Pleasure Gardens

The spirit of Vauxhall

Alan Powers

ineteenth-century urban growth and the spread of middle-class morality irrevoc- ably changed the character of the London- er's recreations. The Georgian pleasure gardens, of which Vauxhall and Ranelagh are the best-remembered, were bank- rupted, acquired for building or closed down by the magistrates, leaving no suc- cessors for the 20th century. After the final closure of Vauxhall in 1859, there re-

N

mained Cremorne, at Chelsea, whose fire- works inspired Whistler, and the notorious Rosherville.

The buildings, which replaced them are an indication of the social transformation. Spa Fields, the resort of 'journeymen, tailors, hairdressers, milliners and servant maids', provided the site for the Countess of Huntingdon's Chapel as early as 1776, and some post-war flats by Berthold Lubetkin now cover another part of the ground. Finch's Grotto in Southwark was demolished to make a skittle alley in 1773, and later the pub on the site of this musical mecca carried the inscription: Here Herbs did grow And Flowers sweet, But now tis call'd Saint George's Street.

The Dog and Duck, nearby, enjoyed by 'the children of poverty, irregularity and distress', was demolished in 1811 for the building of the Bethlehem Hospital (now the Imperial War Museum).

In spite of the lurid reputations of some of the gardens, they provided the innocent pleasure of eating, drinking, dancing and listening to music out of doors, amidst trees, flowers and ornamental buildings. On a summer night in London today, these things are unobtainable. In their place, the Victorian age created the Crystal Palace at Sydenham and the Alexandra Palace, great creations of democracy, but lacking the intimate human quality that must have made even Vauxhall, the biggest of the original gardens, so attractive. It was said that 'at no other London resort could the humours of every class of the community be watched with greater interest or amuse- ment.'

The tradition of the pleasure gardens was carried on in Scandinavia. The Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen were opened in 1843, with the approval of King Christian VIII who hoped thereby to keep the forces of liberalism at bay. Although much altered over the years, the gardens retain features like the Chinoiserie Theatre, with its peacock curtain, where there is an unbroken continuity of commedia dell' arte. There are imitations in the Nordic world, the only one of which I have visited being the Liseberg Gardens at Gothen- berg, where 'white-knuckle rides' and an elaborate flume-ride are combined with orderly outdoor dancing and restaurants in pleasant classical buildings.

London did make an attempt to revive the spirit of Vauxhall in the Festival Gardens at Battersea in 1951, intended by Gerald Barry to offset the seriousness of the main South Bank exhibition in the Festival of Britain. Designed by James Gardner, with help from John Piper, Osbert Lancaster and others, it had a theatre, dance tent, grotto and beer- gardens, as well as the tree-walk and the Emmett railway, the features most likely to be remembered. Unfortunately, the LCC sold its lease after three years, and the funfair predominated over gentler, old- fashioned amusements, until the last rem- nants were cleared away in the mid-1970s.

The original Vauxhall needed to be seen at night. By day, the decorations revealed themselves as painted canvas. The number of lamps, all illuminated at once, was one of the wonders of London, and the Dark

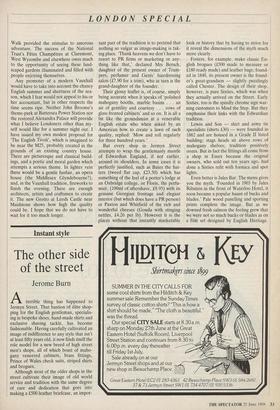

From The English Tivoli, a set of 16 hand-coloured lithographs in a box, by Alan Powers, published by Judd Street Gallery, London WC1

LONDON SPECIAL

Walk provided the stimulus to amorous adventure. The success of the National Trust's Fetes Champetres at Claremont, West Wycombe and elsewhere owes much to the opportunity of seeing these land- scaped gardens illuminated and filled with people enjoying themselves.

Any promoter of a modern Vauxhall would have to take into account the chancy English summer and shortness of the sea- son, which I fear would not appeal to his or her accountant, but in other respects the time seems ripe. Neither John Broome's theme-park at Battersea Power Station nor the restored Alexandra Palace will provide what I believe Londoners other than my- self would like for a summer night out. I have issued my own modest proposal for `The English Tivoli', which is imagined to be near the M25, probably created in the grounds of an existing country house. There are picturesque and classical build- ings, and a poetic and moral garden which attempts a serious theme. In lighter vein there would be a gentle funfair, an opera house (the Middlesex Glyndebourne?), and, in the Vauxhall tradition, fireworks to finish the evening. There are enough architects, artists and craftsmen to create it. The new Grotto at Leeds Castle near Maidstone shows how high the quality could be. I hope that we do not have to wait for it too much longer.

Previous page

Previous page