Less intervention, please!

Michael Jefferson IS is the second of a number of articles under the general title, Inflation and Stabilisation, each „,-,_,hich suggests a prognosis and cure for the nation's immediate financial ills. The contributors urawn from leading economists representing the major schools of economic thought.

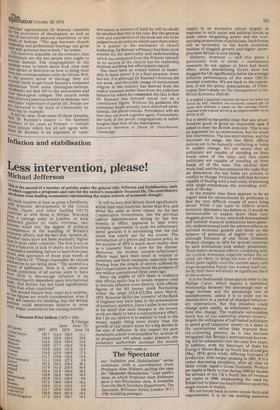

A/1 items MY Work requires at least as great a familiarity Ztith economic developments in the United Ste economic Japan, and other leading OECD i`,.ntries as with those in Britain. Watched Vul a vantage point in London, or with feat glance on visits overseas, two incatures stand out: the degree of political umPetence in the handling of Britain's • int.] true affairs; and the fact that, despite all, th ation rates have not been markedly higher rn„4,11,in most other countries. The first is not so or-ii a function of lack of ability as a function erre)coessive meddling, failure to learn from past °ts, and ignorance of those wise words of 1Ciri Charles II: "Things impossible do excuse selves in not being done." The second is a of bafflement. How is it, when most dok'sh politicians of all parties seem to have ecorle little to discourage inflation in an trall°my heavily dependent upon international '4'oue, that Britain has not fared significantly ..:se than other countries? so 1,12ts second feature may come as a surprise, ti.„ e figures are worth consideration, even if ''re are reasons for thinking that the British zsiitian could deteriorate relative to most er Major countries in the coming months: Consumer Price Indices (1970 = 100) % Change June June '73/ 1972 1973 1974 June '74

It will be seen that Britain fared significantly worse than nine countries, better than five, and about the same as three others. As the last Conservative Government, like the previous Labour Administration during its last few months in office, appeared to take every available opportunity to push the inflationary spiral upwards it is astonishing that the end result was nearly par for the course. The introduction of a prices and incomes policy in the autumn of 1972 is much more readily seen as a cosmetic than a cure for the disease. Moreover, the modest counter-inflationary effects must have been small in relation to monetary and fiscal measures, especially those flowing from the attack of nerves suffered by the Conservatives as they faced the prospect of one million unemployed three years ago. Since the middle of 1973 there is evidence that official policy has in certain respects tried to restrain inflation more directly, with official figures of the MI money stock fluctuating within the range £12.8-£13.2bn since March, 1973. However skilful the 'corsetry' of the Bank of England may have been in the presentation of monetary statistics, Dave Laidler is not alone in his belief that such changes in the money stock are likely to have a contractionary effect. But I do not believe it is realistic to look to the money supply rising more slowly than the growth of real output alone for a big decline in the rate of inflation. In this respect the pure monetarist school oversimplifies for, as most of its proponents will admit under pressure, the monetary authorities increase the money supply to an excessive extent largely in response to such social and political forces as trade union bargaining power and the votecatching propensities of politicians. Such forces will be secondary to the harsh economic realities of sluggish growth and higher unemployment Britain is now facing.

Hitherto, however and this point I particularly wish to stress stabilisation measures do not appear to have had much effect, while destabilising forces have not dragged the UK significantly below the average inflation performance of the main OECDmember countries. We are back to the conclusion, if not the policy prescriptions, of Christopher Dow's study on The Management of the British Economy 1945-60: It is indeed a question whether we have not been too clever by half; whether the economy cannot get on quite well without a hand on the steering wheel; whether even a good driver is an improvement on no .driver at all.

For it seems to me pretty clear that any driver, however good, is given an impossible task if asked to steer the British economy. This is not an argument for no intervention, but for much less intervention. The less intervention, and the narrower its range, the less likely official policies are to be mutually conflicting or liable to sudden change. We are aware that all politicians are capable of standing on their heads some of the time, and that some politicians are capable of standing on their heads all of the time. The smaller their work-load, and the less extensive the tasks they set themselves the less liable are policies to conflict or change. Politicians will then be more capable of dealing with a real crisis; of pursuing with single-mindedness the overriding prob lems of the day.

At the present time there appears to be an urgent need for retrenchment by politicans to face the very difficult couple of years lying ahead. While It. am loath to believe severe economic depression lies before us, it would be unreasonable to expect more than very sluggish growth. In my view both international and national research institutions have generally underestimated both the adverse effects on national economic growth and those on the balance of payments of higher oil prices, although forecasts of real Gross Domestic Product changes in 1974 for several countries by such institutions look unduly pessimistic. These macro-economic effects, combining with the cyclical downturn expected before the oil crisis, are likely to bring the rate of inflation down quite rapidly once the current salary and wage-bargaining frenzy has worked itself out, for by then there will surely be significant slack in the economy.

It is not fashionable these days to refer to the Phillips Curve, which depicts a statistical relationship between the percentage rate of wage increase and the percentage rate of unemployment, unless it is to point out its obsolescence in a period of changed inflationary expectations. But this situation could change quite rapidly, as inflationary expectations also change. The euphoria surrounding North Sea oil has somewhat abated recently, despite the willingness of half-baked politicians to spend good taxpayers' money on a share in the uncertainties rather than improve their tax-collecting powers, as it has become recognised that Britain's international borrowing will be substantial over the next five years. In addition, even the Secretary of State for Energy's 'Brown Book' on North Sea oil and gas (May, 1974) gives wildly differing forecasts of production, with output peaking in 1981. It is a rather depressing possibility, after all, that on likely trends .Japan's Gross Domestic Product per capita is likely to rise during 1980 by double the amount of the UK's North Sea oil revenue per capita in 1980, emphasising the need for Britain not to place too much reliance upon this single source of wealth.

We are forced back to some simple facts and requirements. It is no use seeking panaceas which are liable to have all the characteristics of the will-o'-the-wisp. It is no use complaining that we do not invest enough in plant and machinery and buildings, when we use what we have inadequately and labour productivity is so much higher in some other advanced industrial nations, where working hours are shorter and the pay higher. It is no use squeezing the middle classes in favour of the aspirations of others, since this is a recipe for even less efficient management and productivity as well as for political instability and bad national morale. It is no use trying to avoid the fact that inflation can be cured only during a period of higher unemployment, although the relationship between changes in earnings, unemployment, and inflation may alter over time — as can the significance of particular rates of unemployment.

But inflation cannot go on for ever at annual rates well into double figures in a mature economy without either democracy going to the wall or inflation falling with a downturn in the business cycle. Inflation rates have, after all, fluctuated wildly — if about a slowly rising trend — in the post-war period. Even in a mixed economy, with Mr Benn and his henchmen running amok, the built-in stabilisers will continue to come into operation. Before they do, however, politicians are liable to have caused the cyclical fluctuations to be much sharper than they would otherwise have been.

This may not place Britain in a worse position in the inflation stakes than some other countries, but it is difficult to believe the situation would not have been better without the constant intervention's of the politicians. The result of less intervention would be wider fluctuations in unemployment, against which would be balanced lower inflation and higher economic growth in the longer run. Higher unemployment more often, but greater prosperity to handle that problem more generously as well as providing substantial benefits to everyone else.

•

Michael Jefferson, the economistand social historian, has been manager of an economic consultancy and Deputy Director of the Industrial Policy Group. He is now Head of General Economics in a leading international oil company

Previous page

Previous page