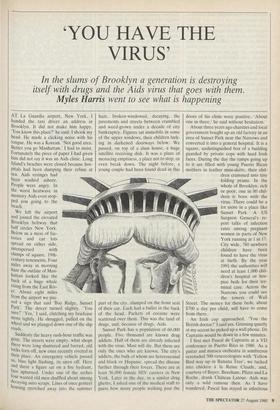

'YOU HAVE THE VIRUS'

In the slums of Brooklyn a generation is destroying itself with drugs and the Aids virus that goes with them.

Myles Harris went to see what is happening

AT La Guardia airport, New York, I handed the taxi driver an address in Brooklyn. It did not make him happy. 'You know this place?' he said. I shook my head. He made a clicking noise with his tongue. He was a Korean. 'Not good area. Better you go Manhattan.' I had to insist. Fortunately the piece of paper I had given him did not say it was an Aids clinic. Long Island's beaches were closed because hos- pitals had been dumping their refuse at sea. Aids syringes had been washed ashore. People were angry. In the worst heatwave in memory Aids even stop- ped you going to the beach.

We left the airport and joined the elevated Brooklyn beltway that half circles New York. Below us a mess of fac- tories and car - lots Spread on either side, Suddenly the heavy rush-hour traffic was gone. The streets were empty, what shops there were long shuttered and barred, old locks torn off, new ones recently riveted in their place. An emergency vehicle passed us, blue light flashing, its siren off. Here and there a figure sat on a fire hydrant, face upturned. Under one of the arches four wasted old men shuffled about among decaying auto scraps. Lines of once genteel housing stretched away into the summer haze, broken-windowed, decaying, the pavements and streets between crumbled and weed-grown under a decade of city bankruptcy. Figures sat immobile in some of the upper windows, their children lurk- ing in darkened doorways below. We passed, on top of a slum house, a huge satellite receiving dish. It was a place of menacing emptiness, a place not to stop, or even break down. The night before, a young couple had been found dead in this part of the city, slumped on the front seat of their car. Each had a bullet in the back of the head. Packets of cocaine were scattered over them. This was the land of drugs, and, because of drugs, Aids.

Sunset Park has a population of 60,000 people. Five thousand are known drug addicts. Half of them are already infected with the virus. Most will die. But these are only the ones who are known. The city's addicts, the bulk of whom are heterosexual and black or Hispanic, spread the disease further through their lovers. There are at least 56,000 female HIV carriers in New York. Later in the day, in a similar drug ghetto, I asked one of the medical staff to guess how many people walking past the doors of his clinic were positive. 'About one in three,' he said without hesitation.

An Irish cop approached. 'You the British doctor?' I said yes. Grinning quietly at my accent he picked up a wall phone. Dr Caprariis would be down in a few minutes.

I first met Pascal de Caprariis at a VD conference in Puerto Rico in 1980. As a guitar and maraca orchestra in sombreros serenaded 500 venereologists with 'Yellow Bird way up in Banana Tree', we tucked into chicken a la Reine Claude, and, courtesy of Bayer, Beecham, Pfizer and La Roche, drank Château Latour. Aids was only a wild rumour then. As I have wandered. Pascal has stayed in infectious

diseases. It is a difficult and sometimes risky business.

As we shook hands I asked him if he was, not worried by the obviously vicious neigh- bourhood — he is a very thin man in a world of violence where the fist must count. He grinned at me over a pair of mild horn-rims. 'It was far worse three years ago,' he said. Then they had four street gangs fighting for territory in the area. There had been knife and gun fights around the hospital. One morning he came into casualty just as a man fell out of a clinic door in front of him with blood pumping from a hole in his neck. There had been a street accident and a gang had chased the driver into casualty and shot him. But the gangs were all dead now. I asked if they had killed each other. He smiled apologetically and shook his head. 'No, just drugs and overdoses. And,' he added, 'they have left behind an Aids explosion.'

The Aids clinic was upstairs. He begged me not to call it that. 'Nowadays,' he said, 'they are called Family Health Centres.' It was like any other outpatients I have seen, if a bit dustier. Nearly all the patients were Puerto Rican. The staff were all young and quiet. Most could speak Spanish. I was introduced to a social worker, a small and very pretty Puerto Rican girl, and to a Californian nutritionist who had learnt the fluent Spanish necessary to work here while on an aid project in Nicaragua. In a side office a very tired looking young man introduced himself as the psychologist. Somebody gave me a Dr Gillespie coat.

Many people refuse to believe that Aids can be spread only by sex, blood or needles. Accordingly its victims are shun- ned. Many die alone and ashamed. Pascal told me he had had a call from one doctor begging him not to refer any more cases. The doctor felt obliged to burn his clothes after each case and complained that he was running out of old suits. The purpose of the clinic was to break the isolation such attitudes bring. It provided patients with basic medical care, gave them advice about food, housing, social security and health, and, by introducing them to other patients with the disease, made them feel they were not alone in the world. It was practising the oldest adage in medicine, To cure seldom, to comfort always'. It seemed to work.

New patients were seen by a social worker. This morning she talked to a young man who had just discovered his lover had Aids. He would know the result of his own test in two weeks. She referred to it as 'knowing if you had the virus'. The young man was hysterical with fear. He said. 'After I take food for my lover to the hospital I go home, I am alone. I go crazy. I can't concentrate. I don't remember my own name, I have nobody, I am an outcast. The world is so mean and rough. Even my mother has turned on me. When I go to her it is no longer, come to me, my baby — oh no! It is now a very different thing!'

Another patient with the disease was brought in to calm him. If anything his situation was worse. His lover was in prison. They would probably never meet alone again before death. He talked quiet- ly about practical everyday things with the boy. It had a slight effect. It would take time, the social worker said.

In group therapy a man talked about his street life. 'I began to shoot coke. I said to myself, "I am cool now." Cool nothing! I needed many more bags. Now my life is in Jesus's hands. Jesus has another world for us.' He had been in prison. Prisoners slept 30 to a dormitory and he had had terrible diarrhoea. He spoke with bitter precision of the number of stools he passed — 15 during the day and 11 at night. At night he had to beg the guards to let him out to the toilet. Many of the other prisoners had Aids but were frightened to admit it. You could be killed for having Aids. Many of them had TB or other complications of the illness. In the morning the washbasin in the cell was filled with blood and sputum. He described how the guards would manacle him hand and foot before taking him to the local hospital.

Aman opposite him said how in some hospitals they put a big yellow card at the end of the bed to show you were infectious. Then the cleaners and the orderlies would not come near you. Even some of the nurses were frightened. 'One put on a mask and gloves to put a thermometer under my arm.' He shrugged and said, 'But I am not frightened. Only God can take my life.'

The prayers for reprieve from apparent- ly healthy young men in the prime of life struck a dreadful note in the blank, neon- lit offices with their official steel cup- boards. It was like death row without the guards.

Afterwards I asked the young psycholog- ist how he stood it. Sometimes, he said, the meetings were terrible. He had had women who publicly forgave their lovers for giving them and their children Aids. You could keep calm at the time but at night, going home on the subway, he would find himself weeping over some gushy sentimental story in a newspaper. I said to him that the prayers did not sound so convincing. It was a Spanish thing, he said, a ritual in the face of death. None of these people had been saints.

In the afternoon I went to talk to some black doctors and nurses in Broadway, four miles into a slum across the East River from Manhattan, that the theatre critics will never see. There, amid a litter of auto hulks and broken houses, the city has built a health clinic. It is really an Aids clinic, since half the patients in the district have the disease but, like Pascal's unit, calling it a Family Health Centre takes away some of the stigma. A black woman doctor runs it. She was fat and matronly and wore the scarf of the Black Muslim movement around her head. (The Muslims are an Islamic radical black self-help group which rejects white assistance. They follow the traditional Islamic proscription of all drugs.) I asked her, 'If you gave a black youth $200 and told him to start walking out of all this before he got Aids, where could he go?' She was decent and tough- minded. Money, she said, was not the answer. There were only three ways out. The army, education or the Black Mus- lims. If the Black Muslims reached you in prison they could turn you round, get you off drugs and give you a purpose. The army would take you if you were HIV negative, and if you wanted education you had to stay the hell out of the public school system. She spent all her salary on educat- ing her children in private schools. A black nurse nodded her head in agreement. The public school system was a mess. It was violent, nothing was taught and most kids left it completely illiterate. To send your child there was to send him directly into the arms of the drug dealer. In the waiting room Afro-Caribbeans lolled on plastic chairs.

Outside, the six armed security men who would be there all night were already starting to activate the alarms. I looked at the torch-proof metal grilles on the win- dows and asked about getting back. One of the medical staff offered to drive me to a white area of Brooklyn. It took about ten minutes. Somewhere about a mile from the Brooklyn Bridge we crossed an invisible line. The crumbling houses and sleaze gave way to ugly apartments with janitors and plate-glass doors. Rows of open shops appeared and the streets became wider. This was the American version of Johan- nesburg, ade facto apartheid.

The Centre for Disease Control in Atlanta estimates that by 1991 12.5 million Americans will have the virus and 250,000 will be dying from it. All those who have the virus are expected to succumb even- tually. Most cases will come from the cities. New cases in New York are now running at 341 per month and rising. With drug addiction replacing homosexuality as the commonest method of transmission it Is a disease which is going to hit blacks and Hispanics hardest.

In some parts of the Bronx three out of four of the population are already infected, in Brooklyn one in three. Whole communi- ties are going to die. Already there are hints of it. The rotting tenements are slowly emptying. Yuppies are creeping, decorating brushes in hand, into what were once the barracks of drug dealers, pimps, prostitutes and their victims. Traffic will still roar up and down the elevated belt- ways into Manhattan. But below the streams of Cadillacs and BMWs, the trucks taking furs to Macy's and Texan beef to the trendy ethnic restaurants in Harlem, the coloured populations will vanish.

It might be, as some say. that in the Sixties progressive liberal legislation strip- ped them of their pride, that dole and single-parent allowances created a fertile soil for the idle teenager to leave home and experiment in drugs. Others like to point to disastrous schools that sought out failure among blacks and, under the guise of liberal concern, made a white empire out of its remedy. Whatever it was, the blacks and Hispanics are on their own now. There is nothing, even if it wanted to, that white America can do. Any solution must come, as with all addiction, from the hearts of the victims, not their keepers. In the past it was in the absence of help that the great epics of successful immigration were writ- ten — by the Jews, the Irish, the Poles, the Greeks. For the Puerto Ricans, and the blacks, this may be the moment. If not, they are finished.

Previous page

Previous page