An Anglican, a patriot and a high Tory

David Wright

GOD BLESS KARL MARX! by C. H. Sisson

Carcanet, f4.95

Part of the Palgravian lie' — thus the late Patrick Kavanagh — 'was that poetry was a thing written by young men . . . Not having had access to Ezra Pound, who showed that the greatest poetry was writ- ten by men over 30, it took me many years to realise that poetry dealt with the full reality of experience.' As the work of Edward Thomas, whose first poem was written when he was 36, and that of C.H. Sisson, whose surrender to the Muse took place about the same age, demonstrates. All the same it is remarkable that a poet already in his seventies should produce a collection so full of vigour and fire as Sisson's latest offering, to my mind his best since the appearance of his second book of poems, Numbers, more than 20 years ago. One cannot say that Sisson has matured in the interval — again like Edward Thomas, as a poet he emerged fully armed, like Athena from the head of Zeus.

Sisson's intellect is as sharp as ever and hardly less savage. His is a poetry of thought, rather than of images or rhetoric or verbal prestidigitation; but one which acknowledges the irrational and subsumes that unknown quantity which gives wings to what would otherwise be verse. Not that verse, a rarer commodity than much that passes for poetry these days, is anything to look down one's nose at.

The angle of glance that provides the insights of these poems is not a fashionable one. Sisson is an Anglican, a patriot, and a high Tory of the kind that disappeared around 1649. What he has to say is not comfortable, least of all to the archbishops of Canterbury and York, whom he has apostrophised in verses which the addres- sees will no doubt castigate as scurrilous. Those for the Primate begin,

The Archbishop of Nothingness Blew up a bag of wind one day . . .

and those for the prelate of York have him reflecting

God, I am sure, won't touch my minster He only works in images, They're harmless, aren't they?

— a reference to the conflagration there, which puts one in mind of the uncomprom- ising prayer that circulated in Durham at the time of the induction of its new Bishop: `Almighty God, Whose arm was strong to strike the philistine in his unbelief, and hath in these last days visited Thy wrath upon the Minster at York . . . preserve, we beseech Thee, the fabric of this Holy Place from the wrath justly to be directed against those who doubt the miraculous strength of Thine arm.' Joking apart, the thought behind these comparatively trifling pas- quinades is deployed and elaborated in a passionate credo, his long lyric opening poem 'Vigil and Ode for St George's Day'. I can only quote its headlines, so to speak, and must omit its argument:

What is the cure for the disease Of consciousness? The cures are three. Sex, sleep and death — two temporary And only one that's sure to please . . . • . . When we have also drunk the cup Which will not pass, and when we leave The world we credit now for one Invisible under our sun And in which none of us can believe. So glory, laud, and honour all To the impossible, and most To Father, Son and Holy Ghost And let our own pretensions fall.

The austere landscape painted by Sisson's dour and logical realism is compactly ex- pressed in the preliminary verses that serve as a preface to this book:

Read me or not: I am nobody For myself as for others, and so true: If only it were also so with you Every accommodation would be easy.

But so it is not, for what we see Assumes as we look the mask of who, Doing convincingly what others do: So you become yourself without falsity. Or so it seems. But when delusion stirs It dreams of a mask, of his or hers, And so must you. Where is the truth in that? And you who read me read nothing, or worse, What you make out for yourself, some borrowed features.

Who is what you say but I answer, what?

The poems that follow this exacting intro- duction are nearly all meditations on identity, old age, and death:

The end that comes is not the end of what, The end of who perhaps, and perhaps not; The rattle and the flashing lights are over, Death is overt, but all the rest lies hidden. Think what you will, nothing will come of that, What you intend is of all things the least; As you spin on the lathe of circumstance You are shaped, it is all the shape you have.

Despite their themes and unillusioned viewpoint the poems are not petulant, as are so many of Philip Larkin's, due to a somewhat sentimental pessimism. It is sentiment, rather than sentimentality, which informs Sisson's `Taxila', a moving essay in nostalgia that recalls an incident when he was serving as a corporal in India:

Would I, the soldier of an alien army, Neither the first nor last to come that way, Purchase for rupees certain disused drach- mas Left by the army of an earlier day?

Sisson's mind, unblurred by cant, lends a marmoreal quality to many of his phrases, eg 'Evil with the face of charity' and to his epigrams: 'If things seem not to be as once they were/ Perhaps they are as once they seemed to be.'

To end with a note of criticism, the title poem 'God Bless Karl Marx!' doesn't really come off; irony, not overt satire, is Sisson's forte. But these new poems carry an exhilaration absent from the dry despair exhibited in some of his recent collections. It is a quality most clearly present in `Thoughts on the Churchyard and the Resting-places of the Dead' a superb Vii- lonesque rendering from the German of Andreas Gryphius: a poem which is in some sense a forerunner, by several cen- turies, of Valery's Cimetiere Marin.

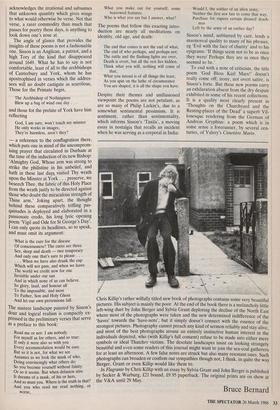

Chris Killip's rather wilfully titled new book of photographs contains some very beautiful pictures. His subject is mainly the poor. At the end of the book there is a melancholy little left-wing duet by John Berger and Sylvia Grant deploring the decline of the North East where most of the photographs were taken and the new determined indifference of the `haves' towards the 'have-nots', but it simply doesn't connect with the essence of the strongest pictures. Photography cannot preach any kind of sermon reliably and stay alive, and most of the best photographs arouse an entirely instinctive human interest in the individuals depicted, who (with Killip's full consent) refuse to be made into either mere symbols or ideal Thatcher victims. The desolate landscapes insist on looking strangely beautiful and even some readers of this journal might want to join the sea-coal gatherers for at least an afternoon. A few false notes are struck but also many resonant ones. Such photographs can broaden or confirm our sympathies though not, I think, in quite the way Berger, Grant or even Killip would like them to.

In Flagrante by Chris Killip with an essay by Sylvia Grant and John Berger is published by Secker & Warburg, £21 bound, £9.95 paperback. The original prints are on show at the V&A until 29 May.

Bruce Bernard

Previous page

Previous page