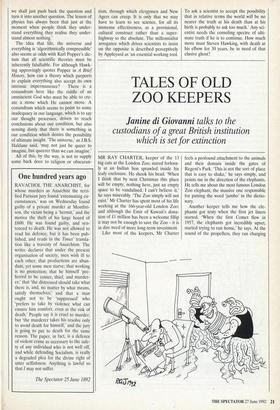

TALES OF OLD ZOO KEEPERS

Janine di Giovanni talks to the

custodians of a great British institution which is set for extinction

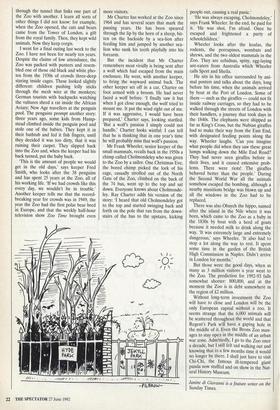

MR RAY CHARTER, keeper of the 13 big cats at the London Zoo, stared forlorn- ly at an Indian lion sprawled inside his leafy enclosure. He shook his head. 'When I think that by next Christmas this place will be empty, nothing here, just an empty space to be vandalised, I can't believe it,' he says miserably. 'The Zoo simply will not exist.' Mr Charter has spent most of his life working at the 166-year-old London Zoo; and although the Emir of Kuwait's dona- tion of £1 million has been a welcome fillip it may not be enough to save the Zoo — it is in dire need of more long-term investment.

Like most of the keepers, Mr Charter feels a profound attachment to the animals and their domain inside the gates of Regent's Park. 'This is not the sort of place that is easy to shake,' he says simply, and points me in the direction of the elephants. He tells me about the most famous London Zoo elephant, the massive one responsible for putting the word 'jumbo' in the dictio- nary.

Another keeper tells me how the ele- phants got testy when the first jet liners started. 'When the first Comet flew in 1957, the elephants got incredibly upset, started trying to run home,' he says. At the sound of the propellers, they ran charging

through the tunnel that links one part of the Zoo with another. I learn all sorts of other things I did not know: for example, when the Zoo opened, the cats and bears came from the Tower of London, a gift from the royal family. Then, they kept wild animals. Now they keep corgis.

I went for a final outing last week to the Zoo. I have not been for nearly ten years. Despite the claims of low attendance, the Zoo was packed with punters and resem- bled one of those old black and white pho- tos from the 1930s of crowds three-deep staring inside cages. These looked slightly different: children pushing lolly sticks through the mesh wire at the monkeys; German tourists with backpacks watching the vultures shred a rat inside the African Aviary; New Age travellers at the penguin pool. The penguins prompt another story: three years ago, some kids from Hamp- stead climbed inside the penguin pool and stole one of the babies. They kept it in their bathtub and fed it fish fingers, until they decided it was too dirty, that it was ruining their carpet. They slipped back into the Zoo and, when the keeper had his back turned, put the baby back.

`This is the amount of people we would get in the old days,' says keeper Fred Smith, who looks after the 38 penguins and has spent 25 years at the Zoo, all of his working life. 'If we had crowds like this every day, we wouldn't be in trouble.' Another keeper tells me that the record- breaking year for crowds was in 1949, the year the Zoo had the first polar bear bred in Europe, and that the weekly half-hour television show Zoo Time brought even

more visitors.

Mr Charter has worked at the Zoo since 1964 and has several scars that mark the passing years. He has been speared through the lip by the horn of a sheep, bit- ten on the backside by a sea-lion after feeding him and jumped by another sea- lion who sunk his teeth playfully into his forearm.

But the incident that Mr Charter remembers most vividly is being sent after a wolf which had escaped from the main enclosure. He went, with another keeper, to bring the wayward animal back. The other keeper set off in a car, Charter on foot armed with a broom. He had never faced a wolf before. 'I finally saw it but when I got close enough, the wolf tried to mount me. It put the wind right out of me. If it was aggressive, I would have been prepared,' Charter says, looking startled. `But a wolf's passion I simply could not handle.' Charter looks wistful: I can tell that he is thinking that in one year's time he will probably miss that wolf's passion.

Mr Frank Wheeler, senior keeper of the small mammals, recalls back in the 1950s a chimp called Cholmondeley who was given to the Zoo by a sailor. One Christmas Eve, the bored chimp picked the lock of his cage, casually strolled out of the North Gate of the Zoo, climbed on the back of the 74 bus, went up to the top and sat down. Everyone knows about Cholmonde- ley. Ray Charter adds his version of the story: 'I heard that old Cholmondeley got to the top and started swinging back and forth on the pole that ran from the down- stairs of the bus to the upstairs, kicking people out, causing a real panic.'

`He was always escaping, Cholmondeley,' says Frank Wheeler. In the end, he paid for it. 'He was shot, I'm afraid. Once he escaped and frightened a party of schoolchildren.'

Wheeler looks after the koalas, the rodents, the porcupines, wombats and shrews, and the two oldest mammals in the Zoo. They are echidnas, spiny, egg-laying ant-eaters from Australia which Wheeler calls Sport and Sheila.

He sits in his office surrounded by ani- mal posters and talks about the days, long before his time, when the animals arrived by boat at the Port of London. Some of them — such as the giraffes — could not fit inside railway carriages, so they had to be walked through the streets of London with their handlers, a journey that took days in the 1840s. The elephants were shipped as far as King's Cross, but the Nubian giraffes had to make their way from the East End, with designated feeding points along the way. Wheeler laughs. 'Can you imagine what people did when they saw these great lumps walking down the Mile End Road?

They had never seen giraffes before in their lives, and it caused extensive prob- lems. There were riots! The giraffes behaved better than the people.' During the Second World War all the animals somehow escaped the bombing, although a nearby munitions bridge was blown up and all the windows in the Zoo had to be replaced.

There was also Obaych the hippo, named after the island in the Nile where it was born, which came to the Zoo as a baby in the 1830s by boat with a herd of goats because it needed milk to drink along the way. 'It was extremely large and extremely dangerous,' says Wheeler. 'It also had to stop a lot along the way to rest. It spent some time in the garden of the British High Commission in Naples. Didn't arrive in London for months.'

But those were the good days, when as many as 3 million visitors a year went to the Zoo. The prediction for 1992-93 falls somewhat shorter: 800,000, and at the moment the Zoo is in debt somewhere in the region of £2 million.

Without long-term investment the Zoo will have to close and London will be the only European capital without a zoo. It seems strange that the 6,000 animals will be scattered throughout the world and that Regent's Park will have a gaping hole in the middle of it. Even the Bronx Zoo man- ages to stay open in the middle of an urban war zone. Admittedly, I go to the Zoo once a decade, but I still felt sad walking out and knowing that in a few months time it would no longer be there. I shall just have to visit Chi-Chi, the famous ill-tempered giant panda now stuffed and on show in the Nat- ural History Museum.

Janine di Giovanni is a feature writer on the Sunday Times.

Previous page

Previous page