Architecture

The broken line

Alan Powers on modern neglect of architectural composition How does architecture happen? What in one building provides a greater aesthetic

stimulus than another? How easy is it to miss the point altogether? It must be one of the jobs of the architectural critic to dis- tinguish quality, although 'value judgment' is a term evoked with horror in many sec- tions of the academic world.

Before the advent of Modernism in architecture (in England, a gradual process from 1930 to 1950), composition was one of the criteria of critical judgment. This was not a judgment of style, or of exact relation to function, or of economic use of materi- als. It was nearly pure aesthetics, anchored to reality through experience and tradition.

Composition has not been a subject of study in architectural schools for many years. Like all the aesthetic aspects of architecture, it was always difficult to teach. Modernism offered the great eva- sion: the plan is the generator, form follows function — let the building assume its own life regardless of convention and prece- dent. Yet composition in architecture, analogous to music at the opposite end of the hierarchy from useful to pure arts, can- not be ignored.

There are, of course, fine buildings from the early days of Modernism to prove that conventions can be overthrown and new forms created. The powerful inventions of Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto have earned them the title of `form-givers' — with a sinister implication that their forms will be enough to keep architects going indefinitely.

This fiction has worn thin. Now there is a gap between those who compose in the `traditional' Modern Movement manner, seeking formal inspiration from the build- ing's programme, usually, like Colin St John Wilson and Denys Lasdun, from the older generation, and those younger Mod- ernists who have virtually abdicated from the responsibility to compose a building.

The creation of flexible space without emphasis or direction, or the design extrud- ed in section as if squeezed out of a tooth- paste tube are two ways of avoiding composition, but the nature of the architec- tural object is harder to change. The empti- ness nags in the mind's eye.

To place too much emphasis on compo- sition in architecture may lead to an archi- tecture of façades, unrelated to function and unable to draw its vitality from the life contained within the building, but to ignore the matter altogether leaves a building equally impoverished, as most of the cre- ations of High Tech architecture will surely appear when the initial gloss has worn off.

To attempt composition and to do it clumsily is equally unsatisfactory. That the line of descent has been broken which con- nected architects of the 1920s to their pre- decessors, and that a climate of emulation and support is lacking, is sadly apparent in contemporary Classical work. I do not know what the Beaux Arts professors of 19th-century Paris, the guardians of the compositional tradition, would have made of Terry Farrell's Vauxhall Cross building — with its piling up of symmetrical features a piece of style pompier rather than a grand public building for the river bank of a capi- tal city. How would they have reacted to Brentwood Cathedral by Quinlan Terry, which in a facade of 11 bays has five differ- ent points of emphasis, the two main sec- ondary emphases being unrelated to the plan? As the critics Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre have written of Terry's Richmond Riverside, 'It is almost as if he could read correctly the individual notes and chords of Mozart without being able to produce the phrases, to perceive the the- matic structures'.

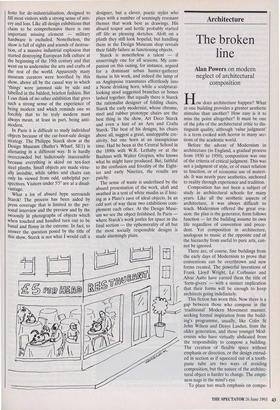

The general failure to acknowledge the importance of composition in architecture has been apparent in the recent conserva- tion battle over a house in Old Church Street, Chelsea, designed in 1935 by Eric Mendelsohn, the German émigré Mod- ernist, with his partner Serge Chermayeff. When Sir Norman Foster's plans to extend and alter the house were given permission last autumn, an outcry from lovers of Mendelsohn's scarce work arose, for he was an architect for whom composition was the key to design, an aesthete first and a functionalist second.

Mendelsohn, like the other modern architects who came to England from Europe in the 1930s, brought with him a richer architectural culture. He combined a desire for speed and modernity with a mys- tical sense of tranquillity. Music was an essential aspect of his life and his design technique. In Mendelsohn's buildings, composition became more dynamic and three-dimensional than in the classical tra- dition. The dynamism is recognised in his famous first work, the Einstein Tower in Potsdam, but you could no more build that in Chelsea in 1935 than you could today. Mendelsohn smoothed and compacted the angular forms of his early work until, by his English period, the force was encapsulated in deceptively simple forms. To enable him to do this, he listened again and again to certain pieces of music, above all Bach, and finally satisfied the client's desire for a squash court within the volume of the house, celebrating this modern amenity internally by giving it the gravitas of an Egyptian tomb. The assistant's job in the office was to keep winding the gramo- phone.

In the proposals, two divergent streams of modern architecture confronted each other in mutual incomprehension. Sir Nor- man Foster has written of his proposals: `It's all really rather a non-event'. The addi- tion of a conservatory and the creation of some new windows may sound insignifi- 64 Old Church Street, Chelsea, Eric Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff, 1935-36 cant, but the work now going forward, maddeningly tasteful and restrained, is as superfluous and frivolous as wrong notes scored into a Brandenburg concerto.

Previous page

Previous page