Democracy with one voice

Desmond Stewart

Cairo The flight to Jerusalem which made Sadat a World figure at the cost of dividing the Arabs has been paralleled by an internal Initiative — towards pluralistic freedom — Which has divided Sadat himself, and which has recently appeared to be as near its funeral as the movement towards a peaceful settlement with Israel.

Since 1971, when he crushed what he termed 'leftist' centres of power, the EgyPtian president has repeatedly stated his wish to construct a democratic society under the rule of law. To many, this gave kin an advantage over his predecessor; it enabled him to answer despotic Arab critics and it reflected, in fact, a genuine aspect of his complex personality. In apparently moving further than Ataturk — by authorising four parties as against his two — Sadat was reverting to an Egyptian pattern. For, except in its loss of independence, the nineteenth century Pashadom, then hediviate, was at every stage ahead of unPerial Turkey, whether in the introduction of railways, the opening of girls Schools or in the formation of democratic Institutions. Under Ismail (who opened the Canal and was dethroned for debts which would seem trivial today) an Egyptian Jew could run a satirical magazine which caricatured the ruler. Britain's ablest proconsul, Lord Cromer, allowed 'the vernacular press' to rant (as he thought it) and in the Twenties and Thirties Egypt enjoyed n ramshackle democratic system only hinited by its dependence on British approval. Financial, and other scandals gave Nasser his chance to launch a coup d etat which, despite removing Farouk and despite many positive achievements, failed to produce a society which an Egyptian Could oppose with impunity. Thus in attacking Nasser's 'visitors of dawn', police torture, sequestration and the political isolation of individuals, Sadat was attacking known evils. In demanding the rule of law and a democratic system he was not invoking something new or ill-understood. Democracy, on one level, appeals to 4Yptians: their noted humour indicates a Sense of proportion while their ritualised street violence — the Dowsha, in which two inen seem set on mutual murder but are reconciled by onlookers, can be seen today as It was by Florentine visitors in the middle ages — shows a mature awareness that violence must be checked. But there are Shades in the picture. Humorous, tolerant, he Egyptians have been so long oppressed UY rulers, usually foreign, that frankness is 110.t a national characteristic. I remember ueing attacked by a young Egyptian, a few weeks before Farouk's overthrow, for suggesting that his majesty gambled too much. The same student was doubtless shouting pro-Nasser slogans a little later.

As in other Islamic societies, an almost Lutheran acceptance of the ruler qua ruler inhibits criticism. The notion of a loyal opposition has been imported. And Sadat himself has spent so much of his life in an atmosphere of reverence that even mild criticism can appear outrageous. Equally, in a society so tightly corseted the publication of scandals can be explosive. Sadat recently defined democracy as 'the exchange of views through the official channels in a respectful manner.' He has found disrespectful the criticism emerging in the people's assembly and in the two opposition party newspapers representing the right and the left. Members of Parliament and the leftist newspaper Al-A haly have discussed stich controversial projects as the establishment of a geriatric, or plutocratic suburb on desert land near the Pyramids, and the sale of the Egyptian cinema industry to a Saudi financier acting for a group of American companies. An article on 'Family Capitalism' which unravelled the web of enterprises controlled by Osman Ahmed Osman annoyed certain highly placed connections by marriage of Egypt's richest and most • effective tycoon.

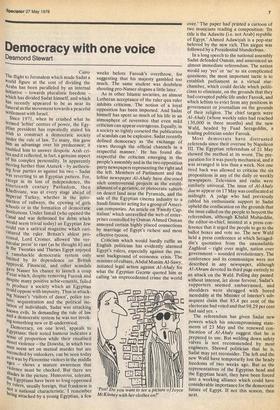

Criticism which would hardly ruffle an English politician has evidently alarmed Egypt's rulers, especially against the pre sent background of economic crisis. The minister of culture, Abdul Munim Al-Sawy, initiated legal action against Al-A haly for what the Egyptian Gazette quoted him as calling 'an unprecedented crime the world over.' The paper had printed a cartoon of two musicians reading a Composition: 'Its title is the Adawite (i.e. not Arab) republic of Egypt.' Ahmed Adawiyah is a pop-star beloved by the new rich. This airgun was followed by a Presidential blunderbuss.

In a long speech to the national assembly Sadat defended Osman, and announced an almost immediate referendum. The nation would say 'yes' or `no' to six complicated questions; the most important tactic is to establish parliament as a virtual starchamber, which could decide which politicians to eliminate, on the grounds that they had corrupted public life under Farouk, and which leftists to evict from any positions in government or journalism on the grounds of their religion. The chief targets were Al-A haly (whose weekly sales had reached 130,000 in three months) and the new Wafd, headed by Fuad Serageddin, a leading politician under Farouk.

Most democrats have distrusted referenda since their overuse by Napoleon III. The Egyptian referendum of 21 May showed the method at its worst. The preparation for it was purely mechanical, and it was arranged in less than a week. Not one tired hack was allowed to criticise the six propositions in any of the daily or weekly newspapers. Television and radio were similarly univocal. The issue of Al-A haly due to appear on 17 May was confiscated at midnight. A judge who had previously cabled his enthusiastic support to Sadat upheld the confiscation on the grounds that the issue called on the people to boycott the referendum, although Khalid Muhieddin, the editor-in-chief, insisted at a press conference that it urged the people to go to the ballot boxes and vote no. The new Wafd held a press conference at which Serageddin's quotation from the unassailable Zaghloul — right over might, nation over government — sounded revolutionary. The conference and its communique were not described in any newspaper, although Al-A hram devoted its third page entirely to an attack on the Wafd. Polling day passed without interest, let alone fervour. Sadat's supporters seemed embarrassed, and shoulders were shrugged with bored incredulity at the Minister of Interior's sub sequent claim that 85.4 per cent of the electorate had voted and that 98.29 per cent had said yes. .

The referendum has given Sadat new powers which his uncompromising statements of 23 May and the renewed confiscation of Al-Ahaly suggest that he is prepared to use. But welding down safety valves is not recommended by most engineers. Shrewd politician that he is, Sadat may yet reconsider. the left and the new Wafd have temporarily lost the heady freedoms of two weeks ago. But as the representatives of the Egyptian head and the Egyptian heart, they have been forced into a working alliance which could have considerable importance for the democratic future of Egypt. If not this season, then next.

Previous page

Previous page