'A CERTAIN AMOUNT OF VINDICTIVENESS'

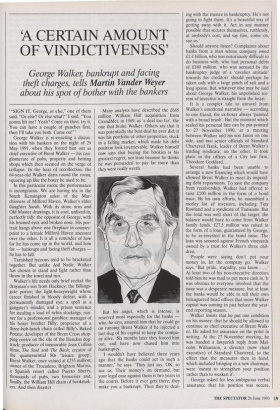

George Walker, bankrupt and facing

theft charges, tells Martin Vander Weyer

about his spot of bother with the bankers

"SIGN IT, George, or else," one of them said. "Or else? Or else what?" I said. "You gonna hit me? Yeah? Come on then, try it. You can have a couple of punches first, then I'll take you both. Come on!"' George Walker is re-enacting a discus- sion with his bankers on the night of 29 May 1991, when they forced him out as chief executive of Brent Walker — his con- glomerate of pubs, property and betting shops which then seemed on the verge of collapse. In the heat of recollection, the 64-year-old Walker darts round the room, squaring up like the boxer he used to be.

In this particular room, the performance is incongruous. We are having tea in the South Kensington salon of the Mar- chioness of Milford Haven, Walker's elder daughter Sarah. With its stone urns and Old Master drawings, it is cool, unlived-in, perfectly tidy: the opposite of George, with his bruised eyes and broken nose. His por- trait hangs above one fireplace in counter- point to a female Milford Haven ancestor over the other. It is all a reminder of how far he has come up in the world, and how far — bankrupt and facing theft charges he has to fall.

Tarnished tycoons tend to be bracketed together. But unlike Asil Nadir, Walker has chosen to stand and fight rather than throw in the towel and run.

Walker's life needs only brief recital: the drayman's son from Hackney; the Billings- gate porter; the light-heavyweight whose career finished in bloody defeat, with a permanently damaged eye; a spell as a gangster's minder, and a prison sentence for stealing a load of nylon stockings; run- ner for a professional gambler; manager of his boxer brother Billy; proprietor of a three-bob-lunch chain called Billy's Baked Potato; developer of the Brent Cross shop- ping centre on the site of the Hendon dog- track; producer of memorable Joan Collins films, The Stud and The Bitch; creator of the quintessential 80s 'leisure group', Brent Walker, once valued at £255 million; owner of the Trocadero, Brighton Marina, a Spanish resort called Puerto Sherry, thousands of pubs, two breweries and, finally, the William Hill chain of bookmak- ers. And then disaster.

Many analysts have described the £685 million William Hill acquisition from GrandMet, in 1989, as 'a deal too far', the one that broke Walker. Others say that it was potentially the best deal he ever did; it was his portfolio of other properties, stuck in a falling market, which made his debt position look irretrievable. Walker himself now says that buying the bookies is his greatest regret, not least because he thinks he was persuaded to pay far more than they were really worth.

But his anger, which is intense, is reserved most especially for the banks who, he says, assured him that he could go on running Brent Walker if he injected a last slug of his capital to keep the compa- ny alive. Six months later they forced him out, and have now chased him into bankruptcy.

`I wouldn't have believed three years ago that the banks could act in such a manner,' he says. 'They just say, OK, so sue us. Their money's on demand, but your legal case against them is two years in the courts. Before it ever gets there, they make you a bankrupt. Then they're deal-

ing with the trustee in bankruptcy. He's not going to fight them. It's a beautiful way of getting away with it. Act in any manner possible that secures themselves, ruthlessly, at anybody's cost, and say fine, come on, sue us.'

Should anyone listen? Complaints about banks from a man whose company owed £1.4 billion, who was notoriously difficult to do business with, who had personal debts of £180 million, who was accused by the bankruptcy judge of a 'cavalier attitude' towards his creditors should perhaps be taken only with a large pinch of salt and a long spoon. But, whatever else may be said about George Walker, his unpolished tor- rent of invective is straight from the heart.

It is a complex tale to unravel from Walker's emotional narrative — according to one friend, the ex-boxer always 'painted with a broad brush'. But the moment which sealed his personal fate can be pin-pointed to 27 November 1990, at a meeting between Walker and his son Jason on one side, and two senior officials of Standard Chartered Bank, leader of Brent Walker's lending syndicate, on the other. It took place in the offices of a City law firm, Theodore Goddard.

Several banks had been unable to arrange a new financing which would have allowed Brent Walker to meet its impend- ing debt repayments. To save the company from receivership, Walker had offered to raise £100 million in the form of a bond issue. By his own efforts, he assembled a motley list of investors, including Tiny Rowland and a syndicate of Tunisians. But the total was well short of the target; the balance would have to come from Walker family funds. £27.5 million was raised in the form of a loan, guaranteed by George, to be re-invested in the bond issue. The loan was secured against French vineyards owned by a trust for Walker's three chil- dren.

`People were saying don't put your money in, let the company go,' Walker says. 'But pride, stupidity, you know . • ' At least two of his non-executive directors told him he was mad to put more cash in. It was obvious to everyone involved that the issue was a desperate measure, but at least the banks would be able to tell their own beleaguered head offices that more Walker capital was coming in just before the year- end reporting season.

Walker insists that he put one condition on his money: that he should be allowed to continue as chief executive of Brent Walk- er. He asked for assurance on the point in writing. At the 27 November meeting, he was handed a lawyerish reply from Mal- colm Williamson, a director (now chief executive) of Standard Chartered, to the effect that the measures then in hand, which included bringing in a new chairman, were 'meant to strengthen your position rather than to weaken it'.

George asked for less ambiguous verbal assurance that his position was secure, from another Standard Chartered official, Erick Naslund. A Brent Walker non-exec- utive was called in to witness the discus- sion. He subsequently swore an affidavit that 'it was quite clear to me that that assurance was given, both from the terms of the letter and Naslund's response, although I cannot now recall his precise words'. The bond issue was completed.

But Brent Walker's financial condition was still deteriorating. Within two months, Walker became convinced that the banks were determined to oust him, chiefly because he would not agree to sell off assets at knock-down prices. 'There was never a thought of keeping me,' he says.

`He was livid,' according to one director, `and very aggressive with them.' George was impossible,' says an adviser to the company. 'He just pressed on as if he owned it 100 per cent.' You never knew where you were with him,' one banker says. 'I liked old George,' says another, one of the toughest men on the case, tut he was always a buyer; he never wanted to sell anything.'

One of the things Walker says the bankers wanted him to sell at a substantial loss was William Hill. He refused. The other bone of contention was his negotia- tion with Tiny Rowland, who considered buying part or all of Brent Walker but, according to George, would deal only with him and not with the company's new chair- man, Lord Kindersley, an old-school City figure who was himself eased out by the banks after a brief tenure. Kindersley had not been a party to the 27 November meeting, and says it is 'unbelievable' that an open-ended commitment could have been given to Walker; there might, howev- er, have been 'soothing noises'.

`At that stage,' Kindersley says, 'the banks were quite long-suffering with George. But he kept changing the parame- ters and I thought he was undermining confidence in any possible restructuring. I was primarily responsible for the move to get him out.'

That move came on the night of 29 May 1991. A Brent Walker board meeting began at 11 p.m. The bankers, led by Williamson, were in attendance to present the board with a capital restructuring pro- posal. It included a `ratcheting' incentive for directors — a share option deal which would increase the directors' rewards according to the improvement in Brent Walker's profits and the reduction of its debt. But the banks would only 'commend' the plan, and continue to support the com- pany, if George and one other director departed. If they refused to go, the banks would call in receivers at the opening of business next morning.

The banks' new hostility to Walker, after months of negotiation, had been signalled to the board only in the previous 48 hours. To some of those present, the bankers' conduct was outrageous. The company's lawyers were present, but the bankers would not let the board adjourn to hear counsel's opinions, or to compose their own thoughts on the unprecedented choice which faced them; nor could George consult his own solicitor. Several directors felt that they were being forced to a decision. With the 'ratchet' deal on offer if the company survived the night, it was, in Walker's words, 'carrot and stick'.

There were vicious side-arguments, including (by Walker's account) the alter- cation between George and the bankers with whom we began. At another moment, George declared (according to another director) that if he was forced out, the banks would have to release him from the vineyard loan connected to the bond issue; to be told that, on the contrary, the banks would pursue him for the last penny. 'I'll chase you up hill and down dale, George,' is his own recollection of the threat. 'I'll have you a bankrupt.'

Proceedings came close to chaos, recriminations flying around the board table. Finally, after 4 a.m., George was sacked as chief executive of Brent Walker — by six votes to five, with three absten- tions — and escorted from the building by the company secretary.

`No doubt about it,' Walker says, 'the banks got away with murder and it's not basically right. Ifs basically wrong, but they don't care. It's like, you wouldn't do as you were told so now we're going to get you, you bastard. That's a fundamental wrong.'

Could George really have hoped to go on? Given Brent Walker's day-to-day dependence on bank support and the state of George's relations with the bankers, apparently not — but the banks had given him the impression six months earlier that he could. He was, after all, Brent Walker's founder, driving force and major share- holder; the bond issue was the clearest pos- sible evidence of his commitment to the survival of the company. And, rightly or wrongly, he was the only person who understood the business from top to bot- tom.

At that stage, there had been no sugges- tion of any possible malfeasance by Walk- er. And, according to one non-executive, George was by no means as difficult to handle as the banks suggested: he certainly listened to his board. Another says categor- ically, 'George . . . was the best man to run the company.'

The irony is that Brent Walker, now run by the former London Transport chief, Sir Keith Bright, has survived by a strategy very close to George's own, over which he disagreed so violently with his bankers at the time. Neither William Hill nor any other major asset has been sold.

But George himself has been ruined. He sought to keep his head above water by means of an 'individual voluntary arrange- ment', accepted by a majority of his credi- tors, which would have given them a few pence in the pound as and when he had any disposable income. But five banks swiftly attacked the voluntary deal and pur- sued him into bankruptcy.

Convinced that the banks were going to have the voluntary arrangement over- turned, he did little to help his case. He made no payments out of income — although he had been working on behalf of his wife's company, selling cigarettes to Russia — and was told by the judge that he was not 'playing fair'. He had also told his wife not to make payments required of her to cover the legal costs of two court cases which, if successful, might eventually have realised large sums for his creditors.

The two cases were his wrongful dis- missal claim against Brent Walker — to which the conduct of the 29 May board meeting is crucial — and his claim that the £27.5 million vineyard loan should be set aside because the banks broke the assur- ance given at the 27 November meeting, which was a condition of his signature. Walker believes that the trustee in bankruptcy will now quietly settle both cases, rather than pursuing them through the courts.

Lord Kindersley is one observer who sus; pects 'a certain amount of vindictiveness' on the part of the banks in the dispute over the vineyard loan. The bankers involved deny the accusation, or that they favoured bankruptcy because it effectively kills off George's counter-claims in the courts. `it was purely a commercial decision,' one of them says. 'He owes the banks a hell of a lot of money.' In particular, he argues, bankruptcy enables the trustee, under Sec- tion 366 of the Insolvency Act, to interview the rest of the Walker family under oath as to the whereabouts of any remaining assets.

There is no doubt, with hindsight, that, like a lot of people in the 80s, George Walker was a fool to borrow so much money and the banks were fools to lend it to him. As a devoted family man, he was reckless to stake his children's trust fund against an uncertain assurance, and some would say that the banks were reckless to let him. In his own words, George was 'a bit rough with people', and one of his col- leagues says that 'he tended to think that the end justified the means'. His bankers, it seems, thought the same way. Their means were unusually brutal, and there will be nothing for them to be proud of in the Walker story's end.

Previous page

Previous page