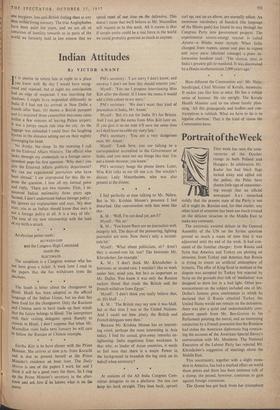

Demonstration Difficulty

By RICHARD H. ROVERE

No doubt the President would be delighted to visit with the Queen at any time, but her arrival last week must have seemed especially felicitous to him. It gave him a respite from sputnik and Syria and Little Rock and all of the people who have been making his life miserable these last few

weeks. Best of all, it enabled him to cancel his Wednesday news conference. The Queen was not due until Thursday, but everyone understands that a royal visit takes a lot of tidying up around the house and extra shopping and the rest, so no one accused the President of simple evasion when he allowed the administration to be spoken for by Mr. Dulles, who moved his own news conference to the hour when the President usually holds the floor. Mr. Dulles put his foot in his mouth a good half-dozen times, but the papers

were so full of Her Majesty that this received relatively little notice—in the United States any- way.

The press, too, was happy about the timing of the Queen's visit, and for reasons similar to Mr. Eisenhower's. She graced and brightened otherwise dark front pages. Not since the World Series have we had legitimate news headlines that didn't in one way or another use the rhetoric of defeat and disaster.

The press gave the Queen a great advance play,

and it was perhaps because of this, or partly be- cause of it, that the public response initially seemed rather limp. In Washington, for two or three days before her arrival, the newspapers were saying that a million people would greet her as she came into town. (A million would of necessity include tens of thousands from fairly distant places, for Washington alone could not produce a crowd that large.) The police main- tained that in fact a million did turn out, but the correspondents covering the event formed the opinion that a million was about five times the actual number. To my inexpert eye, surveying part of the show from a room in the Willard Hotel, smack in the centre of the city, the crowd seemed thin and it was assuredly undemonstra- tive. It may be that this was because the build-up was too great. Reading that there were to be a million people on the streets of Washington, many who otherwise might have come out may have decided not to become part of such a throng; they determined, perhaps, to put their comfort above their curiosity or their desire to honour the Queen. Many glasses may have been raised

N" York to her by admirers cosily settled before a' tell vision set.

I suspect, though, that it was more than matter of too great a press build-up. in this country, certainly, all demonstrations and cere' monies seem lately to have been diminished interest and meaning and quality. As we watched the Queen come into town, a friend of n remarked how the main part of the procession looked more than anything else like a gangster funeral in Chicago thirty years ago. It was just a procession of big, black automobiles driving along at five miles an hour. The car in which the Queen, Prince Philip and the President rode had a transparent top of Plexiglass, or whatever the stuff is, but it cut off much of the view and everything else was opaque. The Cadillacs could as well have held Owney Madden and Bel Frenchy De Mange as the illustrious figures re' ported to be inside. And as a matter of fact, such figures arc more exciting than Queens and Presi' dents nowadays, for through television we can see the tonsils of Queens and Presidents ■ nd know their voices and gestures as well as those of our friends. In this country, in the last decade or so, it has been enormously difficult for the politicians to fill auditoriums even when the attraction has been Dwight Eisenhower or A(

dlai Stevenson or Douglas MacArthur. It is the same with parades. Why should anyone stand on his feet and crane his neck to see a half-dozen prime ministers and cabinet members ride bY in some black sedans?

Some awareness of the difficulty affects the participants. At the reception given the Queen bY the Washington press (the press guilds and or- ganisations, which sometimes perform as if theY were agencies of American sovereignty rather than voluntary associations of citizens, sponsored the reception), she said in her prepared speech: 'I am well aware that this visit has probably given you a lot of extra work. . . .' Indeed, it was a lot of extra work, and only that, for most of those present, and the Queen was well advised to acknowledge this. If complete candour could have been afforded, she might have gone on to put the correspondents in their place by saying that it was more extra work for her (fifteen hun- dred hands to shake) than for anyone.

Of course, 1 may well be mistaken in the im- pression of over-all dreariness I have been getting from this event. Perhaps it does help in ways obscure to my poor vision to secure and tighten the bonds. In any case, it does nothing to loosen them. At this juncture there is in this country,

one imagines, less anti-British feeling than at any time within-living memory. The true Anglophobes have been quiet for years, and we are all so conscious of hostility towards us in parts of the world we formerly held in low esteem that we spend most of our time on the defensive. This doesn't mean that we'll behave as Mr. Macmillan will request us to this week. All it means is that if simple amity could be a real force in the world we could, probably generate as much as anyone.

Previous page

Previous page