SLAYING THE MAGIC DRAGON

The American authorities have declared that this is at best a phony war

Washington WHO said: 'Drugs threaten our stability. Drugs threaten our safety and drugs threaten the soul of our city'? Here's a hint: it's the same man whose rap routine to primary school pupils goes like this: My mind is a pearl;

I can do anything in the whole world. If it's to be, It's up to me - Keep myself drug-free!

Keep myself drug-free!

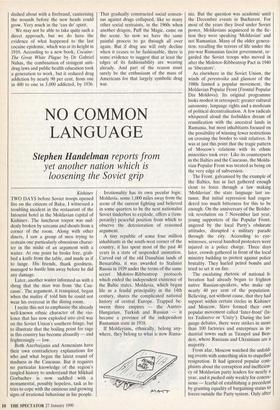

There are no prizes for guessing that the answer is the Honourable Marion Barry, Jnr, Mayor of Washington, who last week showed that at least he was sincere in his belief in the first two lines of that song. With a characteristic disregard for the many perils involved, Barry had gone to visit an old amie, a stunning black model called Rasheeda Moore, at her hotel room in central Washington. There he was intro- duced to another woman who turned out to be an undercover FBI agent. From this second woman, it is alleged, he bought some crack cocaine, which he then pro- ceeded to smoke. The whole episode was recorded by a hidden video camera. As Barry got up to leave, police and FBI agents who had been camped in the two adjoining rooms burst in and arrested him.

It now seems that Barry was luckier on earlier occasions when, in the midst of a number of other outrages to middle-class white proprieties, it was rumoured that he had used drugs. But the whole pattern of his behaviour suggests that he owes his swagger less to the clinical condition known as the addict's 'denial' than to a very uncertain grasp of reality in general. Last year, when there were 438 people murdered in Washington, he was quoted as saying that 'outside of the killings, we have one of the lowest crime rates in the country'. And earlier on the day he was arrested, a day on which the city recorded its 28th murder in 17 days, the mayor had given a news conference during which he had claimed that `the war on crime and violence is succeeding'.

We're winning, too, quite frankly. . . . Win- ning is more than just homicides. Winning is the whole city getting involved, When I say `winning', you've got to define it by neigh- bourhoods. . . . There's more to city govern- ment than these murders, A mayor has a responsibility for all the services of govern- ment, not just homicides. And we're going to do that well.

The amazing thing is that it still may be that he is doing well. At the weekend there were not yet many observers of his political career who were in a hurry to write him off. Barry is a past master of the politics of symbolism, learned in his early years in the

civil rights movement, and black politics is so much about symbolism that, like the mayor of Newark a few years ago who was re-elected while in jail, he retains a con- siderable core of support in the 'neighbour- hoods' even now. 'The mayor did so much for us poor people. I would never go against him,' said one of his supporters. `He's just another victim,' said another. These are spokesmen for the psychology of the ghetto, which is actually better served by a symbol of that victimisation in which it so devoutly believes than by a mere admin- istrator.

Recent and unprecedented successes of such mainstream black politicians as Doug- las Wilder in Virginia and David Dinkins in New York suggest that the neighbour- hoods might now decide that they don't want to be ghettos any more, that they prefer efficiency and probity to symbolism. But if they do there will always be a place for Barry, the originator of the oxymoronic `war on violence', in that other symbolic war — which some would say is moronic tout court — the 'war on drugs'. Mr William Bennett, its field marshal, must have some use for a man with plenty of experience and a ready-made rap routine as a witness against drugs — especially if he has lately reformed.

The 'war' metaphor, which is a legacy from Lyndon Johnson's 'war on poverty', has never been very satisfactory. In none of these 'wars' is anything that could be called a final victory even imaginable: there will always be poor people; there will always be drugs and drug-users; there will always be civil violence. The 'war', there- fore, consists of a series of gestures — a drug bust, the capture of a cocaine ship- ment, an invasion of Panama — all highly publicised, all with clear-cut good and bad guys, and all triumphs for the good. These are just like the wars in Nineteen Eighty- Four, only adapted to democratic condi- tions.

The war on drugs, especially, has always got to be a phony war, a hypocritical war, to the extent that it is a war against ourselves and those of our appetites whose satisfaction it is that enriches the drug- dealers. This is less obvious in Washington than it is in Latin America, where they are used to receiving moral lectures from the colossus of the North. There the war is more like a real war, and even America's allies routinely notice her schizophrenia, if not hypocrisy, with a mixture of ruefulness and disgust. That decorated veteran of the drug wars, El Espectador of Bogota under- scored the same point when it ran a photo of Barry, whom it referred to as Alcalde drogadicto (drug addict mayor), with the mayors of New York and Bogota at an anti-drug mayors' meeting.

Back in the States, many of those who see this contradiction most clearly, includ- ing such luminaries of the Right as Milton Friedman, William Buckley and the former Secretary of State, George Schultz, argue for legalisation, or at least decriminalisa- tion, of drugs. They point not only to the stupidity of inveighing against our victual- ler for filling our grocery order exactly as we made it out, and to the more obvious costs of giving him the occasional bashing into the bargain, but also to the damage we do to our relations with other countries by giving what seems a merely symbolic strug- gle such a high priority.

At the moment, in addition to her problems with virtually the whole of Latin America on account of the Panama inva- sion, the United States has strained rela- tions with three countries in particular because of the drug war. Mexico is cross because of an NBC television 'docudrama' about the killing of an American narcotics agent which depicts the Mexican anti-drug effort, if not the whole Mexican govern- ment, as badly managed and corrupt. Peru is cross because 'our boys' in Panama have been rude to her diplomats there, who have given shelter to some of Noriega's men. Colombia is cross because, in Presi- dent Bush's post-Panama enthusiasm, he dispatched an aircraft carrier to linterdice supplies of drugs as they left her shores.

Such half-comic episodes are reminis- cent of the President's declaration of the war' last September. Symbolism suggested that he surprise and shock his national television audience by holding up a bag of crack cocaine that had been bought 'across the street' from the White House. In the end, this is what he did, but it was not done without mishap. The agent whose job it was to record the purchase of three ounces of crack in Lafayette Square on videotape was assaulted by a homeless person and missed it, while the agent who made the Purchase failed to record his conversation with his dealer because of a faulty mic- rophone. That dealer, an 18-year-old Washington schoolboy, almost missed the appointment because he didn't know where the White House was. 'Oh, you mean where Reagan lives!' he finally said.

Yet there is another American tradition besides that of sanctimoniousness and hYPocrisy and that is the tradition of 'Can do!' It is not in the American character simply to give a weary shrug of the shoulders and say, 'I can do no more.' The politicians understand this better than the libertarian philosophers, and they do mean to accomplish something. The drug war, therefore, always teeters between the merely symbolic and the marginally effec- tual and cannot be dismissed as mere Public relations.

The drug barons of Medellin are similar- ly confused, and confusing, when it comes to distinguishing between the symbolic and the practical: their highly publicised 'sur- render' last week in exchange for an amnesty and a guarantee that they would not be extradited to the United States was the second such gesture they have made in a month. It was greeted with considerable scepticism both in Washington and in Bogota, yet it probably indicates some genuine wilting in the face of government determination to resist.

There are some other indications of success at the margin. In the late 1980s, as crack use doubled, other drug use has declined by 37 per cent. There is much better international co-operation in the detection and prevention both of drug smuggling and of money laundering now that drugs are beginning to be seen as a worldwide problem and not just an Amer- ican one. There has also been progress in cutting off the supply of 'chemical precur- sors', used in the processing of drugs, 70 per cent of which are supplied by the United States (new laws require that the manufacturers identify the end users); in moving interception efforts closer to the point of supply, where they are more effective; in economic assistance to pro- ducer countries in order to limit depend- ence on the coca crop; and in military assistance, especially to Peru, where pro- ducers are allied to guerrilla insurgencies.

This week, ( President Bush is to announce his spring offensive. In addition to (a little) more money for (a few) `high-intensity drug trafficking areas' such as New York and Miami, this is likely to include the death penalty for 'major drug kingpins' — even when they are not otherwise guilty of any capital crime. The former dictator of Panama, by the way, has had to be designated as an inferior sort of trafficker, a minor, back-row pin, because Bush is supposed to have promised the Vatican not to fry him in 'Old Sparky', Florida's electric chair.

Such softness is not for the likes of Senator Gramm of Texas and Representa- tive Gingrich (also known as Newt) of Georgia. These warlike lawmakers have anticipated the President by putting for- ward a plan for a five-year national drug emergency. This would provide, among other things, for mandatory sentences and no parole for drug felons, more, prisons and, in the meantime, tents on military bases to house additional criminals, man- datory drug testing of all those arrested or convicted of any crime, and random drug testing of parolees, high school pupils, government employees, private em- ployees, drivers and pretty well anybody else who looks as if he (or, indeed, she) needs it.

Bush may not buy all this, but the half-worrying and half-encouraging thing is that a lot of Americans might. The spirit of `can do' requires a lot of determination. A recent poll showed that 52 per cent of Americans were willing to have their homes and 67 per cent their cars searched without a warrant. More than half favoured mandatory drug testing for every- one and fully two-thirds for all high school students. This may be the first flush of bellicose enthusiasm, but Messrs Gramm and Gingrich, both of whom are supposed to aspire to higher things, appear to be on to a political winner here. Senator Gramm's diagnosis of the situation here follows. The drug problem is a dragon that can't be killed with one bullet. We've got to put a bullet in each of the dragon's heads.'

American politicians are not always punctilious about their metaphors. Senator Sasser of Tennessee said of a tax proposal last week that 'this thing could sprout wings and become an irresistible political juggernaut that will thunder through the halls of Congress like a rolling locomotive'. I wonder if his colleague, Senator Gramm, might not have been groping towards another sort of worm than a dragon, which, so far as I am aware, is not normally represented as having more than the com- mon number of heads. The equally legen- dary hydra of the Lernaean marshes, however, was supposed to have a hundred. Its response to bullets in them is not recorded, but when.each was chopped off two more were said to have grown in its place. That might have been a more appropri- ate comparison, given the seeming impos- sibility of stopping even drug-users with as much to lose as Mayor Barry from obtain- ing the thrill that they are after. As drug seizures have increased by 50 per cent drug supplies and prices seem not to have been affected in the least. The laws of supply and demand, which are what made Amer- ica great, would seem ever to be extruding one of the replacement heads even as the compulsive nature of the demand pops out

the other. Yet the hydra was killed in the end. I believe that Hercules's charioteer

dashed about with a firebrand, cauterising the wounds before the new heads could grow. Very much in the 'can do' spirit.

We may not be able to take quite such a direct approach, but we do have the evidence of what happened to the last cocaine epidemic, which was at its height in 1910. According to a new book, Cocaine: The Great White Plague by Dr Gabriel Nahas, the combination of stringent anti- drug laws and public health education took a generation to work, but it reduced drug addiction by nearly 90 per cent, from one in 400 to one in 3,000 addicted, by 1936.

That gradually constructed social consen- sus against drugs collapsed, like so many other social restraints, in the 1960s when another dragon, Puff the Magic, came on the scene. So now we have the same painful process to go through all over again. But if drug use will only decline when it ceases to be fashionable, there is some evidence to suggest that at least the edges of its fashionability are wearing already. And part of the reason must surely be the enthusiasm of the mass of Americans for that largely symbolic drug war.

Previous page

Previous page