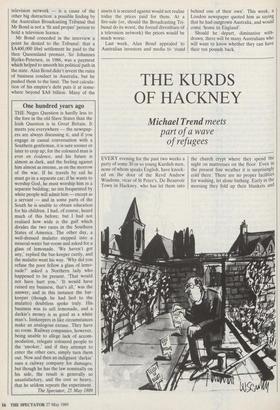

Alan Bond is small, round, ill-read, pugnacious, optimistic and imaginative. In a tight corner, he is a never-surrender man; with something to sell, formidable; in charge of a team, inspiring. So why is he at, headed for or (depending on your source) already beyond the point of going broke?

The answer is more than a cautionary tale for other likely lads from Ealing. It is a caution to lenders such as the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, Midland, Merrill Lynch and various Australian banks. It raises questions concerning accounting and auditing standards. And, like the aroma of a Perth garden in the Fifties, it even has a whiff of corruption.

Alan Bond has been to the brink before. In 1975 and in 1982 his debt-driven growth almost brought him catastrophe. He evaded it through grit and flair — he is a Churchill without the speech function and the benign view of his current difficul- ties that has prevailed until recently derives from those escapes. After all, you have always been able to place a bet by naming the day on which Bondy will go broke.

But the view has now changed. Bondy is becoming Bond again; share prices in his companies have fallen sharply; much atten- tion is given to a missed dividend payment here, an instalment on a coal mine not met there. Once again, bets are being laid on his demise. And it is the same story: too much debt.

Alan Bond didn't so much discover high gearing as take part in its birth. Credit, applied to assets, works like fertiliser on vegetables: you achieve growth on a higher plane. And the lean years? Bond once described them thus to an Australian jour- nalist: 'It takes a long time to go broke.'

Highly-geared companies must grow rapidly to avoid collapsing under the weight of their debt. To Mr Bond, it has never much mattered that he paid over the odds for a particular asset, so long as bankers would lend against it. Growth would eventually cure any mistakes, while the complexity of his group's accounts made it difficult to discover the values being placed on assets in the meantime.

But Bond's acquisition run has stopped. The word he used to a meeting of finan- ciers in Sydney last week was `deconsolida- tion', an entirely foreign noise to hear from him. He is selling down his brewery hold- ings, while a range of other assets, includ- ing the St George's Hospital site in Lon- don, are for sale.

To take the tension out of an over- wound spring is a tricky thing, but that is what Alan Bond must now do if his empire is to become smaller without collapsing. At the same time, he must deal with a couple of aggravating distractions. One watches with fascinated horror, as if a bomb- disposal expert, working on a delicate fuse, were at the same time trying to kick away two terriers gnawing at his ankles.

The first terrier is Tiny Rowland, who retaliated against Mr Bond's unwanted appearance on the Lonrho share register by releasing a blitz of propaganda designed to weaken the Bond empire in the eyes of its creditors and shareholders. The score at the time of writing stands at Rowland five, Bond nil.

Mr Rowland claims that the Bond empire is 'technically insolvent', a claim which, when taken up in the Australian media, leads Mr Bond to wonder aloud whether his adopted home has come to resemble Nazi Germany. The chief effect of the Rowland campaign (apart from putting paid to any chance of Mr Bond taking over Lonrho) has been to encourage detailed and critical examination of the Bond balance sheets. A television documentary raised embarrassing ques- tions about the sale of a property in Rome to a two-dollar company, allowing Mr Bond to book a $A47 million profit last financial year. This sale has since been reversed.

The Australian media — in this case, an interview given by Mr Bond to his own television network — is a cause of the other big distraction: a possible finding by the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal that Mr Bond is not a 'fit and proper' person to hold a television licence.

Mr Bond conceded in the interview a point he denied to the Tribunal: that a $A400,000 libel settlement he paid to the then Queensland premier, Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen, in 1986, was a payment which helped to smooth his political path in the state. Alan Bond didn't invent the rules of business conduct in Australia, but he pushed them to the limit. The best calcula- tion of his empire's debt puts it at some- where beyond $A8 billion. Many of the assets it is secured against would not realise today the prices paid for them. At a fire-sale (or, should the Broadcasting Tri- bunal do its worst, the forced divestiture of a television network) the prices would be much worse.

Last week, Alan Bond appealed to Australian investors and media to 'stand behind one of their own'. This week, a London newspaper quoted him as saying that he had outgrown Australia, and would come 'home to England'.

Should he depart, diminutive with- drawn, there will be many Australians who will want to know whether they can have their ten pounds back.

Previous page

Previous page