RIGHT-WING CONSPIRACY

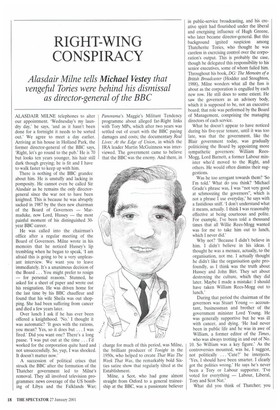

Alasdair Milne tells Michael Vestey that

vengeful Tories were behind his dismissal

as director-general of the BBC ALASDAIR MILNE telephones to alter our appointment. 'Wednesday's my laun dry day,' he says, 'and as it hasn't been done for a fortnight it needs to be sorted out.' We agree to meet a day earlier.

Arriving at his house in Holland Park, the former director-general of the BBC says, 'Right, let's go round to the pub.' He is 70 but looks ten years younger, his hair still dark though greying; he is fit and I have to walk faster to keep up with him.

There is nothing of the BBC grandee about him. He is unstuffy and lacking in pomposity. He cannot even be called Sir Alasdair as he remains the only directorgeneral since the war not to have been knighted. This is because he was abruptly sacked in 1987 by the then new chairman of the Board of Governors — Marmaduke, now Lord, Hussey — the most painful moment of his distinguished 30year BBC career.

He was called into the chairman's office after a regular meeting of the Board of Governors. Milne wrote in his memoirs that he noticed Hussey's lip trembling when he began to speak, 'I am afraid this is going to be a very unpleasant interview. We want you to leave immediately. It's a unanimous decision of the Board . . . You might prefer to resign — for personal reasons.' Stunned, he asked for a sheet of paper and wrote out his resignation. He was driven home for the last time by his BBC chauffeur and found that his wife Sheila was out shopping. She had been suffering from cancer and died a few years later.

Over lunch I ask if he has ever been offered a knighthood. 'No.' I thought it was automatic? 'It goes with the rations, you mean? Yes, so it does but . . . I was fired.' Did you want one? There's a long pause. 'I was put out at the time . . . I'd worked for the corporation quite hard and not unsuccessfully. So, yup, I was shocked. It doesn't matter now.'

A succession of political crises that struck the BBC after the formation of the Thatcher government led to Mibe's removal. They all involved television programmes: news coverage of the US bombing of Libya and the Falklands War; Panorama's Maggie's Militant Tendency programme about alleged far-Right links with Tory MPs, which after two years was settled out of court with the BBC paying damages and costs; the documentary Real Lives: At the Edge of Union, in which the IRA leader Martin McGuinness was interviewed. The government came to believe that the BBC was the enemy. And there, in charge for much of this period, was Milne, the brilliant producer of Tonight in the 1950s, who helped to create That Was The Week That Was, the remarkably bold Sixties satire show that regularly tilted at the Establishment.

Milne, a Scot, who had gone almost straight from Oxford to a general traineeship at the BBC, was a passionate believer in public-service broadcasting, and his creative spirit had flourished under the liberal and energising influence of Hugh Greene, who later became director-general. But this background ignited suspicion among Thatcherite Tories, who thought he was careless in exercising control over the corporation's output. This is probably the case, though he delegated this responsibility to his senior executives, some of whom failed him. Throughout his book, DG: The Memoirs of a British Broadcaster (Hodder and Stoughton, 1988), Milne wonders what all the fuss is about as the corporation is engulfed by each new row. He still does to some extent. He saw the governors as an advisory body, which it is supposed to be, not an executive board; that role was performed by the Board of Management, comprising the managing directors of each service.

What he doesn't appear to have noticed during his five-year tenure, until it was too late, was that the government, like the Blair government today, was gradually politicising the Board by appointing more sympathetic governors: William ReesMogg, Lord Barnett, a former Labour min ister who'd moved to the Right, and others. He would often dismiss their sug gestions.

Was he too arrogant towards them? `So I'm told.' What do you think? 'Michael Grade's phrase was, I was "not very good at schmoozing the governors", which is not a phrase I use everyday,' he says with a fastidious sniff. 'I don't understand what it means, actually. I think I was reasonably effective at being courteous and polite. For example, I've been told a thousand times that all Willie Rees-Mogg wanted was for me to take him out to lunch, which I never did.'

Why not? 'Because I didn't believe in him. I didn't believe in his ideas. I thought he was a menace, actually, to the organisation, not me. I actually thought he didn't like the organisation quite profoundly, as I think was the truth about Hussey and John Birt. They set about destroying the culture, which they did later. Maybe I made a mistake: I should have taken William Rees-Mogg out to lunch.'

During that period the chairman of the governors was Stuart Young — accoun tant, businessman and brother of the government minister Lord Young. He was generally supportive but he was ill with cancer, and dying. 'He had never been in public life and he was in awe of William, a former editor of the Times, who was always trotting in and out of No. 10. So William was a key figure.' As the controversies mounted, was he, I suggest, not politically . . . 'Cute?' he interjects. 'Yes, I should have been smarter. I clearly got the politics wrong.' He says he's never been a Tory or Labour supporter. 'I've voted for everything — Labour, Liberal, Tory and Scot Nat.'

What did you think of Thatcher; you obviously disliked her? 'No, not at all. The first time I met her was when she asked me down for a drink when I became DG and she was extremely pleasant and we argued about the licence fee.' So when did you come to dislike her? 'Never. I spoke to Bernard Ingham quite a lot and at one time [nine months before he was sacked] I said I want the prime minister to come to lunch and he said, not a chance. So I knew I was a marked man.' Do you really think that Thatcher put Hussey in there to get rid of you? 'Yes, I think so . . . she had decided.' His appointment took everyone by surprise. He had been chief executive and managing director of Times Newspapers before Rupert Murdoch bought it and a director afterwards, and his wife was a lady-in-waiting to the Queen.

'I couldn't understand why he'd been appointed. When he arrived, he was cheerful, jolly, and we would have a table at Claridge's every day for lunch.' In no time at all Milne sensed trouble. After he'd been forced to abandon the Maggie's Militant Tendency libel action, 'things became dicky. I mean, they were dicky from 18 months back from the Real Lives row, which really caused my downfall. The row over Real Lives was bitter and sharp. Some of the tensions with the government were terrible.

'Actually, I've made my peace with Hussey,' he says casually. 'He invited me to lunch last year. I told him that my sacking had been brutal and barbarous. "Yes, it was," he replied, which completely disarmed me. I said, "You didn't like the BBC and wanted to destroy it." He said, "No, I don't agree with that." The main purpose, after 13 years, was to clear the air about how they dealt with me, as I regard myself as the last true director-general of the BBC. After all, I was a producer. Nobody else had been. And afterwards we had Michael Checkland, an accountant, and then we had the commercial television people [John Birt and Greg Dyke] and they don't understand the BBC.'

He believes that John (now Lord) Birt was a disaster. He had applied to the BBC for a job during Milne's time. 'Of course, I turned him down — flat! David Frost kept saying to me, "There's this wonderful man at London Weekend Television." I wouldn't have him near me. I said, "No, he's a systems man, an engineer. I'm not having him around here. Be done with it! We've got lots of engineers far better than he." '

He pauses and looks sad for a moment. 'But the funny thing is, the call was made and Birt was, for the best part of ten years, running the place and destroying the culture. The BBC is a great institution of state and is the benchmark, or was, for quality-programme production, as all the commercial television people will tell you. One of the great ironies of life is that Birt and Christopher Bland [the present chairman] both come from a fairly small weekend commercial company, which we derided. And they're running the BBC. They hated the BBC. That is terrible, actually. You know, we spent all of our lives building it up' — his voice has begun to quaver and he looks sombre — 'and to have it ground down by people from commercial television is hard to take, really.'

Perhaps he has a point. Can anyone honestly say that BBC television programmes are better than they were 13 years ago? But, I tell him, your BBC wasn't absolutely perfect, as I know from my own time there, Was it not overmanned? 'I'm told constantly that I ran an organisation that was bloated and bureaucratic. I'm told that it now takes nine months to get a programme decision. In my time, John O'Sullivan who wrote Only Fools and Horses — he was a scene shifter — sent to the head of comedy a thing called Citizen Smith, and eight weeks later it was on the air.

'Cedric Messina, who was in charge of Play of the Month, came to me when I was managing director of television and said to me, "Let's put on all the plays of Shakespeare." I thought, Good God Almighty, I never thought of that. I said okay, and 24 hours later I'd sorted out the budget and we did all the plays of Shakespeare in six years. We weren't bureaucratic, we were quite swift, actually. BBC television hasn't made a Shakespeare play for nearly 20 years and its programmes now are substandard.'

Apart from a spell chairing a government taskforce on the future of Gaelic broadcasting in Scotland — he speaks it fluently — Milne spends his summers fishing and his winters shooting. So is he the forgotten man of broadcasting? He looks agitated for the first time. 'Is that what you're going to say about me?' I don't know, I answer truthfully.

It had crossed my mind but now I'm not so sure. His era was, after all, the last to produce consistently high-quality and innovative BBC television. 'As I said, I see myself as the last true director-general of the BBC.'

Previous page

Previous page