National Trust

Injustice and commercialism

Yvonne Brock

When my husband came out of the Navy in the mid-'fifties he applied to the National Trust for a custodianship of one of their properties. These posts were — and are — difficult to come by, as the number of ' staffed' properties is few. Most of the smaller houses are tenanted, by either a member of the donor's family or an outsider, who pays for the privilege of living in attractive surroundings and opens his house to the public on a more limited basis than do the staffed properties.

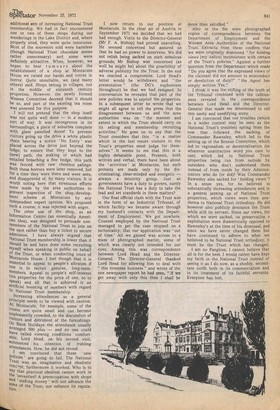

Our opportunity came in 1958 on the death of the first Custodian of Montacute House, near Yeovil in Somerset. We hastened to inspect the place, saw it first on a dull, dark November day, and loved it on sight. Montacute, for those who do not know it, is a gem of Elizabethan architecture, built in warm yellow stone from neighbouring Ham Hill, and standing in fine formal gardens with park beyond.

We started at the princely salary of £450 per annum (joint) but as this carried rentand rates-free accommodation in a wing of the house, with lighting and heating also provided free, we reckoned that with our small private means and what we each earned by such fringe activities as writing and broadcasting we could manage. In fact, we were able to live in modest comfort and to run a, car. We were later retitled Administrators, and our joint salary by 1971 was £700.

We were appointed by two elder statesmen of the Trust, one of them the then Area Representative (I will explain this term later). A fair paraphrase of what was said to us was that we should aim to present Montacute as a well run country house; in addition we should live in the house and regard it as our home. The former requirement involved much compromise. Well run country houses are not commonly overrun with primary schools, nor do they suffer Bank Holidays in the way that the rest of us do. Nevertheless, by showing Montacute for what it was — a fine house in a beautiful setting — and by a careful selection of part-time Guides, so that there were no jokey or inaccurate tours of the house, I think we achieved something. The second requirement — to regard Montacute as our home — caused no difficulty whatsoever. A large house, it yet has a remarkable warmth and intimacy, and house and grounds provided an idyllic setting for many concerts and dramatic recitals, some initiated by ourselves and some run in conjunction with outside organisations.

The public, as the widow of our predecessor remarked, can be a hard taskmaster, and indeed from time to time we encountered rudeness and unreasonableness. Children (small) and dogs (of any size) were the biggest menaces, as parents/owners often tended to react violently to mild requests for some kind of control. A type of letter with which National Trust Headquarters is all too familiar was occasionally sent to us. In content it ran roughly thus " . . nasty man stopped Kevin eating his iced lolly in the Great Hall . . . my wife cried all the way home . . . wish to resign our membership of the National Trust." However, these were more than offset by the appreciation which was general and, heartwarming.

The public could be hard taskmasters; so could the area authorities, of which some account must now be given. The main difficulty was a division of authority which was decidedly blurred at the edges. 'In our case (Wessex Area) the Area Agent and his staff operated from Stourhead and were responsible for finance, upkeep and repairs. The Area Representative resided at Dyrham Park and had ultimate responsibility for the presentation of properties in his area, the acceptance and placing of loans or gifts — in short, the aesthetic as opposed to the practical and financial side of things. To say that these two authorities did not always hit it off would be a masterpiece of understatement, and all too often we found ourselves the luckless middlemen in various disputes. However, so long as the Representative was in the ascendancy, so to speak, all was comparatively well.

Trouble was to come however in the uncompromising person of Commander Conrad Rawnsley (a grandson of one of the three founders of the National Trust) who was appointed by the Trust as Director of Enterprise Neptune in the early 'sixties and sacked by them a few years later. At a press conference, while still in the Trust's employment, he made a number of accusations against his employers. including those of inefficiency, nepotism and bad faith. In the hope of clearing the air (or of washing off the mud that had been flung) the Trust undertook to look into its own affairs, and the Benson Committee, set up for this purpose, made a number of recommendations.

While the Committee's understanding of so strange an animal as the National Trust was necessarily limited, it did correctly pinpoint the remoteness of HQ in London from the regions, and therefore recommended decentralisation. It also saw the anomalies of the divided command and, apparently seeing the representative as a sort of dilettante (true, in some regions they were honorary or even lacking altogether), recommended the setting up of committees in each region, to which the representative should eventually become secretary. This, to my mind, was unfortunate. It upset the system of checks and balances and led to a degree of 'agent power.' Unfortunately also, the committees were given executive authority, instead of merely acting in an advisory capacity. After all, the members were only amateurs, part-timers, chosen in a haphazard sort of way. Herein lay the roots of our subsequent troubles.

We awaited the formation of our Committee in some trepidation. There had, so our predecessor's widow informed us,

been a Wessex Committee some years ago — "but it was such a nuisance that they

got rid of it "! Much would obviously depend upon the personality of the Chairman, and we longed for someone of the calibre of, say, Sir John Betjeman. In the end we got Lord Head; formerly Anthony Head, retired brigadier and politician.

We met him twice. The first occasion, in the summer of 1970, was social, the Agent

having brought him over to meet us, and he looked briefly at the house. He showed little interest in its architecture or contents, but seemed preoccupied with numbers of visitors and how these could be increased. This was in the summer of 1970. On his second visit, in May 1971, I did not actually meet him but (from the house) heard him shouting at my husband (who had met him in the gardens) that he must not "whip up opposition " against the " new policies." We never saw or heard from any other member of his committee, though we were promised (or threatened with) a colonel "with special responsibility for Montacute."

Our final contact with Lord Head was in early October, 1971, when we received a copy of a letter dated September 20, 1971, giving us the sack. We were thanked for out services " over the past eight years" (actually thirteen) but Lord Head felt that we might be " resistant to changes in policy" and that therefore it would be "unfair " to continue. He regretted that he had found it necessary to "terminate you and your wife's employment" (sic) and required us to leave Montacute by the end of March, 1972.

What sense could one make of this illiterate, illogical and inaccurate communication, timed to reach us during our absence abroad on holiday, the original of which never reached us at all? Why was there no warning, no consultation? There were no complaints against our administration, nor could we possibly in our position have been "resistant to changes in policy." "Concerned in the implementation of new policies as they applied to Montacute," the property for which we were responsible, would accurately repre• sent our attitude. We had a duty to advise and to warn, and this we did, and no more. To those members of the public (mostlY also members of the National Trust) wh° complained to us about the changes at Montacute we gave the advice to write to Head Office in London stating their objections. We actively discouraged letters to the press or resignation of National Trust membership; so much for Lord Head's accusations on his second visit that we had "whipped up opposition" to the new policies. What then were these new policies, and how did they affect Montacute? After ' Benson' we began to hear a good deal about shops at "selected properties " and a policy of increasing attendances with the

additional aim of increasing National Trust membership. We had in fact encountered one Or two of these shops during our wanderings in the Lake District and, where properly sited, they were quite innocuous. Most of the souvenirs sold were harmless (though National Trust chocolate seems rather unnecessary) and some were definitely attractive. When, however, we began to hear rumours about the establishment of a shop at Montacute House we raised our hands and voices in horror. Quite unsuitable, we (and many others) said. Shops belong in villages, not in the middle of sixteenth century properties. However, the newly formed Wessex Committee decreed that it should be so, and part of the existing tea room was annexed for this purpose.

I will not pretend that the shop itself was not quite well done — in a modern sort of way. It was incongruous in its surroundings; a piece of suburbia complete With glass panelled doors! To prevent visitors going up the drive a white plastic chain bearing a notice ' No Entry' was placed across the drive just beyond the lodge; to ensure that they kept to the (new) path, the making of which had entailed breaching a fine hedge, this path was fenced with raw chestnut palings. Both these horrors were later removed, but for a time they were there and were seen, and disapproved of, by many visitors. It is worth noting here that strenuous efforts were made by the area authorities to Prevent inspection of the shop/development scheme at Montacute by any Independent expert opinion. We proposed such a course; it was rejected with anger. The other use of the shop, as an Information Centre (an essentially American idea), was designed to persuade nonmembers of the National Trust to join on the spot rather than buy a ticket to secure admission. I have always argued that National Trust membership is lower than it should be and have done some recruiting myself when speaking in public on behalf of the Trust, or when conducting tours of Montacute House. I feel though that it is essential to appeal to people's altruism if one is to recruit genuine, long-termmembers. Appeal to people's self-interest (six properties for the price of one, so to sPeak) and all that is achieved is an artificial boosting of numbers with regard to National Trust membership. •

Increasing attendances as a general Principle needs to be viewed with caution. At Montacute, for example, some of the rooms are quite small and can . become unpleasantly crowded, to the discomfort of visitors and detriment of the furnishings. On Bank Holidays the attendance usually averaged 500 plus — and no one could have called viewing conditions comfortable. Lord Head, on his second visit, announced his intention of trebling attendances. How, he did not reveal. I. am convinced that these 'new Policies ' are going to fail. The National Trust was an imaginative and idealistic c'pnc`Tt; furthermore it worked. Who is to saY that practical idealism cannot work in the 'seventies? A preoccupation with shops an. d ' making money' will not advance the alms of the Trust, nor enhance its reputation.

I now return to our position at Montacute. In the clear air of Austria in September 1971 we decided that we had had enough. Visits to the Director-General (Mr F. A. Bishop) had proved unavailing. He seemed concerned but assured us that he had no power to intervene. We did not relish being sacked on such nebulous grounds; Mr Bishop was concerned (as well he might be) about the possibility of adverse publicity for the Trust. In the end we reached a compromise. Lord Head's letter would be withdrawn and "the presentation" (the DG's euphemism throughout) be that we had resigned. In conversation he revealed that part of the new policies was to exploit the properties. In a subsequent letter he wrote that we might all agree to tell the press that the disagreement between us and the area authorities was on "the manner and extent in which the Trust should carry on its selling and membership recruiting activities." He goes on to say that the Trust considers that this " is a matter which in the last resort visitors to the Trust's properties must judge for themselves." It seems to me that this is a highly 'debatable point. Protests, both written and verbal, there have been about the ' activities ' at Montacute, but such protests are made only by the discriminating, clear-minded and energetic — always a minority group. Just as governments have a duty to govern, surely the National Trust has a duty to take the lead and set standards in these matters?

Our final official clash with the Trust was in the form of an Industrial Tribunal, of which facility •we became aware through my husband's contacts with the Department of Employment. We got nowhere. Counsel employed by the National Trust managed to get the case stopped on a technicality; that our application was 'out of time.' All we gained was access to a mass of photographed matter, some of which was clearly not intended for our eyes. Among this was correspondence between Lord Head and the DirectorGeneral. The Director-General thanked Lord Head for allowing him to deal with "this tiresome business" and wrote of the one newspaper report he had seen, "If we get away with only this then I shall be

more than satisfied."

Also in the file were photographed copies of correspondence between the Department of Employment and the Wessex Area Authorities of the National Trust. Extracts from these confirm that we were originally dismissed "for holding views (my italics) inconsistent with certain of the Trust's policies." Against a further question from the Department which reads "Do you agree that the expressed views of the claimant did not amount to misconduct or dereliction of duty?" " the Agent has simply written Yes."

I think it was the stifling of the truth at the Tribunal combined with the callousness revealed in the correspondence between Lord Head and the DirectorGeneral that made me determined to tell this nasty and unedifying story.

I am convinced that our troubles (which in a wider context may be seen as the National Trust's troubles) spring from the row that followed the sacking of Commander Rawnsley, which led to the setting up of the Benson Committee, which led to regionalism or decentralisation (or whatever unattractive word you care to use), which led to National Trust properties being run from outside by outsiders who don't understand, them instead of from inside by their Administrators who do (or did)! Was Commander Rawnsley also sacked for 'holding views '? In a sense yes, for he believed in substantially increasing attendances and, in a general jazzing up of National Trust properties, which views were then anathema to National Trust orthodoxy. He did however also publicly denounce the Trust while still its servant. Since our views, for which we were sacked, on preservation v exploitation were diametrically opposed to' Rawnsley's at the time of his dismissal, and since we have never changed them but have continued to adhere to what we believed to be National Trust orthodoxy, it must be the Trust which has changed.

I am no Pangloss; I cannot believe that all is for the best. I would rather have kept my faith in the National Trust instead of seeing it as I do now, as a shoddy, secondrate outfit both in its commercialism and in its treatment of its faithful servants. Everyone has lost.

Previous page

Previous page