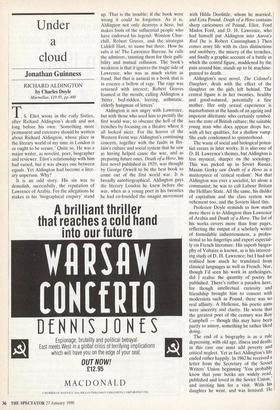

Under a cloud

Jonathan Guinness

RICHARD ALDINGTON by Charles Doyle

Macmillan, £19.95, pp.400

T. S. Eliot wrote in the early Sixties, after Richard Aldington's death and not long before his own: 'Something more permanent and extensive should be written about Richard Aldington, whose place in the literary world of my time in London is or ought to be secure.' Quite so. He was a major writer, as novelist, poet, biographer and reviewer. Eliot's relationship with him had varied, but it was always one between equals, Yet Aldington had become a liter- ary unperson. Why?

It is an odd story. His sin was to demolish, successfully, the reputation of Lawrence of Arabia. For the allegations he makes in his 'biographical enquiry' stand up. That is the trouble; if the book were wrong it could be forgotten. As it is, Aldington not only destroys a hero, but makes fools of the influential people who have endorsed his legend: Winston Chur- chill, Robert Graves, and the strategist Liddell Hart, to name but three. How he rubs it in! The Lawrence Bureau, he calls the admirers, taunting them for their gulli- bility and mutual collusion. The book's weakness is that it ignores the tragic side of Lawrence, who was as much victim as fraud. But that is natural in a book that is in essence a bellow of rage. The rage was returned with interest; Robert Graves foamed at the mouth, calling Aldington a `bitter, bed-ridden, leering, asthmatic, elderly hangman of letters'.

Aldington is not angry with Lawrence, but with those who used him to prettify the first world war, to obscure the hell of the trenches by focusing on a theatre where it all looked nicer. For the horror of the Western Front was Aldington's continuing concern, together with the faults in Bri- tain's culture and social system that he saw as having helped cause the war, and as preparing future ones. Death of a Hero, his first novel published in 1929, was thought by George Orwell to be the best book to come out of the first world war. It is broadly autobiographical. Aldington guys the literary London he knew before the war, when as a young poet in his twenties he had co-founded the imagist movement

with Hilda Doolittle, whom he married, and Ezra Pound. Death of a Hero contains sharp caricatures of Pound, Eliot, Ford Madox Ford, and D. H. Lawrence, who had himself put Aldington into Aaron's Rod (he is Robert Cunningham.) Then comes army life with its class distinctions and snobbery, the misery of the trenches, and finally a graphic account of a battle in which the central figure, maddened by the pain around him, stands up to be machine- gunned to death, Aldington's next novel, The Colonel's Daughter, deals with the effect of the slaughter on the girls left behind, The central figure is in her twenties, healthy and good-natured, potentially a fine mother. Her only sexual experience is masturbation at the hands of an ageing and impotent dilettante who certainly symbol- ises the state of British culture; the suitable young man who does appear drops her, with all her qualities, for a shallow vamp. She ends condemned to spinsterhood.

The waste of social and biological poten- tial recurs in later works. It is also one of D. H. Lawrence's themes, but Aldington is less mystical, sharper on the sociology. This was picked up in Soviet Russia; Maxim Gorky saw Death of a Hero as a masterpiece of 'critical realism'. Not that Aldington was ever a socialist, let alone a communist; he was to call Labour Britain the Hellfare State. All the same, his dislike of capitalism and the class system was vehement too, and the Soviets liked this.

Professor Doyle reminds us how much more there is to Aldington than Lawrence of Arabia and Death of a Hero. The list of his works covers more than four pages, reflecting the output of a scholarly writer of formidable industriousness, a profes- sional to his fingertips and expert especial- ly on French literature. His superb biogra- phy of Voltaire is known, as is his interest- ing study of D. H. Lawrence; but I had not realised how much he translated from classical languages as well as French. Nor, though I'd seen his work in anthologies, did I realise the quantity of poetry he published. There's rather a paradox here, for though intellectual curiosity and friendship brought him to consort with modernists such as Pound, there was no real affinity. A Hellenist, his poetic aims were sincerity and clarity. He wrote that the greatest poet of the century was Roy Campbell — though this may have been partly to annoy, something he rather liked doing. The end of a biography is as a rule depressing, with old age, illness and death; in this case one must add poverty and critical neglect. Yet in fact Aldington's life ended rather happily. In 1962 he received a letter from the Secretary of the Soviet Writers' Union beginning 'You probably know that your books are widely read, published and loved in the Soviet Union,' and inviting him for a visit. With his daughter he went, and was lionised. He

refused to sign an anti-American docu- ment; nobody minded. He went to Tol- stoy's house at Yasnaya Polyana, he saw the sights of Moscow and (as he called it) St Petersburg. Soon afterwards he died.

Professor Doyle has given us, more than 25 years late, the study Eliot asked for. The essentials are there. I shall not find fault with it, because as an admirer of Aldington I am so grateful that it has appeared at last.

Previous page

Previous page