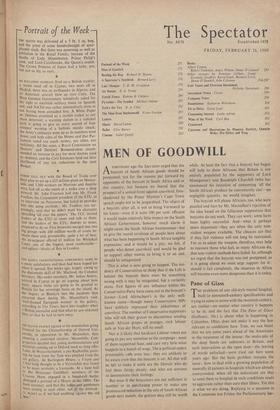

Pane of Glass

rr HE problems of any old-style mental hospital, i built to nineteenth-century specifications and trying to come to terms with the twentieth century, are similar—no matter what country it happens to be in; and the fact that The Pane of Glass (Gollancz, 30s.) is about what is happening in Columbus, Ohio, does not make it any the less relevant to conditions here. True, we can boast that we are some years ahead of the Americans in the treatment of the insane; the snake-pits of the deep South are unknown in Britain, and such innovations as the open door—the leaving of wards unlocked—were tried out here some years ago. But the basic problem remains the same: how to deal with a growing population of mentally ill patients in hospitals which are already overcrowded, when all the indications are that to send them to hospital in such conditions tends to aggravate rather than cure their illness. Yet this is what we are doing. Replying to a question in the Commons last Friday the Parliamentary Sec- retary to the Minister of Health revealed that almost half-48 per cent.—of the hospital patients in this country are in mental hospitals; and the most urgent medical problem of our time is how to get them out.

John Bartlow Martin's study of Columbus State Hospital is particularly valuable not because it suggests any easy solution but because it reveals, sympathetically and without prejudices, why there is no easy solution. The tranquillising drugs from which so much was hoped are indeed a help; but all they can do is to bring a patient within reach of treatment—they cannot as a rule ctire him, any more than hydrotherapy did. Electric shock treatment, too, has its uses, but its serious limita- tions are now recognised; and leucotomy—though Mr. Martin is too polite to say so in so many words—has been exposed as a particularly ugly blind alley. For the great majority of patients there is no known treatment except painstaking, sympathetic care and understanding; and this, of course, is impossible to provide so long as the medical profession, despising and resenting psy- chiatry, allows it only a tiny share of students' time, starves it of money for research, and deprives the mental hospitals of a fair share of National Health Service funds.

So there are still mental hospitals that look like gaols—and, as far as their inmates are concerned, are gaols. Leucotomy is still performed; electric shock and drugs are given, in some hospitals, less as a treatment than as a punishment. The need for more and better out-patient clinics, social workers and nurses was known even before the success of the recent Worthing experiment; but the funds are not available. The result is that treatment is often postponed until the patient has passed the point of no return.

Previous page

Previous page