TEN YEARS OF BRITISH BANKING.

BY SIR D. DRUMMOND FRASER, K.B.E., M.Com.

Iv one reviews the banking position to-day and compares it with the position in pre-War days, certain changes leap at once to the eye. The resources of the banks have increased beyond the highest flights of pre-War contemplation. Branches whose development was stationary during the War have sprung up in all directions during the last five years. British bankers have thrown themselves into the financial reconstruction of the Continent ; and banks have extended direct and indirect interest in overseas banking. Amalgamations have given place to affiliations. Banking capital has been added to, while banking names have been subtracted from. Gold coin has vanished from public use, and notes have come in to replace it. Gold coin in circulation and in the banks has been concentrated in the Bank of England. And the rise in prices was checked by the adoption of the banking principle of day-by-day borrowing.

The aggregate assets of the banks—Bank of England, English, Scots, and Irish banks—and of the currency notes are double the pre-War figure and exceed £3,000 million (December, 1923). The number of individual banks, owing to amalgamations, is less ; but the increase in the number of branches is from 7,423 to 11,394. This signifies an advantage to the public, because the compe- tition is keener than it was through the increased number of branches, which have intensified the penetration of banking resources throughout the country. The shortening of the names of the banks is another post-War change. This has been done to suit the convenience of the public. This measure is a typical indication of the present demo- cratic tendency. To the general public it is merely a shortening of irksome titles. But to the banks it is a concession to public demand at a somewhat costly initial price.

The era of amalgamations has now passed and has been replaced by the era of affiliations. While bank amalgama- tions meant a complete absorption of the assets and liabilities of the bank purchased, including the share capital, affiliations mean the obtaining of a controlling interest in the bank affiliated through the exchange, but not the extinction of the shares.

Among the English banks there are two outstanding examples of affiliation : Messrs. Coutts—one of the London clearing banks—affiliated with the National Provincial Bank ; and the Union Bank of Manchester with Barclays Bank. Among the Scots banks, the British Linen Bank affiliated with Barclays Bank ; the Clydesdale Bank and the North of Scotland Bank with the Midland Bank ; and the National Bank of Scotland with Lloyds Bank. Among the Irish banks, the Belfast Banking Company affiliated with the Midland Bank ; and the Ulster Bank with the Westminster Bank. As the other affiliations are with overseas banks they do not come within the scope of this article. The aggregate assets of the British overseas banks exceed £1,500 million. These affiliations have added to the investments of the Five Big Banks. They are represented by the shares of the banks affiliated, on the one hand; on the other hand, the liabilities have been increased by the capital issued in exchange for these shares. The net result is that there is an increase in banking capital as against a decrease when banks are amalgamated. This increase in capital and reserve fund in connexion with the Five Big Banks is approximately £25 million.

There is no doubt that amalgamations had reached their limit, which meant that the advantages to the public had reached their peak. Consequently, it was to the interest of the public to put- an end to these stupendous amalgamations, which had so splendidJy fulfilled their purpose. There has been another change in the banking system , in the form of new additional capital issues, which have been raised by the London Clearing Banks in new money from investors, in the shape of shares fully paid up. There is one exception, namely Lloyds; which, in issuing new capital, followed the old precedent of issuing shares not fully paid up. Barclays may also be called an exception in another direction, as they have made all their shares fully paid up by using their own resources to enable them to do so. The new capital raised in this way plus premium on the shares is approximately £20 million, exclusive of the increase in Barclays due to the paying up of the uncalled liability.

Undoubtedly the dominating influence in British banking to-day is the nine London Clearing Banks, whose aggregate resources were £2,000 million, at December, 1923. These are : the Bank of Liverpool and Martins, Barclays, Coutts, Glyn Mills, Lloyds, Midland, National Provincial, Westminster, Williams Deacons—to which must be added the National Bank, whose figures I have separated, because its main business is Irish.

One district alone has remained almost untouched by the centralizing influence ; and that is Manchester. With the exception of the Union Bank of Manchester, already referred to, Manchester banks have retained their local control, because their resources have proved adequate to the needs of their public ; and it has therefore been in the interest of this public of Greater Manchester that the control should not have been removed to London. I refer to the District Bank, which will be the first joint stock deposit bank in England to celebrate its centenary in 1929 (When the District Bank was approached by Lloyds, the Manchester public rose as one man to retain their best beloved bank) ; the Lancashire and Yorkshire Bank, of which the nucleus of its business was obtained by the absorption of the Manchester branch of a London bank (When the Lancashire and Yorkshire Bank was approached by Parrs—now the Westminster Bank—the public would have none of it) ; the Manchester and County Bank, which was formed in 1866 for the sole purpose of actively competing with the District Bank. The resources of these three banks at December, 1923, were 1114 million. To these ought to be added the resources of the Bank of Liverpool and Martins and the Williams Deacons Bank, whose main business and chief control are in the district of Greater Manchester : both London Clearing Banks, the figures of which are included in the London totals. The aggregate total assets of the Scots and Irish banks, the National Bank, the Union Bank of Manchester, the five West End private banks and the Yorkshire Penny Bank (which is owned by the English joint stock banks) represent £600 million. This leaves £300 million, which are the assets of the currency note issue of the Treasury. What do the total resources of £3,000 million of the banks consist of? First and foremost, accommodation granted to traders for legitimate trade ; and secondly, a strong cash basis, money at call and investments. The larger portion of the investments forms an asset which can be quickly turned into cash, so long as the Govern- ment issue an attractive security on tap to replace other Government securities and maintain an adequate sinking fund. The percentage of the accommodation granted to traders in the form of advances and disconnti-ng of bills for productive purposes to the deposit liability is the bankers' chief guide, enabling them to control the expansion and contraction of bank money for legitimate trade. This is the most comprehensive, as well as the biggest, item on the assets side of the banks. The dis- .enunting of bills has a quicker influence on the fluctuations of expansion and contraction of bank money than bank advane,Ps, because the former is more sensitive to and more in sympathy with the fluctuations in the orderly mar- keting of goods. If this combined ratio of advances and discounts is closely watched and efficiently controlled, the ratios of cash, call money and investments auto- .matically adjust themselves into their proper proportions . to the deposit liability. It is from advances and discounts that the traders can depend upon the solidity of banks • for purposes of practical usefulness. This solidity can only be attained if the proportion of cash, call money and investments to the liability is adequately safeguarded. This safeguarding demands a certain elasticity. This • elasticity must ultimately depend upon the bankers' • bank, the Bank of England. But it is to the interest of the public that the banks should render it as easy as • possible for the Bank of raglan(' to create this elasticity by not leaning too much on the Bank of England. They will be in this position if they maintain a. strong cash basis with a, firm second line of defence in the form of „money at call and short notice. To-day the banks have a third line of defence.: viz., Government security 'maturing at short dates.

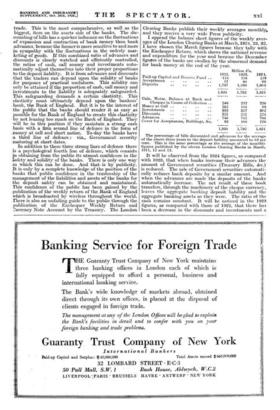

In addition to these three strong lines of defence there is a psychological fourth line of defence, which consists in obtaining from the public its utmost confidence in the tafety and solidity of the banks. There is only one way in which this can be done. And that- is by publicity. It is only by a complete knowledge of the position of the banks that public confidence in the trusteeship of the management of the liabilities and assets of the banks for the deposit safety can be obtained and maintained. This confidence of the public has been gained by the publication of the weekly return of the Bank of England which is broadcasted by wireless throughout the world. There is also an unfailing guide to the public through the publication of the Exchequer Weekly Return and Burreney Note Account by the Treasury. The London Clearing Banks publish their weekly averages monthly. and they receive a very wide Press publicity. I append the balance sheet figures of the weekly aver- ages of the London Clearing Banks at March, 1924, 23, 22. I have chosen the March figures because they tally with the Exchequer Return, which shows the national revenue and expenditure for the year and because the December figures of the banks are swollen by the abnormal demand for bank money at the end of the year.

Paid-up Capital and Reserve Fund .. Acceptances . • - • • • • Deposits •• •• •• 1922. -116 57 1,747 Million I's.

1923.

116 80 1,596 1924.

1.19 99 1,603

1,920 1,792 1,821 Coin, Notes, Balance at Bank and Cheques in Course of Collection .. 246 232 '230 Money at Call 102 104 93 In.vestments • • 393 357 362 Discounts Advances 951 746 251 742 224

786

Cover for Acceptances, Buildings, &o. 82 106 126

1,920 1,792 1,821 The percentage of bills discounted and advances for the average of the above three years to the deposit liability amounted to 63 per cent. This is the same percentage as the average of the monthly figures published by the eleven London Clearing Banks in March, 1911, 12 and 13.

It will be observed from the 1924 figures, as compared with 1923, that when banks increase their advances the amount of Government securities (Treasury Bills, .&c.) is reduced. The sale of Government securities automati- cally reduces bank deposits by a similar amount. And when the advances are made the deposits of the banks automatically increase. The net result of these book transfers, through the machinery of the cheque currency, leaves the aggregate banking deposit liability and the aggregate banking assets as they were. The ratio of the cash remains constant. It will be noticed in the 1923 figures, as compared with those of 1922, that there has been a. decrease in the discounts and investments and a corresponding decrease in the deposit liability. Had the Government security been replaced by commercial bills or advances there would have been no contraction in either the aggregate deposit liability or in the aggregate assets. But owing to trade inactivity there was not a sufficient demand for the advances and discounts of com- mercial bills to make up the reduction in Treasury Bills and short-dated Government security. This is a genuine example of monetary deflation, for the mildness of which we have, to thank the banking principle of continuous day-by-day borrowing, which was adopted during the War. By monetary deflation I mean bank money re- placed by the redemption of Government securities out of money found by the taxpayer. It is quite obvious from the above figures that the banks have the capacity and the resources to finance traders for productivity by allowing Treasury bills and ether short-dated Government securities to run off at maturity. But this capacity, of course, has a limit. When investors—i.e., depositors—are satiated, the limit is determined by the capacity of the Government to create bank money to meet these obligations. There is no doubt that a period of extensive trade revival is about to set in. And the question will arise as to how far genuine revival operations should be financed by bank money. Personally I hold that banks will be well able to continue the fine work they did in upholding the credit of the country during the difficult war period, by granting liberal accommodation on reasonable terms calculated to assist and not to check industry. Accom- modation at a reasonable rate of interest would take a comparatively small portion of the resources of 13,000 million. Therefore the principle of raising and lowering the rate of interest for contraction and expansion of bank money would remain unhampered and effective in preventing undue inflation or deflation, so long as inves- tors (depositors) purchased Government securities which the banks are realizing. The inflation caused by the Government borrowing bank money to finance the War and by traders borrowing bank money to finance the world-wide trade boom after the War created an expansion of bank credit and currency for the first period of War finance inflation-1913-1918- as represented by the Floating Debt of 11,500 million. This Floating Debt caused an equivalent increase in the bank and currency note assets, because the £1,500 million of borrowed money spent by the Government had not been assimilated by the people in the .form of Government investments, but had remained as manufactured money. The danger of this Floating Debt being turned quickly into inflationary currency or bank credit has been removed by the transfer of bills into bonds held by investors. The actual transfer of bills into bonds for the three years ending March, 1924, amounted to /547 million. There has been a further decrease in this menace through the cessation of borrowing by the Government from the Bank of England, with the exception of an occasional overdraft, to meet payments of interest for short periods. This overdraft is now provided by a Government Department instead of the Bank of England and therefore forms part of the basis of our financial machinery. The change was fully explained in the House of Commons by the Chancellor of the Exchequer when the alteration was made. But this is not the whole tale of Government borrowing during the War. The National Debt was increased by £5,500 million in addition to the Floating Debt of /1,500 million. £1,000 million of this was an external debt due to America. This has now been funded and has reduced the annual cost of the debt payable by instalments, to the equivalent of 14 per cent. per annum, of saving in interest. Of the remainder- 14,500 million—no less than /3,000 million was raised in the calendar years of 1917 and 1918 by means of a continuous loan represented by the 5 per cent. War Loan, National War Bonds and Savings Certificates. This money was found by the people direct and therefore day by day transferred the purchasing power of the individual to the Government. The hitherto continuous rise in prices was not only summarily arrested, but was actually reduced by this continuous form of borrowing which caused no upheavals in the investment market. Had it not been for this sane, sound policy of Mr. Bonar Law's there would have been double the inflation that there has actually been. The arresting of the con- tinuous rise in prices through this continuous borrowing policy is Clearly seen by the curves plotting the price level of this country, the United States of America and France. This is an outstanding testimony to the effect of a sound financial policy forced upon the Government by a banker for War finance. The inflationary borrowing of traders for the world trade boom-1918-1920- increased the bank assets by £800 million, which has since been reduced by /300 million.Notes, acceptances and other bank accommodation have each been reduced by £100 million. The remainder has been absorbed in the credit used for productive purposes. A special feature in the banking system to-day, compared with the pre-War system, is the concentration of the gold reserve in the Bank of England and the Treasury, which amounts to £150 million. This £150 million has replaced the Bank of England pre-War gold reserve of £30 million, the £40 million held by the other banks, which has been transferred to the Bank of England (the other banks holding notes instead), and the £80 million pre-War gold coin in circulation, which has been replaced • by currency notes. It is a greater national economy to have a gold reserve centralized than to have the gold in circulation. This concentrated gold is the cash base upon which our national credit is built. There is only one defect and that is the excessive amount of Government securities which have to lie idle for the purpose of covering an excessive issue of currency notes, owing to the restrictive use of cheques for small amounts, because of the twopenny stamp duty.

Surely the time has now arrived- the currency note issue 'of the Treasury should b amalgamated with the Bank of 'England note isiue, so that the whole of the currency of the country should be under one control —that of our central bank, the Bank of England! This is the lead which the reconstruction of public finance in Central Europe is giving to the world. This could be done by a short Act of Parliament to remove the legal disability of the Bank of England to issue notes below £5. It would also bring the question of fixing the limit of the fiduciary issue and the cost of manage- ment within the range of practical politics. The Bank of England would then have complete control of bank money for the finance of trade. The provision already existing in the currency note Act for the elasticity required to meet special necessities could be incorporated in the arrangements made.

The percentage of the cash, 8ro., money at call and investments for the London Clearing Banks' average of the three years 1922-23-24 represents 43 per cent of the deposit liability. Since the War, the tendency has been for the banks to make a fuller use of a portion of the Government securities as part of the cash resources. The key to the soundness of this situation is the regular, consistent redemption of Government debt. The Govern- ment has met this position by the adoption of the New Sinking Fund of 145 million a year, which is applied for the redemption of Government securities week by week. Any attempt to reduce debt at too quick a rate is just as harmful as not reducing it at all, because in the former case it is too great a burden on the tax- payer, and in the latter case our national credit is jeopardized.

The corresponding aggregate liability of the banks and Treasury Note Account to the assets of 13,000 million is made up approximately as follows :- Deposits £2,340 million = 78 per cent. Notes . . £480 „ = 16 „ Capital and Reserve Fund of the

Banks .. £180 ,; = 6 ,, £3,000 „ = 100 per cent.

I have excluded the smallest item which appears on both sides, viz.,. acceptances.

I once again urge the removal of the twopenny stamp duty on cheques, which restricts the use of cheques for small amounts, in order that the excessive note issue of 1480 million may be reduced and the deposit

. .

increased by a corresponding amount. This transfer of credit would leave the aggregate assets of the banks and the Currency Note Account untouched. In addition to the provision of the Sinking Fund out of taxation to meet annual redemption of debt week by week, I suggest an issue of Post Office bonds of 25 and multiples which week by week would meet other Government maturing debt. This would spread the Government debt among the largest number of individuals and would relieve the banks of some of the Government securities with which they have been saddled in con- nexion with War finance. These securities tie up money which would thus be released to lend to the traders of the country. Such an issue would be a complement to the present Bank of England issue of Treasury Bonds by tender week by week and would replace bad money by good. During the period under review there have been several institutions which, under the name of "bank," have attracted deposits to the ruin of small depositors. May I offer as a final suggestion that the long-prepared Hill defining the word " bank " be forced through Parliament in the public interest ?

Previous page

Previous page