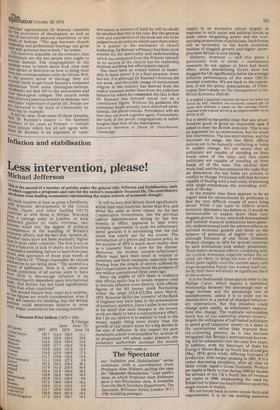

The Church

The Ramsey years

Edward Norman

During the nineteen-sixties the English churches appeared to undergo a considerable collapse of confidence. There was a crisis both of values and of beliefs. It came suddenly — following a decade of some buoyancy, when religious institutions appeared reasonably confident to meet the requirements of a changing society. The collapse, though sudden, ought not to have been surprising, however. In effect church leaders were merely reflecting the intellectual fashions and the moral illiteracy of the intelligentsia of which they were a part. Despite their rush to 're-interpret' the Bible, and for all their new appraisals of the premises of the humanist doctrine of man, the theologians simply jerked about, like grotesque marionettes, in any direction the hands of contemporary fashion appeared to direct. The disintegration was the more astonishing because it was contrived by such a small minority within the church.

Agnostic theology acquired instant prestige — there were very few theologians of any standing who did not join the rush down the steep slope. The bishops of the Church of England wavered. A few embraced the new radical theology with something like secular ecstasy; most shuffled into an unsteady and unconscious parody of the liberal conscience, acclaiming indifferent compromises as triumphs of adaptation to the modern world. The men and women in the pews, and the huge majority of ordinary believers in this country, who do not go to church but who are anxious to preserve a Christian identity, were unable to comprehend what was going on.

Occasionally writers in the national press urged church leaders to speak out against the moral calamities of the 'permissive society.' They were unheeded. The leaders of church opinion seemed to regard humanist morality as a mature recognition of the 'adulthood' of the human race; for ordinary people, the price for listening to them was paid in the currency of broken lives and great personal distress. In the nineteen-sixties the churches were offered the chance to heal the self-inflicted wounds of humanity by bringing the mysterious presence of Christ to the knowledge of their people. It was the duty of the churches to direct men to the urgent pursuit of their eternal destinies, to lay aside the rubbish of human material endeavour and to reach out, instead, to the first intimations of the unchanging values of the unseen world. Alas, the church was blown away by ridiculous little gusts, and the great chance was lost. In the parishes, the local clergy did what they could, often with very real heroism and sacrifice. For it was a crisis of leadership which deflected the church from its proper course, not a sickness of the body as such.

Unenviable, indeed, was the plight of the man charged with guiding the church through all this. In 1961 Dr Michael Ramsey became Archbishop of Canterbury, the office he relinquishes next month. In a book of essays just published *he makes it clear that he had not expected the theological uproar. There was, he writes, "little awareness that a theological upheaval was on its way." But Dr Ramsey agrees that, once it had begun, it "was a rest for leadership'." In his book he does not' probe the matter of leadership much further. Had he done so, he would perhaps agree that he had, during his years in office, been confronted with two alternatives.

Canterbury Pilgrim Michael Ramsey (SPCK £3.25) Put at their most extreme, he could have led the church in adhesion to its 'traditional' claim to a unique explanation of human life; to have, in effect, gone to the much-paraded intellectual inquiry of the times and turned it down flat. That may, to some extent, have continued the stability of Archbishop Fisher's Primacy; the radical theologians would, of course, have raised a terrific howl; but then they did that anyway. It is a sort of personal need they have. Dr Ramsey could, on the other hand, have given direct encouragement to the new theology; with his own distinguished academic pedigree he could, to put it vulgarly, have cornered the market.

It might be supposed that an Archbishop of Canterbury does not have the power to do either of these two things. But that would be mistaken. He has not, perhaps, the power, but he very definitely has the influence. In fact Dr Ramsey opted for a middle course. "The new Christian humanism," to which he looks, -will blend the supernatural faith concerning God and Man with an openness to the sciences, knowing that, amidst all the tensions between imperfect apprehensions of Truth, all Truth is of God and no Truth is to be feared." Dr Ramsey is a liberal; he is also an academic theologian. Any other behaviour on his part would have been out of character.

His formula has its difficulties, not too many of which have been allowed to get in the way. Holding the balance between two quite clearly alien spiritual psychologies is a demanding matter. So is the free and uninhibited exploration of 'truth' at a time when the intellectual world is showing itself capable of promoting seemingly any absurd doctrine, and when fashions of thought come and go with a staggering rapidity. This, indeed, is a perilous exercise in any condition: for the Church of England, whose present hold upon intellectual quality is not all it might be, it requires superhuman powers.

Now superhuman powers are exactly what churches are most able to call upon. The truth is that the radical theologians aren't really sure if they exist. It is an irritating impasse. The point is a disagreeable but necessary one. There is very little awareness inside the church of how slight its intellectual talent has become. In the hot-house atmosphere of the academic theologians, of course, the declamation of 'critical' attitudes is commonplace. But no one actually is critical. During the last ten years the theologians and ecclesiastical pundits have jumped on and off so many bandwagons that their brains must be literally addled by the sheer effort. They are far too addicted to ideas; far too impressed by intellectuals; far too little aware that unless the pursuit of the knowledge of God is immediately related to a life of prayer and self-discipline then the result will be — well, what it has been.

Dr Ramsey's unhappy formula reflects the generosity of his nature; he makes too charitable an assessment of the capabilities of some of his colleagues. He is himself among the very few who have, in their own lives and learning, actually achieved the balance he advocates. For so many others, in the world of academic theology, no balance has resulted at all: only exotic and transient growths,-epherneral enough to prove convenient for their practitioners, but solid enough to tangle the faith of simple believers.

The notion that "no Truth is to be feared" is perfectly sound when really applied to 'Truth.' But what about all the intellectual rubbish

Spectator October 26 1974 which is 'Truth' only in the eye of each beholder? Men are capable of believing just about anything if it is wrapped up in the language, and ,presented in the images, of immediate appeal. There is nothing peculiarly sanctified, or special, about intellectual endeavour. In fact the gullibility of intellectuals is notorious. There is no sort of human nastiness which does not have, or has not had, the backing of intellectual opinion. Dr RamseY does see this. "Man can advance wonderfully in scientific knowledge and yet remain selfish, insensitive, and cruel," he writes. But it is also the case that truth cannot, in any ordinarY sense, be pursued for its own sake as Dr Ramsey supposes. For in practice men assimilate knowledge according to a scale of values determined by their initial expectations. If the world of secular humanism is explored by minds soaked in secular humanism, the result will not be a revelation of the greatness Of God's love. Knowledge is not neutral. There is no body of objective reality just waiting to be discovered by men of unclouded vision and unprejudiced outlook. But Christianity has a prior knowledge of God, transmitted in a mysterious tradition in the lives of those in whom Christ has been present. And while it is certainly right to ensure that the faith is not attached by some accident to a false cosmology, or a wrong ethical code, nothing ba, t disaster will -follow the attempt — now widelY being made — to show that the Christian view of human life is not unique and sufficient. It ls not 'traditional' spirituality, but contemporarY radical theology, which is the agent whereq Christianity is being identified with cultural accidents and false explanations of the world. Christianity is not — emphatically not — arlf 'open' system of values, "an adventure a, freedorh" (to use an unfortunate expression or Dr Ramsey's); an agenda still relatively blank, awaiting the hand of 'modern knowledge' ta write down the items. In his collection of essays, Dr Ramsey blaMes himself for the `initial error,' for `reaction,' l9 criticising Honest to God when it was publisheu by the then Bishop of Woolwich in 1963: It is a pity he now feels this. For that book, trivial itself, began the opening of a chasm scepticism into which has fallen the faith ai very many who thought they were -thinking far themselves.' It has become fashionable in tl,le church to say that theology of that sort mere'Yf spoke frankly to the 'honest' doubts of men o integrity. It is supposed, also, that this is the first age in which men really have soundlYbased reasons for doubting the faith: hence the, need for a 'mature' approach to honestly-hela doubt. Not only does this mistaken view cla considerable injustice to the atheism an scepticism of preceding generations, it also sets. far too high a value on the intellectual discoveries of this one. But it is a view which has acquired a sort of orthodoxy within the leadership of the church. It is a shaming paradox that the new radical theology, 500't0 defended on the ground that it makes Christianity more easily acceptable to modern men' is more often, in reality, a testimony to the. excited attempts, by those who have slipPe,° from their spiritual moorings, to persuaae themselves that it is still true. The question of leadership recurs in 1", Ramsey's essay on 'Church and State England,' in which, as one who would grieve "to wake up and find that the Englis establishment was no more," he argues for greater church freedom from state control in such matters as episcopal appointments. There is much to be said for that, too; though it unfortunate that Dr Ramsey apparentu regards the establishment of the church as a e question of 'privilege,' unwarranted in thes days of parity, and not, as in fact it is, III obligation of service placed upon the chura" often to the detriment of its own efficiencY,E provide the Christian foundation to the balJe politic which the great mass of ordinary PO? still believe desirable. While considerrab 7Piseopal appointments Dr Ramsey contends or the promotion of theologians, as well as men g oi exclusively pastoral experience, to the ;bench of bishops. "The gap between church leadership and professional theology can grow Only With grievous loss to both," he writes. • It is, however, arguable, on the contrary, that intellectuals are the last people who ought to become bishops. The congregations in the Parishes want to know about God: they seek Clear advice or direction on how to bring their lives into correspondence with the Divine Will. In the present mood of theology they are scarcely likely to get much beyond a tempered agoOsticism from some theologian-bishops. Academics are best left to the universities and their theological colleges. The church needs 111.erl of strong pastoral instinct as bishops; men WIth Years' experience of parish life. People are ;`,c3t Converted to the truth of Christianity by '"eas, but by example. that Will be clear, from some of these remarks, t "at Dr Ramsey's essays his farewell summary of his years as Primate contain sQ°.rue notions which not all will agree with. Since Dr Ramsey is an exponent of 'open'

discussion in matters of faith he will no doubt be satisfied that this is the case. But the general tone and contribution of the book are not to be judged from an analysis which uses them solely as a pointer to the mechanics of church' leadership. Dr Ramsey's Primacy has been most notable for the spirituality and understanding which has emanated from the Primate himself. In no section of the church has his leadership inspired anything but affectionate regard. Has there been an overall failure of leadership in these years? It is a final paradox: there has not. For although Dr Ramsey's formula did not work, and the public, image of institutional religion in this country has derived from the radical excesses rather than from the judicious balance for which he contended, the fact is that Dr Ramsey has himself stood out as a conciliatory figure. Without his guidance the enterprise might actually have dissolved away. Instead, the pieces remain. Providence will see that they are stuck together again. Fortunately, the faith of the parish congregations is rather tougher than that of the theologians.

Edward Norman is Dean of Peterhouse, Cambridge

Previous page

Previous page