What Do I Really Mean?

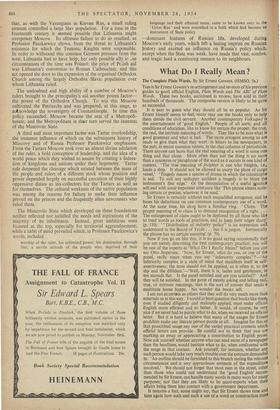

The Complete Plain Words. By Sir Ernest Gowers. (HMSO. 5s.) THIS IS Sir Ernest Gowers's re-arrangement and revision of his previous guides to good official English, Plain Words and The ABC of Plain Words. These two books, acclaimed in review, have sold in their hundreds of thousands. The composite version is likely to be quite as successful.

It is easy to guess why they should all be so popular. As Sit Ernest himself seems to feel, many may use the books only to help them deride the civil servant. Another contemporary Volksspiel is the ascertainment of 'good English.' People of all sorts, and all conditions of educatiqn, like to know for certain the proper, the true, the real, the intrinsic meaning of words. They like to be sure what is good grammar and yvhat is bad. The more arrogant among us are ready to give them what they want: in letters ta the newspapers, in the pub, in senior common rooms, in the chat columns of periodicals. There anyone can learn that the real meaning of a word is some one thing and that alone. More often than not the thing is no more than a synonym or paraphrase of the word as it occurs in one kind of context. 'The true meaning of freighter is one who freights, i.e., loads a ship. It should not be allowed to usurp the place of cargo vessel." Tragedy means a species of drama in which the catastrophe is sad. To call any unhappy accident a tragedy is to blunt the instrument's fine edge.' Or the denunciation of a useful practice will end with some impatient utterance like 'This phrase means noth- ing certain or precise, wherever it be used.'

Sir Ernest is certainly without such unqualified arrogance, and he bases his definitions on one common contemporary use of a word. At the same time, his dial have a familiar ring. Claim. The proper meaning of to claim is to demand recognition of a right. . . The enlargement of claim ought to be deplored by all those who like to treat words as tools of precision, and to keep their edges sharp' (p. 110). ' "Distribution of industry policy" is an expression well understood in the Board of Trade . . . but it is jargon. Intrinsically the phrase has no certain meaning' (p. 79).

Now if you go on like this, it is no good saying occasionally that you are merely describing the best contemporary practice; you will be one of the experts in 'What Do I Really Mean?' before you can say Otto Jespersen. 'Now, Sir Ernest, what do you, as one of the panel, really mean when you say "inferiority complex"?'—'An inferiority complex is a state of mind that manifests itself in self- assertiveness; the term should not be applied, as it often is, to the shy and the diffident.'—'Well, there it is, ladies and gentlemen, in ten seconds flat. Is the panel satisfied and are you satisfied?' And they will be satisfied. In the game of merely asking and telling real, true, or intrinsic meanings, that is the sort of answer that sends a multitude home happy. No wonder the books sell. I am not as certain as others that they will do very much more than entertain us in this way. I would at least question that books like these, even if studied diligently and zealously applied, must make official English more efficient and so better. It would, of course, be very nice if we never had to puzzle what to do, when we received an official letter. But it is hard to believe that many of the usages Sir Ernest prohibits make any literate person puzzle at all. Imagine for this or that proscribed usage any one of the varied practical contexts which official letters can provide. Be careful not to think that you are marking an essay or appreciating a contribution to English prose. Now ask yourself whether anyone who can read more of a newspaper than the headlines, would hesitate what to do, when confronted with the usage in that context. Ask yourself, for instance, whether any such person would take very much trouble over the estimate demanded in: 'An outline should be furnished to this branch stating the relevant circumstances and a very approximate estimate of the expenditure involved.' We should not forget that Most men in the street, other than those who could not understand the 'good English' recom• mended by Sir Ernest, can handle many words in many ways for manY - purposes; nor that they are likely to be quasi-experts when their affairs bring them into contact with a government department. It remains a fact, some might say, that Sir Ernest shows time and time again how such and such a use of a word or construction must 4,produce obscurity. But the fact is that Sir Ernest often creates Obscurities where there are none. As long as we understand a word or phrase, we do not worry whether it is paraphrasable by another Word or phrase. Sir Ernest, though his observations show that he understands many a use of a word, decides it is obscure if certain Paraphrases are possible and others impossible. For .example, if in the popular phrase other must be the synonym of alternative, Sir Ernest implies that the phrase is obscure, but wherever the paraphrase can be freely choosable or something like that, he would assert its crystal clarity. People who are offered alternative accommodation do not doubt what they have to do. It is curious how, knowing present-day English practice so well, Sir Ernest can say that much of it is not just unpleasant, but a hind- rance to rapid and clear understanding. The answer is, perhaps, to be found in his views about the purpose of writing. 'Writing is an instrument for conveying ideas from one mind to another.' If you say things like this, you will be tempted to ask: What is the idea behind this paragraph, sentence or word? A paraphrase or synonym Will present itself as an answer. Because you have this answer to this question, and you like the answer for aesthetic or personal reasons, You can easily think that the paraphrase or synonym is nearer the idea and so less obscure than the original form. You will all the more readily think this when the new uses of a form suggest a novel pam- Phrdse or synonym, e.g., other for alternative; that is, a phrase or Word familiar enough, btu novel as the equivalent for the new use. A few passages of official' gibberish do, indeed, appear in The Complete Plain Words, but I have suggested that much of what Sir Ernest bans does not necessarily end in this kind of nonsense. It is, too, very easy to make nonsense with 'plain words.' I do not argue that all the advice might be ignored; nor that it is all so completely unnecessary that it will produce no change what- ever in Official English. The writer is told to avoid any high degree of syntactical complexity, and any large measure of periodic sus- Pension. This is the sort of advice you can easily take, and which, Indeed, your correspondents will force you to take. To follow it does help towards getting people to do quickly what you would like. Sir Ernest's book would best be used in schools and universities. If students followed his recommendations without worrying about the reasons for them, they would more often write as their tutors desired. But a student essay is not an official letter.

DAVID SIMS

Previous page

Previous page