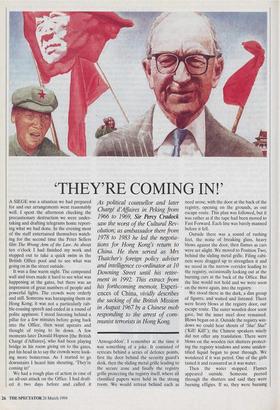

'THEY'RE COMING IN!'

As political counsellor and later Charge d'Affaires in Peking from 1966 to 1969, Sir Percy Cradock saw the worst of the Cultural Rev- olution; as ambassador there from 1978 to 1983 he led the negotia- tions for Hong Kong's return to China. He then served as Mrs Thatcher's foreign policy adviser and intelligence co-ordinator at 10 Downing Street until his retire- ment in 1992. This extract from his forthcoming memoir; Experi- ences of China, vividly describes the sacking of the British Mission in August 1967 by a Chinese mob responding to the arrest of com- munist terrorists in Hong Kong. A SIEGE was a situation we had prepared for and our arrangements went reasonably well. I spent the afternoon checking the precautionary destruction we were under- taking and drafting telegrams home report- ing what we had done. In the evening most of the staff entertained themselves watch- ing for the second time the Peter Sellers film The Wrong Ann of the Law. At about ten o'clock I had finished my work and stepped out to take a quick swim in the British Office pool and to see what was going on in the street outside.

It was a fine warm night. The compound wall and trees made it hard to see what was happening at the gates, but there was an impression of great numbers of people and powerful lights. The crowds were orderly and still. Someone was haranguing them on Hong Kong; it was not a particularly rab- ble-rousing speech and ended in a round of polite applause. I stood listening behind a pillar for a few minutes before going back into the Office, then went upstairs and thought of trying to lie down. A few moments later Donald Hopson [the British Chargé d'Affaires], who had been playing bridge in his room giving on to the gates, put his head in to say the crowds were look- ing more boisterous. As I started to go downstairs I heard him shouting, `They're coming in!'

We had a rough plan of action in case of an all-out attack on the Office. I had draft- ed it two days before and called it 'Armageddon'. I remember at the time it was something of a joke. It consisted of retreats behind a series of defence points, first the door behind the security guard's desk, then the sliding metal grille leading to the secure zone and finally the registry grille protecting the registry itself, where all classified papers were held in the strong room. We would retreat behind each as need arose, with the door at the back of the registry, opening on the grounds, as our escape route. This plan was followed, but it was rather as if the tape had been moved to Fast Forward. Each line was barely manned before it fell.

Outside there was a sound of rushing feet, the noise of breaking glass, heavy blows against the door, then flames as cars were set alight. We moved to Position Two, behind the sliding metal grille. Filing cabi- nets were dragged up to strengthen it and we stood in the narrow corridor leading to the registry, occasionally looking out at the burning cars at the back of the Office. But the line would not hold and we were soon on the move again, into the registry.

We stood there in the dark, a dim group of figures, and waited and listened. There were heavy blows at the registry door, our escape route. The outer wooden door soon gave, but the inner steel door remained. Blows began on it. Outside the registry win- dows we could hear shouts of `Sha! Sim!'

Kill!'); the Chinese speakers wisely did not offer any translation. There were blows on the wooden riot shutters protect- ing the registry windows and some uniden- tified liquid began to pour through. We wondered if it was petrol. One of the girls tasted it and reassured us it was water.

Then the water stopped. Flames appeared outside. Someone peered through the shutters and said they were burning effigies. If so, they were burning

-them very close and the flames were spreading to the riot shutters. We doused the shutters. But there was a lot of smoke, probably from upstairs, where the mob were in full cry. There was a pause in the attack and some blowing of whistles. We thought per- haps it was being called off, but very soon the blows began again; they were specially heavy on the steel escape door. I checked that we had someone reliable there, but there was the unpleasant thought that the door might jam. There were more flames outside and it was becoming clear that the building was on fire; smoke was getting very thick. I spoke to Donald Hopson and said we had better get the door open and get out. By this time there were cries that they were coming through the wall at the side of the escape door. We gathered the girls togeth- er and moved them up to the door. Just before it was opened I remember Donald saying that we must have an agreed ren- dezvous. We settled on the tennis court.

The door was opened. Donald went first and I followed just behind. Our immediate worry was that if the mob rushed in as we tried to get out we would all be trampled. So we raised our hands in a generally reas- suring way and said, 'We're coming out.' They stood back for a moment, then seized us. I was dragged down the steps and had a glimpse of Donald grappling with the crowd and half-strangled by his tie.

Surrender to the crowd was a strange sensation. Mixed with fear there was even a sense of relief. No more decisions. I had spent most of the day locking up, destroy- ing, making anxious provision. Now it was straightforward and out of our hands. Per- haps it was like going over the side of a sinking ship. I was swept along by the mob and beaten mainly about the shoulders and back. Someone had hold of each arm. Occasion- ally someone would hit me in the ribs. The man who had hold of me on the left kept saying, 'Bu da! Bu dal' (Don't hit him!'). It seemed to have little effect, but there were perhaps some restraints operating: the blows were painful but not crippling. There was a circle formed in the crowd and I was carried to a soap-box, where I was put up in order to be knocked down again, by the simple expedient of two men holding my arms and another hitting me in the stomach. Someone came up and bran- dished his fist in my face, asking whether I thought the Chinese people were to be tri- fled with. I did not reply: it seemed the sort of question that did not call for an answer. Someone then demanded that I say 'Long live Chairman Mao!' I remained silent and fortunately the demand was not pressed. A photographer appeared and for his benefit — I remember he seemed rather fussy and wanted lots of preparation — my head was pulled up by the hair or forced down, while the usual two men held my arms. It was difficult to decide where I was, since as soon as I tried to lift my head to look about, it was knocked down, or pulled down, to cries of 'Di tou! Di foul' Mower your head!').

I was then carried off the soap-box and the man on the left, who turned out to be a soldier, began dragging me through the crowd. Someone disputed me with him but, after a struggle, I was flung into a gate- house belonging to the Albanian Embassy, which stood directly opposite our own. Here I found four members of the staff already collected. Ray Whitney, the Mis- sion's Chinese Secretary, and Frank Hol- royd, the Administration Officer, were flung in. An army man, told off to guard us, gave us water and spoke reassuringly about our security, saying that several PLA men had been hurt trying to protect us. He made rather anxious enquiries about the number of people in the building. Were there any in the cellars?

We kept our heads down and talked a lit- tle. Despite the danger, there was an immense sense of relief that we had come through so far. I remember quoting 'Per- haps even these things it will one day be a joy to recall': Torsan et haec ohm. . . ' Vir- gil's lines on his shipwrecked mariners floating back over years in the way the Classics masters assure us they do. I also talked with Ray Whitney about the future of the Office and the need to keep our hands on the Chinese diplomats in London.

After a while we were led off by the PLA to the side-road between the Office and the Residence, where we found most of the rest of the staff, sitting or crouching against the wall, guarded by military. Donald Hopson, his head in a bloodstained bandage, was brought to join us. We were led off to a lorry, where we were concealed by standing soldiers and then driven to the diplomatic flats.

Here there had naturally been great anxi- ety as the flames rose from the Office. There had also been physical danger. Two small blocks of flats, wholly occupied by British families, were thought to be vulner- able to attack and hasty arrangements were made with friendly missions to evacuate the occupants. This operation was still in progress when a body of Red Guards burst into the compound. Birthe, my wife, recalls snatching a colleague's youngest daughter from their path and carrying her up to a top flat. There in the dark she watched from a balcony while down below the Dutch Chargé, Dr Fokkema, intervened with the 'He's a bit of an outcast. He got a good write-up in Charles's magazine.' Red Guards, arguing with them and the PLA until the intruders finally withdrew.

The Residence had been sacked; the Office itself had been burned down. There had been no fatalities, though there were cases of concussion and all had been badly bruised and beaten. It seems likely that the army had had orders to save lives; beyond that, given their equivocal position, they probably could not go.

For their part the official Chinese media acknowledged that something unusual had happened, but their account was brief. The New China News Agency recorded that 'over ten thousand Red Guards and revolu- tionary masses surged to the Office of the British Chargé d'Affaires in a mighty demonstration against the British imperial- ists' frantic fascist persecution of patriotic Chinese in Hong Kong'. It went on to say that 'the enraged demonstrators took strong action against the British Chargé d'Affaires' Office'.

The next morning we held a council of war in my study. We needed to get mes- sages to London reporting our position and reassuring them of our safety. We advised against a rupture of relations, but proposed an evacuation of women and children (a forlorn hope as it turned out). A break in relations would not only be against our long-term interests, but might also have the effect of leaving us in Chinese hands, deprived of the remaining shreds of diplo- matic protection. We were also anxious that Chinese diplomats and officials in London should not be allowed to slip out of the country, leaving us as hostages for events in Hong Kong while lacking any Chinese counterparts.

There were also urgent practical issues. We had to establish a new Office. We chose Ray Whitney's flat: it was big and he was on his own. We had to reconnoitre the ruins to see what remained and what could be saved. For safety's sake this would have to be done in non-British transport. We also had to seek exit visas for the women and children. Finally, for the record, I dic- tated a short note to the Foreign Ministry, condemning the outrage of the preceding night and reserving all our rights. Since we had no means of delivery, it went by post.

The reconnaissance party, carried in a French car, came back with good news: the strong room was intact. But this in turn posed considerable new problems: the strong room was packed with classified papers, which had to be destroyed urgently. We began by bringing back small quantities to our flats, where fortunately we still had coal-burning stoves in which they could be disposed of. But the main bulk called for more dramatiC action and, as we thought, scientific methods.

A bizarre episode followed. The Foreign Office in its foresight had provided us with a remarkable chemical compound in the form of a powder, possibly sodium nitrate. We were told that this only needed to be scattered on the files, left for a period with the doors closed and we would find a tidy pile of ashes, all secrets consumed. We fol- lowed the instructions, scattered the magic powder in the strong room and retired. Unfortunately, when we returned we found the files neatly charred round the edges, rather like funeral stationery, but still per- fectly legible. And there was a side-effect of which we had not been warned: powerful and tenacious fumes had been generated, turning the strong room into an effective gas-chamber. The only way to retrieve the documents was for each of us to wrap a towel round his face, plunge into the gas- chamber, seize the nearest file and get out before succumbing.

In these desperate and unusual activities we spent a good proportion of the next few days. In the end the offending papers were burned in the open in perforated petrol- drums, an old-fashioned but effective tech- nology. Some time later we drew the lesson from all this and arranged to carry no more paper than could be destroyed in our old- style shredder in half an hour. That we judged to be the longest we could hold out. The diplomatic bags were therefore deliv- ered, conscientiously read and as conscien- tiously destroyed. We experienced a great sense of relief and functioned quite as effi- ciently as before. At night Ray gathered the more vulnera- ble office effects into his bedroom for greater safety. I recall that then or shortly after he slept with a strange device, an incendiary deed-box, close to him. It was supposed to consume its contents in a cri- sis, at the same time emitting a high- pitched whistle. I had the same faith in it as in the incendiary powder.

Quietly, two days after the burning, our house servants returned. Service as before. I also found our Chinese office staff report- ing for duty, or, more precisely, hanging about in a guilty fashion. The great ques- tion, however, was the attitude of the Chi- nese government. We had had no word from them since the ultimatum of 20 August and for a week we existed in a kind of diplomatic limbo. The reason for this pause was presumably that the Chinese were preparing the strange episode of 29 August, what came to be known as the Bat- tle of Portland Place. On the morning of that day the British police posted outside the Chinese Mission in London were star- tled to find themselves facing an eruption of angry Chinese officials, armed with base- ball bats, axes and broom-handles. There were naturally injuries on both sides.

This curious piece of theatre was undoubtedly engineered by the Chinese so that they could claim to match us in terms of outrage and work themselves into the position of moral superiority from which they loved to operate. Late on Tuesday, 29 August, we were telephoned with orders to present ourselves at the Foreign Ministry at two the following morning. The timing of the interview indicated extreme displea- sure. By a refinement of cruelty it was later shifted to three o'clock.

Luo Guibo, the Vice Foreign Minister, delivered a 'most serious and strong protest'. He noted that the British Govern- ment had on 22 August taken illegal mea- sures against the Office of the Chinese Chargé d'Affaires and other Chinese estab- lishments in London. (This was a reference to the movement restrictions we had placed on the Chinese following the burning.) These must be immediately cancelled. Moreover, on the morning of 29 August the British Government had instigated ruffians to beat up Chinese personnel in London. On the afternoon of the same day police and ruffians had gone further. British policemen, clubs in hand, had flagrantly and brutally beaten up personnel of the Chinese Office. Three were severely wounded and more than ten others injured.

'1 can remember when modern art was new . . As a result, the Chinese government had decided that no personnel of the British Office were to leave China without permis- sion. All exit visas were cancelled. British activities were to be confined to their Office and residences and the road between. An application 48 hours in advance would be required for any attempt to move outside that area.

This was severe but not entirely surpris- ing. Our principal reaction was one of relief that we were recognised as diplomats and that the Office could continue to function. We had early breakfast in a relaxed mood. But we noticed that the compound was fill- ing up with soldiers, the usual prelude to trouble. Later that morning a group of Red Guards appeared at our temporary Office, the Whitney flat, and posted a notice call- ing on us to come down and face the mass- es. A large crowd was gathering just in front of the building. We telephoned the Protocol Department at the Foreign Min- istry and reminded them of our status and China's duty as host country. They told us we must face the masses.

A group of us then went out to meet the demonstrators. This was necessary; without it the violence could have become general.

It was an ugly demonstration, based of course on the alleged brutalities of Port- land Place. I remember some very large and very wild men literally hopping with rage in the front ranks. The army were there in strength but did not interfere. There were calls to bow our heads. When that did not happen one of the dervishes rushed forward and seized Donald Hop- son's hair, forcing his head down. The shouting and threats continued. At one point the officer in charge of the military detachment asked me quietly whether we could not perform a simple obeisance — a gesture would do. I explained it could not be done. Eventually, to our intense relief, the demonstrators marched away. We returned wearily to our Office.

Yet, after that low point, the situation gradually eased. We were of course marooned, but the sense of physical danger lessened. There was a curious incident the next day, when our servants demonstrated, together with Chinese office staff, outside my flat. They told me they had to leave to attend a meeting, but that lunch was ready on the stove. A few minutes later there were loud knocks on the door and I was confronted with raised fists and familiar faces contorted in ritual rage. I had a glimpse of the complexities of existence for the ordinary Chinese and the adjustments they constantly had to make between the demands of human reality and those of Maoist ideology.

That evening we had a small celebration for Donald Hopson's birthday and a show- ing of Les Belles de Nuit, borrowed from the French.

Experiences of China is to be published on 14 April by John Murray at £19.99.

Previous page

Previous page