Who's afraid of Aer Lingus?

Christopher Hitchens

New York

By their action in staying away from the annual St Patrick's Day parade, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Governor Hugh Carey succeeded in reduc- ing the turnout by two people. The New York City police department marched at its usual strength. So did the National Guard. The massed phalanxes of the Holy Name Society, the Emerald Society and the An- cient Order of Hibernians were undepleted. Almost every county association from Tip- perary to Donegal had its complement of priests. Cardinal Terence Cooke, the moon- faced opportunist who represents God's vicar in the archdiocese of New York, did not take the salute from Michael Flannery and issued a convoluted statement to the ef- fect that all violence was to be deplored. But he announced later in the day that he had received Mr Flannery in a personal au- dience. 'I said we have a political process and that is the way to peace', intoned the cardinal, 'and as an Irish gentleman he said, 'I understand".'

Mr Flannery is used to dealing with the disapproval of clerics and other classes of quisling. Asked for his reaction to the Moynihan boycott, he was contemptuous. 'He's a nonentity, an Irishman for one day a year. He hasn't done a thing for us.' This is a bit rich — St Patrick's Day is nothing if not designed for the one-day-a-year Irishman. Or the one-day-a-year-honorary Irishman for that matter: I saw several brown bandsmen playing away for all they were worth. Policemen dye their moustaches green; nuns turn a blind eye to under-age drinking; bars discover all of a sudden that the landlord has an aunt in Limerick. Most of all, New York politicians with names like Mario Biaggi, Edward Koch and Mario Cuomo discover that the Irish question merits their urgent attention. (A good plan, if you run into these men or their supporters, is to ask them if they can name the six or the nine counties of Ulster.) Congressman Biaggi rather surpassed himself this year. At the traditional St

Patrick's Day breakfast, held at Charley O's Bar and Grill, he remarked thoughtful- ly: 'Flannery is the only grand marshal everybody will remember. At least it will focus attention on the human rights pro- blem in Northern Ireland.' Those two luminous sentences are best read in reverse order, where they make just as much sense. Of course, there are men and women who are Irish all year round. Every time I got(' P. J. Clark's bar on Third Avenue (a fine Irish resort where The Lost Weekend was filmed) I pass the pickets outside the neighbouring British consulate. They come here every day, and they move round in a rough circle, carrying placards which com- memorate Bobby Sands and vilify Margaret Thatcher. I can remember-feeling a pang of sorrow for them, one day last year, when in driving rain ' they were adding sodden Argentinian flags to their tricolours and starry ploughs. You can hear the occasional shout of 'Malvinas,' even to this day. Every now and then a passer-by will stop and press money into their hands with a hoarse injunction Clip the rebels' or 'Don't spend it on bandages').

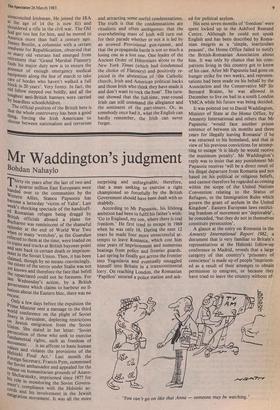

These men and women are magnificently indifferent to any kind of reproach. Does the Irish embassy condemn them? They don't give a damn. Does Aer Lingus withdraw its patronage from the parade? Who gives a freaking fig for Aer Lingo? Most non-Irish Americans don't realise that these are the descendants of the losing side in the Irish civil war. They live in America precisely because they regard the 'free state' as a parody of Irish nationalism. When they talk to liberals about the H-block detainees, they refer to them fetchingly as 'prisoners of conscience' or 'political prisoners'. But when they talk among themselves they call the lads 'prisoners of war'. In American domestic terms, most of these people are extremely reactionarY. They admire cops and detest blacks. TheY flourish the medals and the American Legion buttons, which show them to have been ultra-American. They have a soft spot for Senator Joe McCarthy (for the repose of whose soul a mass is read every year in St Patrick's Cathedral). The crowning absur- dity of all this came last November, when Michael Flannery and four of his confreres were put on trial for conspiracy to smuggle weapons. They did not plead not guilty — indeed they were anxious to sport their IRA credentials. They pleaded instead that the CIA had known of and sanctioned their plan. This convinced the judge and the jury (many of whose members were later spotted at an extremely convivial victory celebra- tion). Flannery is just the Model example of the unreconciled Irishman. He joined the IRA at the age of 14 (he is now 81) and Shouldered a rifle in the civil war. The Old Sod got too hot for him, and he moved to America more than half a century ago. Jimmy Breslin, a columnist with a certain tendresse for Republicanism, observed that SO .many old veterans had emerged from retirement that 'Grand Marshal Flannery finds his major duty now is to ensure the Presence of enough. emergency medical equiPment along the line of march to take care of hordes who haven't walked a full block in 20 years'. Very funny. In fact, the old fellow stepped out boldly, and all the t°ughest anti-British banners were carried best

beardless schoolchildren.

The official position of the British here is that the whole controversy has been a good thing, forcing the Irish Americans to choose between nationalism and terrorism and attracting some useful condemnations. The truth is that the condemnations are ritualistic and often ambiguous: that the overwhelming mass of Irish will turn out for their parade whether or not it is led by an avowed Provisional gun-runner, and that the propaganda battle is not so much a losing one as a lost one. One leader of the Ancient Order of Hibernians wrote to the New York Times (which had condemned the choice of Flannery) and positively re- joiced in the abstention of 'the Catholic church, Irish and American political hacks and those Irish who think they have made it and don't want to rock the boat'. The turn- out showed that the full-time, year-round Irish can still command the allegiance and the sentiment of the part-timers. Or, as somebody once had it, what the English can hardly remember, the Irish can never forget.

Previous page

Previous page