The Prospect Before Us

By RICHARD ROSE Ttin ups and dcmsns of the parties at individual by-elections tend to obscure the long-range significance of trends in voting behaviour. One Orpington, one Derby North or one Brighouse and Spenborough, a Conservative gain, does not make a general election result.

Taken in isolation, the result at Derby North hardly offers a plausible guide to the next genetal election. If repeated nationally, it would mean' a massive protest against all three parties, with the greatest abstention of voters since the introduction of the.secret ballot. Labour would have a large majority in the House of Commons, but only' 40 per cent. of the popular vote, and the active support of only one-quarter of the electorate.

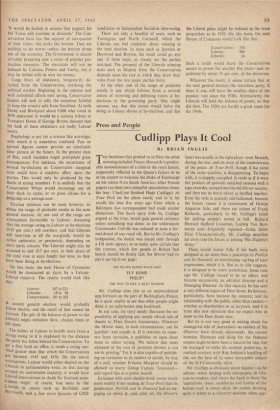

A better indication of electoral trends are the average results at the twenty-nine by-elections in this Parliament. Their most striking feature is the clear movement of voters away from both the Conservative and Labour Parties: BY-ELECTION TRENDS, 1960-62

Conservative

O W v1 0 0% ci ,--.

=

U E

0

0 ' ft:

Labour

, 0all .r1 > 0Cr,

0 •—• .0 76 0 sa U E < ,.. ,1..

Liberal

E.) 4-+ tr■

0 >

6 CI) S

>

1960 43.3

—7.6 34.7 --8.t)

24.3 +7.4 1961 35.8

—15.8 38.5 —5.5

25.2 +8.3 1962 26.9 •

—11.8 --- 45.0 --3.1 - —

30.3

.+13.4

Avgc. change

—13.2 —5.9

+9.2

___ ____ .-- • (Note: These columns are not complementary because of some straight and four-cornered fights,) Labour seems to be moving forward only because it is going backward more slowly than its Conservative competition. Since last autumn Labour has begun to brake its decline, while the Conservative descent has • been accelerating. Only the Liberals have been climbing, and at an.

accelerating pace. • By-election figures show that the Liberal new supporters vary greatly,: depending upon the time, the place and the circumstances. At by. elections in 1960, they appeared to come more from Labour than from Conservatives in seats such as Mid-Bedfordshire and Ebbw •Vale. Since Moss Side, the trend has appeared to reverse. Liberals appear to draw more Conservative than Labour voters to their standard because they more often stand in Conservative than Labour seats, and draw a fair cross-section of the com- munities there. The Nuffield analysis of the last election confirms this pattern. Then, Liberals appeared to draw on average forty-five ex- Labour voters for every fifty-five ex-Conserva-; tives.

The task of projecting by-election results into the next general election is complicated by factors other than the Liberals. By-elections normally exaggerate the strength of the Opposi- tion, whether. Conservative or Labour. In 1950-51 there was a 4 per cent. swing to the Conservatives at by-elections, but only a I per cent. swing to them at the 1951 general election. During the last Parliament there was a 5.1 per cent. swing to Labour, but at the 1959 election the Conservatives regained all their lost support and then some. Liberals normally do well at by- elections and lose some of their new-fotind support at general elections.

As Len Williams recently told party workers, 'It would be foolish to assume that support for the Tories will continue to diminish.' The Con- servatives have lost the support of one-quarter of their voters; this looks like bottom. They are unlikely to do worse—unless the bottom drops out of the economy. The Government is almost certainly preparing now a series of popular pre- election measures. The electorate will not be seduced by Colman, Prentis and Varley, but it may be bribed with its own tax money.

Large blocs of abstainers, temporarily de- tached from the Conservatives, overhang the political market. Beginning in the autumn and with redoubled efforts next spring, Conservative leaders will seek to rally the sometime faithful to keep the country safe from Socialism. At both Derby and Blackpool about 9,000 who voted in 1959 abstained. It would be a curious tribute to Transport House if George Brown claimed that the bulk of these abstainers are really Labour voters.

Psephology is not yet a science like astrology, with which it is sometimes confused. Past or current figures cannot provide an absolutely clear picture of the future. In the present state of flux, small incidents might precipitate great consequences. For instance, the occurrence of several by-elections in Conservative marginal seats could have a catalytic effect upon the parties. This would only be produced by the death of sitting members. It is unlikely that the Conservative Whips would encourage any of their flock to retire, or to press claims for a judgeship or a peerage now.

Election statistics can be used, however, to define the range of probable results at the next general election. At one end of the range are assumptions favourable to Labour. Assuming that the average swing to Labour at by-elections (3.65 per cent.) will continue, and that Liberals will intervene in all the marginals, would be rather optimistic, or pessimistic, depending on one's party colours. The Liberals might also be assumed to add 13.7 per cent. to their share of the total vote in seats fought last time, as they have been doing at by-elections.

On this basis, the next House of Commons would be dominated de facto by a Labour- Liberal majority. The results would look like this: Labour: 307 to 321 Liberals: 18 to 28 Conservatives: 281 to 302 A second general election would probably follow shortly, and the result of that cannot be forecast. The gift of the balance of power to the Liberals might stiniulate them, chasten them or kill them.

The failure of Labour to benefit more from a strong swing to it is explained by the distance the party has fallen behind the Conservatives. To get a firm hold on office, it needs a swing one- third greater than that which the Conservatives got between 1945 and 1950. On the above assumptions, Labour would either depend on the Liberals in parliamentary votes, or else, having scraped an unworkable majority, it would have Liberal interventions to thank for fourteen seats. Labour might. of course, lose seats to the . Liberals in places such as Rochdale and Merioneth, and a few more because of CND candidates or Independent Socialists intervening.

There are only a handful of seats, such as Torrington and North Cornwall, which the Liberals can feel confident about winning at the next election. In seats such as Ipswich or Heywood and Royton, the result could go any one of three ways, so closely are the parties matched. The prospect of the Liberals winning seats such as Skipton from the Conservatives depends upon the rate at which they draw their votes from the two major parties there.

At the other end of the range of probable results is one which follows from a normal return of wavering and defecting voters at by- elections to the governing party. One might assume, say, that this return would halve the swing to Labour shown at by-elections, and that the Liberal gains might be reduced in the same proportion as in 1959. On this basis, the next House of Commons would look like this: Conservatives: 336

Labour :

280 Liberals: 14 Such a result would leave the Conservatives secure in power for another five years—and re- pudiated by about 55 per cent. of the electorate.

Whatever the result, it seems certain that at the next general election the victorious party, if there is one, will have the smallest share of the popular vote since the 1920s. Alternatively, the Liberals will hold the balance of power, as they did then. The 1920s are hardly a good omen for the 1960s.

Previous page

Previous page