Giorgione's artistic poetry

Mark Glazebrook on a magnificent exhibition of work by 'Big George' in Vienna

Giorgione! A name to conjure with. Other names such as Vasari, Byron and Walter Pater have conjured with the Zorzi, Zorzo or Zorzon of contemporary documents, the exceptionally talented painter who died in his early thirties in 1510, the legendary Big George, the gifted musician and fabulous lover who came to Venice from Castelfranco, a large fortified village situated in a great broken plain at some distance from the Venetian Alps. His copses, glades, brooks and hills must surely have inspired the Giorgionesqe ideal of pastoral scenery. Now, more than 20 different living scholars are battling it out with each other in 14 essays and some 25 individual catalogue entries in the publication which goes with Myth and Enigma, the current Giorgione exhibition in Vienna, a show which began in Venice.

The whole experience is stimulating, tantalising and not unlikely to induce obsession. There are more Giorgione experts involved in this show than pictures worldwide that are agreed to be autograph works. As the curator Sylvia Ferino-Pagden puts it: 'Today Giorgione is regarded as a unique phenomenon in the history of art: almost no other Western painter has left so few secure works and enjoyed such fame for almost 500 years.'

As with many great artists, composers and writers, Giorgione's work, or in his case each 'secure' example of it, is likely to appeal on many different levels. Whether you are interested in the inexplicable power of colour, Greek and Roman myths, smoky Leonardoesque transitions, or sfumato, the history of dress, the birth of landscape painting as an art form in its own right, the Holy Bible and scenes from it, the seem ingly miraculous improvement of portraiture c.1500, Muslim and Jewish culture, beautiful effects obtained by subtly combining oil and tempera, Renaissance literary studies, astrology, thunderstorms, sexual electricity or just looking at marvellous paintings, then Giorgione is for you.

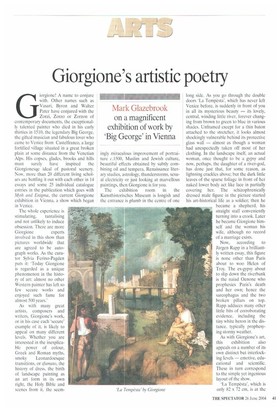

The exhibition room in the Kunsthistorisches Museum is longish and the entrance is plumb in the centre of one long side. As you go through the double doors 'La Tempesta', which has never left Venice before, is suddenly in front of you in all its mysterious beauty — its lovely, central. winding little river, forever changing from brown to green to blue in various shades. Unframed except for a thin baton attached to the stretcher, it looks almost shockingly vulnerable behind its protective glass wall — almost as though a woman had unexpectedly taken off most of her clothing. In the landscape itself, an actual woman, once thought to be a gypsy and now, perhaps, the daughter of a river-god, has done just that, for some reason, as lightning crackles above; but the dark little leaves of the sparse foliage in front of her naked lower body act like lace in partially covering her. The schizophrenically dressed male figure in the picture started his art-historical life as a soldier; then he became a shepherd, his straight staff conveniently turning into a crook. Later he became Giorgione himself and the woman his wife, although no record of a marriage exists.

Now, according to Jurgen Rapp in a brilliantly written essay, this figure is none other than Paris about to woo Helen of Troy. The ex-gypsy about to slip down the riverbank is the naiad Oenone who prophesies Paris's death and her own; hence the sarcophagus and the two broken pillars on top. Rapp adduces many other little bits of corroborating evidence, including the tiny white heron in the distance, typically prophesying stormy weather.

As with Giorgione's art, this exhibition also appeals on a number of its own distinct but interlocking levels — emotive, educational and scientific. These in turn correspond to the simple yet ingenious layout of the show.

'La Tempesta', which is only 82 x 72 cm, is at the centre of an open inner rectangle formed by a series of free-standing screens or stands with gaps between them. On the extreme left of this inner rectangle is Vienna's own larger but equally enigmatic painting 'Three Philosophers', with its dark brown cave dominating the left half of the space. By the 1920s it had become, on slender evidence, `Evander showing Aeneas the Site of Troy'. Then it was 'Three Magi', then a Jew, a Muslim and a Christian, followed by the more specific Moses, Mohammed and Jesus. Now, according to Augusto Gentile, the former Jesus figure is the Antichrist. Oh dear!

Opposite the 'Three Philosophers', on the far right, is the smaller 'La Vecchia', the portrait of an old woman which looks forward to Velazquez in its sober, authoritative realism. To the left of 'La Vecchia' is a horrible little Direr of a wrinkle-breasted old hag. The excuse for its inclusion is that it may have given Giorgione the idea of portraying an old woman. More fruitfully it provides an opportunity to discuss the whole relationship between Northern and Southern painters in the catalogue, which is published jointly with the Soprintendenza Speciale per il Polo Museale Veneziano.

Mercifully, however, most of the other pictures in the inner rectangle arc autograph works from different periods, about a dozen in all, it would seem, plus some instructive doubtfuls and one copy of a self-portrait — or is it a fake?

Behind the inner rectangle there is some superb back-up material, including four Titians, a Catena and a highly relevant picture of a picture gallery by David Teniers the Younger. What gives the show its unusual fascination, however, are the Xrays. Behind each Giorgione is an infra-red image showing first thoughts and pentimenti. The standing man in 'La Tempesta' was once a crouching woman. 'Oenone's sister,' says Rapp. The face of the putative Antichrist in 'Three Philosophers' has a putatively wicked expression. A possible point for Gentile except that the central figure was once a black man which helps the 'Three Magi' school of thought.

I was disappointed not to see Dresden's matchless 'Sleeping Venus', but in the autumn of 2006 Vienna is mounting Bellini, Giorgione and Titian: The Renaissance of Venetian painting 1500-1530. Perhaps it will he lent then.

The current show remains a must and should help scholars to prepare for the forthcoming triple-bill. Some argue that Giorgione was simply aiming to produce a visual equivalent of poetry with all the licence that entailed. This view rather spoils the fun of the scholars but time may indeed prove that an essential part of Giorgione's charm is that, in his case, beauty will always be easier to come by than precise truth.

Myth and Enigma is at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, until 11 July.

Previous page

Previous page