Exhibitions

Bernini Scultore (Galleria Borghese, Rome, till 20 Sept)

Celebrating in style

Martin Gayford

The behaviour of travellers in modern Rome closely mimics that of mediaeval pil- grims. Certain spots, sacred to the gods of tourism, are densely — indeed often unbearably — packed with groups of votaries, each following a leader holding aloft a flag on a little stick. But much of the rest of the city, even in July, is blessedly uncrowded, especially the Baroque sites, ignored by the art lover in the street. That applies even in this, the 400th anniversary of the birth of Gianlorenzo Bernini, presid- ing spirit of Baroque Rome.

The Bernini anniversary is being celebrat- ed in style, however, at the Galleria Borgh- ese, in an exhibition which is also an examination of that museum itself: Bernini Scultore — La Nascita del Barocco in Casa Borghese. It is focused on the spectacularly precocious career of the young Bernini, at a time when his principle patron was Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the creator of the Villa Borghese, and owner of many of the most important works in the Borghese collection.

Bernini was one of the best examples of precocity in history, exceeded perhaps only by Mozart. In both cases, the reason was the same: a powerful push from a parent sublimating his own ambitions. Pietro Bernini, father of Gianlorenzo, was a mod- erately talented, reasonably successful sculptor. He delighted in, and encouraged, the talents of his son. When it was pointed out to him that Gianlorenzo was likely to overshadow his father, Pietro shrewdly remarked that, in that contest, 'he who loses, wins'.

For-his part, Gianlorenzo was producing notable bits of sculpture by the time he was in his mid-teens, and staggering displays of originality and virtuosity in his early twen- ties. Most of these sculptures have been reassembled for this exhibition.

The very earliest pieces Bernini pro- duced featured putti — at a time when he was not much older than a putto himself. The Goat Amalthea Suckled by the Infant Jupiter and a Satyr' might have been carved as early as 1611-12 (that is, when he was 13 or 14 years old). More satisfactory, less clumsy-looking, is the 'Putt° Bitten by a Dolphin', wailing in understandable dis- tress, on loan from Berlin. But both display in embryo Bemini's amazing ability to sug- gest the texture and consistency of different substances — the softness of chubby baby flesh, the hairiness of the goat — through the manipulation of hard, resistant marble.

A young man out to make his name, he went all out to stun through the sculpting of the apparently impossible. In 'The Mar- tyrdom of St Lawrence', another loan, he attempts to reproduce the flames licking the body of the tormented saint. It doesn't quite come off, the effect is a little reminis- cent of foam plastic, or extruded ice-cream — though the saint himself, piously turning his eyes to heaven with the plea that Rome be hinted into a more Christian place, is a success. And Bernini was still under 20 when he produced it.

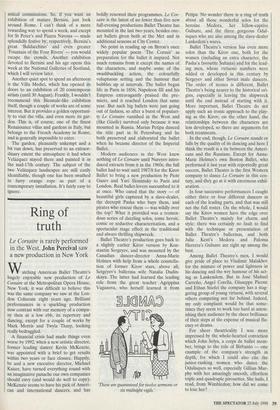

In the next few years he produced four full-size sculptural groups: 'The Flight from Troy', 'Pluto Abducting Proserpina', 'David' and 'Apollo and Daphne', each more astonishing than the last. The last is the most astonishing of all. It shows the very moment at which, after a lengthy chase, the god caught up with the nymph, and she prayed to Diana to be transformed into a less lust-inducing form. Her wish granted, she became a laurel tree.

Bernini is dealing with less than a moment, a split-second of metamorphosis. Daphne's fingers sprout twigs and leaves, her toes grow roots, bark encases her body. Her expression seems to freeze, the eyes glaze. All these utterly unsculptural sights and things are cut in marble (what could be more unsuited to treatment in stone than a leaf?).

It is a staggering display of skill, but that is not the real point. In fact, as Charles 'Apollo and Daphne; 1622-25 Avery points out in his book Bernini: Genius of the Baroque (Thames and Hud- son), now the best on the subject, a good deal of this vituoso carving was done by one Giuliano FineIli. Already, in his twen- ties, Bernini was too busy to execute every- thing himself and had to delegate — though he meanly withheld credit from Finelli. (A series of painted self-portraits suggests that Bernini could be formidable, not to say dictatorial.) But the idea, the design were his — and that is really the point. 'Apollo and Daphne' is a deliciously paradoxical object, a split-second solidified into stone. It is the sort of thing painters, not sculptors were supposed to do.

It is the same with the other groups. Pluto has just seized Proserpina, who is filled with horror and despair. A bluff look of satisfaction covers the face of the mus- cular god, as of a rugger player in the act of scoring a try. His brawny fingers dig into her soft flesh. Bemini's 'David', unlike Michelangelo's or Donatello's, who simply stand triumphantly, heroically, is at the point of loosening the fatal sling-shot, frowning with concentration.

These are miniature psychological dra- mas, subjects for a painter rather than a sculptor, you might think. And, indeed, Bemini was a sort of painter in stone. All these groups are supposed to be seen from a certain point of view, like a painting. He explicitly attempts to rival the power of paint to suggest texture, even colour. All this has made him unpopular with those who believe in the modernist doctrine of truth to materials. But the paradox of a three-dimensional picture, the magic of transformation, is part of the pleasure.

It made Bernini, among other things, one of the greatest portraitists in any medium. His bust of Scipione Borghese, displayed upstairs with some other portrait busts, equals Velazquez in its fixing of a mobile expression, a passing thought (the second version, done because of a flaw in the mar- ble of the first, is just a little less living).

This is a lovely, if slightly eccentric exhi- bition. The Beminis are scattered about so that it takes a while to discover them all; it is not immediately clear that there is another section upstairs among the picture collection. The exhibits, on the other hand, are beautifully lit, appropriately, since he himself was a master of lighting. It man- ages to reassemble nearly all the early Beminis not already at the Borghese — including an interesting oddity, the magnif- icently stuffed and tasselled mattress he sculpted for a classical hermaphrodite, prized by Cardinal Borghese, to lie on. The main absentee is the 'Neptune and Triton' from the V&A.

After his mid-twenties, Bernini stopped producing this sort of exquisite connois- seur's piece. In 1623 Urban VIII, like Scipi- one Borghese an ardent fan of the young sculptor, became pope. And from that day until his death at the age of 82, Bernini's energies were applied to papal and ecclesi- astical commissions. So, if you want an exhibition of mature Bernini, just look around Rome. I can't think of a more rewarding way to spend a week, and except for St Peter's and Piazza Navona — made splendidly festive by, respectively, Bernini's great `Baldacchino' and even greater 'Fountain of the Four Rivers' — you would escape the crowds. Another exhibition devoted to Bemini and his age opens this week at the National Galleries of Scotland, which I will review later.

Another quiet spot to spend an afternoon is the Villa Medici, which has opened its doors to an exhibition of 20 contemporar artists (until 30 August). Frankly, I wouldn't recommend this Biennale-like exhibition itself, though a couple of works are of some interest. But it provides a golden opportuni- ty to visit the villa, and even more its gar- den. This is, of course, one of the finest Renaissance villas and gardens in Italy, but belongs to the French Academy in Rome, and is generally impossible to enter.

The garden, pleasantly unkempt and a bit run down, has preserved to an extraor- dinary extent the atmosphere it had when Velazquez stayed there and painted it in the mid-17th century. The subject of the two Velazquez landscapes are still easily identifiable, though one has been swathed in furry orange rope as part of a contemporary installation. It's fairly easy to ignore.

Previous page

Previous page