'PEOPLE THINK I'M ABOUT TO DIE'

Sheridan Morley discusses the problems and

advantages of growing old in the theatre with Sir John Gielgud, who is 90 next month

A COUPLE of years ago, when I was just starting to write his biography, and long before the present controversy over whether or not a Shaftesbury Avenue the- atre should be named in his honour 1(to which the answer is clearly yes, and prefer- ably in the next couple of weeks), I asked Sir John Gielgud if he felt strongly about that kind of architectural immortality.

'I once rather liked the idea, but nowa- days I'm not so sure; they've taken to nam- ing them after such terrible people. In America, I hear, they have even started naming them after drama critics,' he said. And then, some vague recollection of my profession flashing through his memory, 'Only not you, of course.' The art of the great Gielgud brick is that the attempted retrieval always makes it somehow worse.

But, as we approach his 90th birthday on 14 April, there seems to be general amaze- ment that Sir John is not participating more eagerly in celebrations, has indeed rejected the ritual gala concert as 'too like a memorial'. This is to overlook first the instinct of the still working actor (never tell them how old you are, in case they think you might be uninsurable), and, sec- ond, the nature of the man himself. Giel- gud belongs, like his most immediate and apparent heirs, Guinness and Scofield and Jacobi (all of whom to some degree he started on their way), to that select group of player kings who believe it is enough just to act. Olivier and Finney and Burton and Branagh are or were all master show- men; Gielgud, partly because of a private life that was never exactly easy until he was well into his fifties, has always chosen to exist only on the far side of the footlights.

Not that I have ever known him unfriendly, or even ungregarious: indeed, one of the reasons he now turns up on minor film and television sets where many lesser classical actors might fear to tread (currently a tele-sequel to Gone With the Wind — 'tomorrow is another episode' as Scarlett almost said) is precisely for the company, that sense of belonging to a community of players.

'I never accept lengthy roles nowadays, because I'm always so afraid I'll die in the middle of shooting and cause such awful problems for everybody. But a day or two suits me very well, gets me out of Martin's way, and I have the chance to catch up on all the theatrical gossip with the other actors.'

Martin Hensler, the man with whom John has shared his life since the late 1950s and the key to his lge-life happi- ness, spends much of his time as one of the great gardeners of Buckinghamshire, at their splendidly baroque house (the wing of a once larger one) near Aylesbury, bought 20 years ago from the historian Arthur Bryant. 'I'm awfully bad at gar- dens, you know; I keep pulling up these weeds that turn out to be plants Martin has been nurturing for years, and so it's sometimes better to get back on a film set where I really belong.'

But the carefully fostered image of a faintly dotty old thespian, still hovering around the better-paid fringes of a world he once dominated as the greatest classical actor of the century bar none, is actually at odds with the truth about Gielgud. So far from easing himself into nonagenarian retirement, he is in fact celebrating his 90th as he most hoped: with a new King Lear for Radio 3. The actor who made his BBC radio debut exactly 70 years ago as Malcolm in Macbeth, the actor who first played Lear on stage over 60 years ago at the age of only 26, the actor who went on to play him at the Vic in 1940 for Granville-Barker (Tear is an oak, you are an ash: we shall have to see how it suits you') and at Stratford in 1950, and again there for Noguchi in 1955, is back in the role on BBC radio for the fourth time, in a production for which he is joined by the cast who can best do him honour: Judi Dench, Derek Jacobi, Kenneth Branagh, Robert Stephens, classicists all who grew up in the shadow of his greatness.

And what is so breathtaking about this new production is the sheer vivacity of Gielgud in the title role: none of the painful exhaustion of Olivier when, already ailing, he attempted it on television for the last time a decade ago, but instead a constantly alert, inventive, often unexpected reading, the result of a lifetime playing the role.

This, rather than any public party, is Gielgud's birthday present to himself and to us, and it could have been given by nobody else. A fascinating new collection of the programme notes he made as a young theatre-goer in the early 1920s, start- ing when he was still a day-boy at Westmin- ster School, shows that he was already there in the stalls, waiting, watching, learn- ing. 'Unspeakable' he writes of a 1924 Hamlet, but his praise for the ageing Eleanora Duse and the young Sybil Thorndike indicates how awake he already was to the myriad possibilities of stagecraft. Gielgud as actor and as director and as manager and as audience is quite simply the history of the British theatre in our century.

'I was always bleakly uninterested in power or politics of any kind, and I've never had the desire for any kind of public life that wasn't totally to do with acting. I saw how terribly ill and unhappy Larry became when he got caught up in the back- stage struggles of the National, and although I love the life of an acting compa- ny I grew terribly disenchanted with those great concrete bunkers they all work in nowadays. West End theatres may be crumbling, and the galleries may be uncomfortable, but at least they have a his- tory and a kind of spirit. I'm really much happier on a film set nowadays: in the the- atre they treat me as some dreadful old Dalai Lama come to give them notes.

'I left London and started a new life with Martin in the country when I realised, walking down Shaftesbury Avenue one day, that I could no longer recognise any of the names in lights, and I've been surprisingly happy ever since, happier than I ever thought I could be away from the West End. But I'm not at all sure I like this sud- den revival of interest in how old I am; it's probably because people think I'm about to die. Most of the scripts I get sent nowadays are about men at death's door, and the television people keep coming around say- ing they are filming a celebration of my life, when I know very well that what they really want is to have the obituary all ready in the can in case I pop off unexpectedly.'

Although he is far too well-mannered to make the point, it is Gielgud who has had the last stage laugh: all the other giants of his generation, from Olivier through Richardson to Redgrave, regarded him as the fragile one, 'virtually meaningless below the neck' in Ivor Brown's savage tribute to the most musical voice of its age, and yet there he is, the last survivor of the greatest classical team in the whole history of the British theatre. Whereas it took most of the 18th and 19th centuries to achieve Kean and Garrick and Macready and Kemble and Irving and John's great- aunt Ellen Terry, it was possible from the 1930s until well into the 1960s to see Giel- gud, Olivier, Redgrave and Richardson, not to mention Ashcroft and Evans, often in the same city and the same week and sometimes on the same stage.

If you can imagine, said Kenneth Tynan 40 years ago, that there is between good and great acting a fixed gulf which only those whose visas are in order can cross, then it is Olivier who goes over in one great animal leap. Redgrave plunges into the torrent and usually sinks within sight of the shore. But Gielgud? 'He goes over on a tightrope, parasol aloft.'

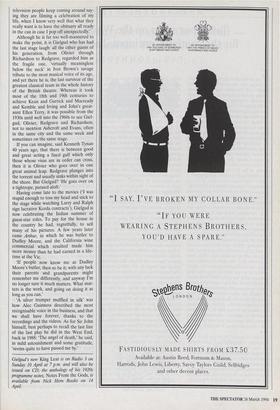

Having come late to the movies CI was stupid enough to toss my head and stick to the stage while watching Larry and Ralph sign lucrative Korda contracts'), Gielgud is now celebrating the Indian summer of guest-star roles. To pay for the house in the country he had, regretfully, to sell many of his pictures. A few years later came Arthur, in which he was butler to Dudley Moore, and the California wine commercial which resulted made him more money than he had earned in a life- time at the Vic.

'If people now know me as Dudley Moore's butler, then so be it; with any luck their parents and grandparents might remember me differently, and anyway I'm no longer sure it much matters. What mat- ters is the work, and going on doing it as long as you can.'

'A silver trumpet muffled in silk' was how Alec Guinness described the most recognisable voice in the business, and that we shall have forever, thanks to the recordings and the videos. As for Sir John himself, best perhaps to recall the last line of the last play he did in the West End, back in 1988: 'The angel of death,' he said, in mild astonishment and some gratitude, 'seems quite to have passed me by.'

Gielgud's new King Lear is on Radio 3 on Sunday 10 April at 7 p.m. and will also be issued on CD; the anthology of his 1920s programme notes, Notes From the Gods, is available from Nick Hem Books on 14

Previous page

Previous page