Pecksniffs

Gavin Stamp

The Image of the Architect Andrew Saint (Yale £9.95)

Achitects seldom lead very thrilling lives, so it is perhaps remarkable that members of the profession have provided the plots for three rather sensational films. There is Towering Inferno, of course: a flint

which tells us all we want to know about building skyscrapers. Then, less well known

and less about architecture, we have Girl on a Red Velvet Swing, a dramatisation of the true story of the murder of the great American classicist, Stanford White, in, 1906 by his mistress's admirer on the top 01 Madison Square Gardens — one of

McKim, Mead & White's own buildings.

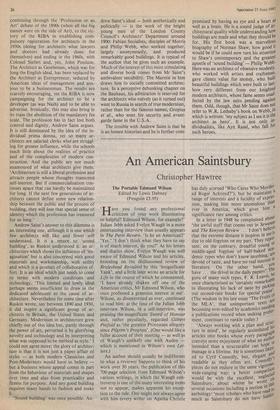

Finally there is The Fountainhead, the Mtn of the late Ayn Rand's eponymous novel of

1943, that American parable of the virtue of uncompromising individuality and the evil of collectivist conformity. This novel, illustrated by stills from the film, presents the theme of Andrew Saint's original and polemical study of the nature of the architect, for it epitomises the belief in the 'Architect as Hero', the architect as

creative artist, the architect as prima- donna, which has been dominant for the last two centuries — with many unfortunate

consequences. Ayn Rand's hero is Howard

Roark (Gary Cooper), an all-American, abrasive architect totally committed to a

pure, unsullied modernism. As a result he

gets no work, all the jobs going to corn- promising second-raters, but his talent Is

such that he is asked to 'ghost' for others when their Classical or Deco skyscrapers 80 out of fashion. But when one of Roark s gleaming, austere designs is altered in the

execution, he dynamites it. Such is integri- ty: no sympathy for the aspirations of the client, little understanding of the essentially compromising nature of the practice of ar- chitecture; for the architect is an artist and his vision is what must command admira- tion. The Fountainhead was very closely based on American architecture in the 1930s: so closely, indeed, that Ayn Rand had to deny that Howard Roark was his evident model,

Frank Lloyd Wright, the apostle of in- dividualism and of American character in architecture, who was wonderfullY egotistical and arrogant, who was also unorthodox and spent some years In the professional wilderness. Fortunately, Wright was a very great architect; for- tunately also, Mr Saint admires his work, for he nevertheless sees this idea of the Ar- chitect as Hero as partly responsible for the modern architect's neglect of the mundane, practical sides of his art and of his contempt for the ordinary public. The idea of the ar- chitect as an avant-garde, misunderstood artist has been used to justify a great many shoddy, badly designed, inefficient buildings.

The Architect as Hero is a modern inven- tion and the result of a wilfully Romantic misreading of history, Mr Saint believes. He explores this theme in an excellent chapter on 'Myth and the Mediaeval Ar- chitect' which is concerned with the still °Pen question of how the cathedrals were actually designed and built. Some guide books still repeat the idea that they were the creation of mediaeval clerics, although it is as unlikely that William of Wykeham or board of Walsingham sat at the drawing ooard as it is that the present Bishop of Bir- mingham or Dean of St Paul's could actual- ly design anything of beauty. Others, therefore, have searched for the mediaeval equivalents of modern architects. Goethe Paid homage to Erwin von Steinbach as the architect of Strassburg Cathedral (which he wasn't) in Von deurscher Baukunst while, More recently, John Harvey has searched diligently for the names of artisans and craftsmen recorded in connection with Gothic buildings. But were these men architects? Did they alone have sole conduct of the work? Pro- bably not There is an alternative inter- Pretation and one associated with Ruskin, Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. This is that mediaeval churches and the great cathedrals were the products of the collective efforts of artists and craftsmen, the creation of the craft guilds. This equally Romantic idea, which inspired such Vic- torian societies as the Art-Workers' Guild to bridge the gulf between architects and other crafts, clearly contains a strong ele- ment of obvious truth. The cathedrals must have been the product of the clever organisation of skills and labour, as in a modern industrial corporation. There need not have been one, and only one controlling hand, ,,This is an idea which evidently appeals to Mr Saint as he examines the way in which architects have sought independence and 13.°wcr through professional (that is, protec- tive) status and artistic eminence (that is, r master- builder, The humble role of master- which produced so much uniform- ly sensible building in the 18th century, is not one that suited Gilbert Scott, Lutyens be Basil Spence. As a result, the author realities architects have lost touch with the tealities of building in both Britain and the United States and their real power is declin- ing. (It is commonplace to erect a building without an architect in the U.S.A. and Possible — sometimes desireable? — here.) _

In England the story is one of amateurism, beginning with Mr Peck sniff, continuing through the 'Profession or an Art' debate of the 1890s (when all the big names were on the side of Art), to the vic- tory of the RIBA in establishing com- pulsory registration for architects in the 1930s (doing for architects what lawyers and doctors had already done for themselves) and ending in the 1960s, with Colonel Siefert and, yes, John Poulson. The Architect as Gentleman, which was for long the English ideal, has been replaced by the Architect as Entrepreneur, seduced by American ideas of management and anx- ious to be a businessman. The results are scarcely encouraging, yet the RIBA is now campaigning for the architect to be a developer (as was Nash) and to be able to advertise. Ironically, this may also bring in its train the abolition of the mandatory fee scale. The profession has in fact lost both control and dignity, Andrew Saint argues. It is still dominated by the idea of the in- dividual prima donna, yet so many ar- chitects are salaried clerks whd are struggl- ing for greater influence, while the schools teach little about the realities of practice and of the complexities of modern con- struction. And the public are not much enamoured of what architects give them. 'Architecture is still a liberal profession and attracts people whose thoughts transcend self-interest. But if commercialisation con- tinues apace that can hardly be maintained for long. If the next few generations of ar- chitects cannot define some new relation- ship between the public and the process of building, they will lose that special sense of identity which the profession has treasured for so long.'

Andrew Saint's answer to this dilemma is an interesting one, although it is one which few architects will like and fewer will understand. It is a return to 'sound building', as Ruskin understood it: an ar- chitecture which shows the influence of 'im- agination' but is also concerned with good materials and workmanship, with utility and which is a product of collaborative ef- fort. It is an ideal which just needs to come to terms with modern conditions and technology. 'This limited and lowly ideal perhaps seems insufficient to draw in the dedicated adolescent to the cause of ar- chitecture. Nevertheless for some time after Ruskin wrote, say between 1890 and 1930, it did inspire a significant group of ar- chitects in Britain, the United States and Germany. Modernism in architecture grew chiefly out of this idea but, partly through the power of art, perverted it by glorifying novelty and technology and by interpreting what was supposed to be method as style.' I could not agree more; the glory of architec- ture is that it is not just a paper affair of styles — as both modern Classicists and Post-Modernists would have us believe but a business whose appeal comes in part from the behaviour of materials and shapes over time and also from practicality and fitness for purpose. And any good building requires many hands to fashion and make it.

'Sound building' was once possible. An- drew Saint's ideal — both aesthetically and politically — is the work of the bright young men of the London County Council's Architects' Department around 1900: Fabian Socialists, disciples of Morris and Philip Webb, who worked together, largely anonymously, and produced remarkably good buildings. It is typical of the author that he gives such an example. Much of the interest of this most stimulating and diverse book comes from Mr Saint's ambivalent sensibility. The Marxist in him draws him to socially committed architec- ture. In a perceptive debunking chapter on the Bauhaus, his admiration is reserved for the architects who naively (as it turned out) went to Russia in search of true modernism, rather than for the famous names, Gropius et al., who went for security and avant- garde fame in the U.S.A.

The trouble with Andrew Saint is that he is an honest historian and he is further corn-

promised by having an eye and a heart as well as a brain. He is a sound judge of ar- chitectural quality while understanding how buildings are made and what they should be for. His first book was a marvellous biography of Norman Shaw; how good it would be if he could now turn his attention to Shaw's contemporary and the greatest apostle of 'sound building' — Philip Webb. Here was an architect of obsessive modesty, who worked with artists and craftsmen, gave clients value for money, who built beautiful buildings which were built to last: how very different from our knighted modern architects, whose fame seems unaf- fected by the law suits pending against them. Odd, though, that Mr Saint does not refer to W.R. Lethaby's book on Webb, in which is written: 'my subject as I see it is the architect as hero'. It is not only in dividualists, like Ayn Rand, who fall for such heroes.

Previous page

Previous page