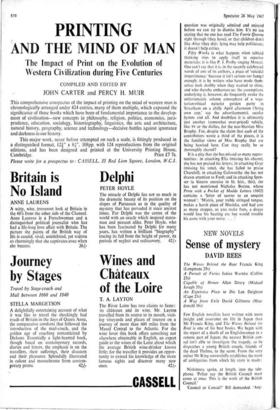

One awful example we could do without BOOKS

MARTIN SEYMOUR-SMITH

One naturally assumes that a book of approxi- mately 60,000 words which sets out to demon- strate the dispensability of, among other things, Beowulf, The Faerie Queene, Hamlet, the works of Jonson, Mon Flanders, Tom Jones, Gray's Elegy, The Scarlet Letter, Pickwick Papers, Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, Moby Dick, the poems of Whitman and Hopkins, Alice, the works of Hardy, Esther Waters, To the Lighthouse, and the works of T. S. Eliot, Faulkner and Hemingway, will turn out to be a joke, a squib at the expense of pretentious- ness or conventional pedagogic attitudeS of over-reverence and under-regard. After. all, Stephen Potter's The Muse in Chains is now thirty years old; we could do with a new ver- sion. A photograph of the authors—Miss Brigid Brophy, Mr Michael Levey and Mr Charles Osborne—on the back of the dust- wrapper, smirkingly posing as enfants terribles in faded sepia, strengthens this impression. This, one thinks as one opens the book, might be fun.

But Fifty Works of English Literature We Could Do Without (Rapp and Carroll, 2Ss) is not, as its price reminds us, supposed to be at all funny. Even the authors' jokes are not sup- posed to cause laughter, but (presumably) epater le bourgeois: the Bible is not listed only because translations have been excluded. And the tone of the preliminary `address to the reader,' although couched in an unracy, cliché- ridden amalgam of office-girl slang and boy- scoutese, is determinedly and pompously earnest: `Before you let fly with a scream at our iconoclasm, pause and play fair: do you really like, admire and (most important_ cri- terion of all) enjoy the works in question, or do you merely think you ought to?'

Fifty Works is 'a start' at the task of `weeding' English Literature: the authors are 'moved' by their 'sense of injustice done alike to treat authors and to the public' by 'pundits.' The principle upon which it has been written; they claim, was enunciated by Coleridge in his re- mark, 'Praises of the unworthy are fel/ by ardent minds as robberies of the deserving': thus, `if you will go so far as actually to read our text, you will find that quite a lot of it consists of literary appreciation'; 'We have been at pains both in this . . . address and throughout our text to indicate which the blooms are for whose sake we want to clear the weeds.'

Clearly, the authors think that some of the so-called classics have been inflated at the ex- pense of other, better works. Of what, then, does their 'quite a lot of literary appreciation' consist? Who, according to their `ardent minds,' are the 'deserving' writers who have been so unjustly robbed? Marlowe, Shakespeare, Web- ster, Donne, Crashaw, Marvell, Pope, blenry James, Shaw, Jane Austen, Thackeray, Gibbon, George Eliot, Chaucer, Keats, Beaumont, Flet- cher, Milton, Congreve, Vanbrugh, Homer, Montaigne, Bacon, Sydney Smith, Edward Lear, George Eliot, Browning, Heine, Sophocles, Proust, Cleland, Wilfred Owen, Coleridge, Peacock, T. H. White, Gertrude Stein. Which of these authors, one asks, has not had his

due? And which of the listed works has robbed him of it? The answer to both questions is, unequivocally, 'none.'

The authors' depreciations are similarly de- void of critical content. They claim in their `address' to be fighting to challenge, against `the whole weight of received opinion,' the views that `force our children into philistinism.' But Fifty Works—an exhibitionistic pseudo-Shavian joke that has gone absurdly wrong, owing to the authors' humourlessness, casually sketchy knowledge of their subject-matter and refusal to think hard—is in itself aggressively philis- tine. It is boorishly intolerant without being original or witty; it sets out to destroy `received opinion' without knowing or understanding it; it disguises a set of private prejudices and opinions as a critical view of English Litera- ture; it is ill-mannered and its bad taste is dreary, unredeemed by brilliance or any of the insights of eccentricity. Usually the authors are content with straightforward abuse, couched in hackneyed terms. Whitman is `a garrulous old bore,' in which `le style is undoubtedly thomme: Favoured adjectives are `stuffiest,' `worthless,' awful' and `unspeakable.'

One could not, without voluntarily regressing to an adolescently counter-abusive state of mind, `argue' with such strictures as I have quoted; they are not strictures but slabs of third-rate invective, and are philistine because they introduce thoughtless vulgarity and self- conceited opinions into an area of discourse

which should properly be free from such things. All one can, ido here is to point out as an Awful Examhle the elementary critical errors into which the three authors have fallen. Their basic error is a glaringly consistent failure to observe the general, commonsense principle sometimes known as psychic (or aesthetic) distance: in order to appreciate or respond to a work of literature, there has to be a gap between the reader's per- sonal needs and prejudices and the work itself. But the authors do not like cruelty, particularly to animals, any form of religion, particularly Catholicism, authoritarianism or the mediaeval past. So Moby Dick is a bad book (cruelty to animals), and The Scarlet Letter (which, with breathtaking ignorance or insensitivity or both, they state is not ironic) is bad because it is - `puritanical' and about human cruelty. Hop- kins's poetry is `absurd' because he was a Catholic. Using Professor Wilson Knight's well- known and interesting characterisation of Hamlet as the selfish villain of the play as a starting-point, they proceed to condemn the play itself on this ground. Faulkner's novels are bad because of their subject-matter. Kipling is no good because . . . good heavens! He was an imperialist! In this respect as in others, Fifty Works would make an admirable pre-`0'

. level textbook of how not to approach literature.

Probably the most revealing lapse in Fifty Books is the all-out attack on Ben Jonson. When the authors say that his verse is laboured, one remembers, and more than likes, admires and enjoys the famous lines I, that spend half my nights and all my days, Here in a cell; to get a dark pale face,

To come forth worth the ivy or the bays, And in this age can hope no other grace— Leave me! There's something come into my thought, That must and shall be sung high and aloof, Safe from the wolf's black jaw, and the dull ass's hoof.

One has to wonder whether the authors have actually read Jonson. Can anyone be so crudely insensitive? But their cocky swagger conceals an almost touching naivety, ineptitude and confusion about poetry.

Not only Jonson but also Spenser wrote monotonous verse! And although Housman is on their list, they believe in the 'ravishing non- sense' theory of poetry—a highly academic Eng. Lit. view, if only they knew it (though Housman had private reasons for holding it): thus, Xanadu (sic) is `a beautiful opium-image,' and contains no 'profundities.' Is it pathetic or bathetic, or both, to find that the very writers who purpose to educate us out of our literary philistinism, and who use a remark of Coleridge's (not, incidentally, in a way he would have approved) as their 'principle,' are ignorant of everything written about him after Livingston Lowes's well-known study, The Road to Xanadu (1927)?

Of course we all feel, as individuals, that there is something wrong with literary taste —at both popular and academic levels. But no writer who has lasted as the majority of those listed here have lasted can be dismissed without critical consideration, but with a few ill-chosen abusive adjectives, and on the basis of a familiar cluster of Edwardian prejudices. We have to understand why the writer is question was originally admired and enjoyed before we can try to dismiss him. It's no use stating that no one has read The Faerie Queene right through (they have), or that children don't like Alice (they do): lying may help politicians; it doesn't help critics.

Fifty Works is what happens when tabloid thinking tries to apply itself to superior materials; it is like P. J. PrOby singing Mozart. One can't say that it is, in the recently celebrated words of one of its authors, a piece of 'suicidal impertinence,' because it isn't serious (or funny) enough; it is by writers who have made them- selves look shabby when they wanted to shine, and who thereby embarrass us; the assumptions underlying it, however, do frequently evoke the unfortunately solemn atmosphere of a vege- tarian-ethical naturist garden party in Streatham on a chilly April afternoon ('bring own cup,' say the advertisements), secular hymns and all. And doubtless it is ultimately just another (somewhat over-priced) vehicle, like ry or the dailies, for the neo-Shavian Miss Brophy. For, despite the claim that each of the contributors wrote a third of the pieces, it is the familiar views of Miss Brophy that are being hawked here. Can they really be so thoroughly shared?

It is a pity that she has missed so many oppor- tunities: in attacking Elia (missing his charm), she has not praised his letters; in attacking Gray (missing his tone), she has failed to praise Churchill; in attacking Galsworthy she has not drawn attention to Ford; and in attacking Spen- ser (a bizarre exercise in lit. hist., this), she has not mentioned Nicholas Breton, whose Poste with a Packet of Madde Letters (1602) contains a 'letter of scorne to an unquiet woman': 'Mistris, your treble stringed tongue, makes a harsh piece of Musicke, and had you as many stoppes, as you make frets, a dogge would lose his hearing ere hee would trouble his eares with your noise. . .

Previous page

Previous page