An interview with Iris Murdoch

Simon Blow

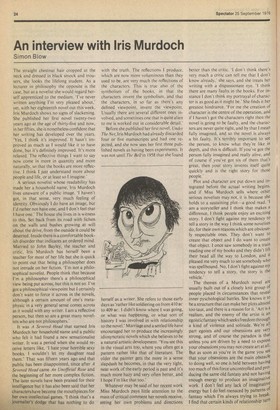

The straight chestnut hair cropped at the neck and dressed in black smock and trousers, she looks the lifelong student. As a lecturer in philosophy the opposite is the case, but as a novelist she would regard herself apprenticed to the medium. 'I've never written anything I'm very pleased about,' yet, with her eighteenth novel out this week, Iris Murdoch shows no signs of slackening. She published her first novel twenty-two years ago at the age of thirty-five and now, in her fifties, she is nonetheless confident that her writing has developed over the years. 'Yes, I think it's improved. It hasn't improved as much as I would like it to have done, but it's definitely improved. It's more relaxed. The reflective things I want to say now come in more in quantity and more naturally, so that the books are more reflective. I think [just understand more about people and life, or at least so I imagine.'

A serious novelist whose readability has made her a household name, Iris Murdoch lives unaware of a public image. 'I haven't got, in that sense, very much feeling of identity. Obviously I do have an image, but I'd rather not have one, and I don't feel that I have one.' The house she lives in is witness to this. Set back from its road with lichen on the walls and bushes growing at will about the drive, from the outside it could be deserted. Inside there is a comfortable bookish disorder that indicates an ordered mind. Married to John Bayley, the teacher and critic, Iris Murdoch has herself been a teacher for most of her life but she is quick to point out that being a philosopher does not intrude on her fiction. 'I'm not a philosophical novelist. People think that because I'm a philosopher there's a philosophical view being put across, but this is not so. I've got a philosophical viewpoint but I certainly don't want to force it across in the novels, although a certain amount of one's meta physic in a very general sense comes across as it would with any writer. I am a reflective person, but then so are a great many novelists who are not philosophers.'

It was A Severed Head that earned Iris Murdoch her household name and a public who felt it had found a new sensationalist writer. It was a period when she would receive letters like, 'I hate your horrible sexy books. I wouldn't let my daughter read them.' That was fifteen years ago and that public has been disappointed, since after A Severed Head came An Unofficial Rose and the beginning of her more complex fiction. The later novels have been praised for their intelligence but it has also been said that her characters have become the mouthpieces for her own intellectual games. 'I think that's a journalist's dodge that has nothing to do with the truth. The reflections I produce, which are now more voluminous than they used to be, are very much the reflections of the characters. This is true also of the symbolism of the books, in that the characters invent the symbolism, and that the characters, in so far as there's any defined viewpoint, invent the viewpoint. Usually there are several different ones involved, and sometimes one that is quite alien to me is worked out in considerable detail.'

Before she published her first novel, Under The Net, Iris Murdoch had already discarded four or five manuscripts and had one rejected, and she now sees her first three published novels as having been experiments. It was not until The Bell in 1958 that she found

herself as a writer. She refers to those early days as 'rather like soldiering on from 410 Etc to 409 ec. I didn't know where I was going, or what was happening, or what sort of history I was involved in with relationship to the novel.' Marriage and a settled life have encouraged her to produce the increasingly idiosyncratic novels which she believes to be a natural artistic development. 'You see this in the visual arts too, where you often get a pattern rather like that of literature. The older the painter gets the more in a sense slapdash he becomes, in that the very tight, neat work of the early period is past and it's much more hazy and very often better, and I hope I'm like that too.'

Whatever may be said of her recent work Miss Murdoch pays little attention to the mass of critical comment her novels receive, seeing her own problems and directions better than the critic. 'I don't think there's very much a critic can tell me that I don't

know already,' she says, and she treats her

writing with a dispassionate eye. 'I think there are many faults in the books. For in stance I don't think my portrayal of charac ter is as good as it might be.' She finds it her greatest hindrance. 'For me the creation of character is the centre of the operation, and if I haven't got the characters right then the novel is going to be faulty, and the characters are never quite right, and by that I mean fully imagined, and so the novel is always a bit faulty. It's terribly important to see the person, to know what they're like in

depth, and this is difficult. If you've got the

person fully imagined and really alive, and of course if you've got six of them that's great, then your story invents itself quite quickly and is the right story for those people.'

Plot and character are put down and integrated before the actual writing begins.

and if Miss Murdoch sells where other serious novelists may not, it is because she holds to a sustaining plot --a good read. 'I am a storyteller and I think that makes a difference, I think people enjoy an exciting story. I don't fight against my tendency to tell a story in the way I think some novelists

do, for their own reasons which are obviously respectable ones. They don't want to

create that object and I do want to create that object. I once saw somebody in a train reading one of my books and they didn't lift their head all the way to London, and it pleased me very much to see somebody who was spellbound. No, I don't tight against mY tendency to tell a story, the story is the vehicle.'

The themes of a Murdoch novel are usually built out of a closely knit group of people placed in circumstances that reveal inner pyschological battles. She knows it to be a structure that can make her plots almost too taut, and there is a reason for it. 'Art is a realism, and the enemy of the artist is an egoistic fantasy which seeks freedom through a kind of violence and solitude. We're all part egoists and our obsessions are very strong, and of course the paradox is that unless you are driven by a need to express your obsessions you may not create art at all But as soon as you're in the game you see that your obsessions are the main obstacle to doing well, so one is held between having too much of this force uncontrolled and pro

ducing the same old fantasy and not having enough energy to produce an imaginative work. I don't feel any lack of imaginative energy but I do feel menaced by patterns of fantasy which I'm always trying to break. I find that certain kinds of relationship turn tin again. For instance being an only child I find that I have sibling obsessions and I'm very interested in relations between brothers and brothers, and brothers and sisters and so on, which I've never had. So there's this empty space into which one projects this energy, and doubtless connectea with childhood situations one wanted.'

In her new novel Henry and Cato the sibling obsession is more mildly stated than it is in previous books, but there is a preoccupation with religion. 'I'm much more interested in religion and I think I know much more about it than I did when I started. People's attitude to religion is an important aspect of life. How they're nonreligious if they're non-religious, and how they've been brought up, all this interests me. I feel very worried about the disappearance of religion from people's lives. I am not a believer myself in any personal God and I used to think it meant that I wasn't religious any more, that religion was something childish or gone, but now I feel at some new Understanding of it—a Buddhist understanding perhaps. This adds a dimension to reflections about people's minds and how they react in trouble which is different from What I was doing in the beginning.'

Although there is more reflection in her work now, the plots are no less chilling or dramatic than in the days of A Severed Head and the need to love and to be loved still governs her outlook. 'Yes, this is absolutely fundamental to everything, and this is where I'm a Platonist or rather a Freudian in a non-dogmatic sense. The notion that there IS a deep Eros force that drives one to either fulfilment or disaster, love, hate or possession, iscentral, but it's the detail that matters.' But do people necessarily want fulfilment ? 'Yes, I think people do seek the highest in their own way, but their highest may be a perverted one or a lost one.' But in spite of her treatment of the emotionally maimed Miss Murdoch is not a pessimist. 'Of course there can be happy marriages—I've got one myself—and people can have very steady, relaxed trusting relationships with each Other, and there are such persons in my books, but one tends to remember the People who are demonic or come to grief.'

Alongside her fiction Iris Murdoch has continued to work at philosophy and, although she no longer teaches, her next book Will be an extended essay on Plato. She finds Philosophy far more difficult than fiction, and finds it impossible to write them simultaneously. 'Philosophy is a counter-natural activity that goes against the bent of the human mind whereas art goes with the bent Of the human mind. There's a myth in Plato about the world being pushed one way by God for a certain period, then God lets go and it rolls back in a natural way. [feel that Philosophy is pushing the cosmos in a directlon which is unnatural to it, and then when You let go you're back in art and you heave '`et sigh of relief and you're flowing with the urrent and your canoe is careering down the river..

Her publication on Plato—an exposition of his Eros theme, and one that is understandably sympathetic to her—will be her third book of philosophy, but it is unlikely to keep her away from fiction for long. One novel finished, she is ready to begin the next within an hour and tackle the blocks of invention with an accustomed stoicism. 'I find inventing a novel very difficult. I can write it quite easily once I've invented it. There are times when absolutely nothing comes and it all looks stupid and weak, but then there are spurts forward as you go on battering at the problem.' But that Henry and Cato is her eighth novel over nine years is proof of her statement that, for her, fiction is a pleasurable and not an exhausting experience.

With such a consecutive output at such an achieved level, does she feel any overall pattern emerging? 'That's very hard to say, and if there is I'd rather not know about it when I start a book. I feel with every novel that a completely new start is taking place, as if nothing had been done or thought before. But I suppose looking back I can see a sort of development. I think my ideas on love and freedom have changed very greatly over this period. Like the conflict between an idea of freedom which is an egoistic jerking about, and an idea of freedom which is an understanding of oneself and one's situation and an acceptance of other people and their claims and a kind of realism . . . Well, I think my attitudes have grown up a lot.'

In the full flood of her maturity Iris Murdoch would like to feel that her novels stimulate and entertain a varied audience, and she has no interest in writing for a literary elite. 'I'd like to think that lots of people read them, if only to escape from their troubles. After all, why not ?Some sort of enlargement of view as a novel has gives you another world into which you look, and you realise that people who are quite different from yourself are struggling along and having their troubles. I think novels are very good for people, even bad novels ... certainly much better than television which I abominate.'

For herself she reads few of her contemporaries, preferring the larger structure of the nineteenth-century novel: novels in which people still had a sense of religion and took prayer as a matter of course. That prayer has vanished is one of her regrets of modern life. A keen admirer of Henry James, she considers she is moving away from his influence. She would like to put more incidental characters in her novels, as Dickens does, and tease the plot apart more if it is possible. 'I'd rather be like Dickens or Dostoevsky, or Proust even—these are the great models, but of course one is just a tiny creature trying to cope in the shadow of these great mountains.'

Previous page

Previous page