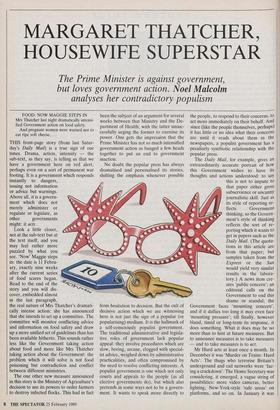

MARGARET THATCHER, HOUSEWIFE SUPERSTAR

The Prime Minister is against government,

but loves government action. Noel Malcolm

analyses her contradictory populism

FOOD: NOW MAGGIE STEPS IN Mrs Thatcher last night dramatically intensi- fied Government action on food safety.

And pregnant women were warned not to eat ripe soft cheese....

other governments might: it acts.

The one other new measure announced in this story is the Ministry of Agriculture's decision to use its powers to order farmers to destroy infected flocks. This had in fact been the subject of an argument for several weeks between that Ministry and the De- partment of Health, with the latter unsuc- cessfully urging the former to exercise its power. One gets the impression that the Prime Minister has not so much intensified government action as banged a few heads together to put an end to government inaction.

No doubt the popular press has always dramatised and personalised its stories, shifting the emphasis whenever possible from hesitation to decision. But the cult of decisive action which we are witnessing here is not just the sign of a popular (or popularising) medium. It is the hallmark of a self-consciously populist government. The traditional administrative and legisla- tive roles of government lack popular appeal: they involve procedures which are slow, boring, arcane, clogged with special- ist advice, weighed down by administrative practicalities, and often compromised by the need to resolve conflicting interests. A populist government is one which not only courts and appeals to the people (as all elective governments do), but which also pretends in some ways not to be a govern- ment. It wants to speak more directly to the people, to respond to their concerns, to act more immediately on their behalf. And since (like the people themselves, perhaps) it has little or no idea what their concerns are until it reads about them in the newspapers, a populist government has a peculiarly symbiotic relationship with the popular press.

and to take measures is to act.

Mr Hurd acts at least once a month. In December it was 'Murder on Trains: Hurd Acts'. The thugs who terrorise Britain's underground and rail networks were 'fac- ing a crackdown'. The Home Secretary was considering, it emerged, a vague string of possibilities: more video cameras, better lighting, New-York-style 'safe areas' on platforms, and so on. In January it was `Hurd Pledges Action on "Stupid Drink- ers"': A crackdown on 'stupid drinkers' was prom- ised yesterday by Home Secretary Douglas Hurd.

Employers, unions, entertainment and lei- sure industries, doctors and church leaders together with all local agencies will be asked to join the major new offensive. They needed to identify the extent of the problems locally and take joint action on the prob- lems. . .

There you have the plight of a well- meaning, would-be but can-never-quite-be Populist in all its pathos. Mr Hurd is an ambitious politician who knows that he must be seen to act. But he is held back partly by his corporatist, consensus- seeking political instincts, and partly by the responsibilities of real power: both of these factors require policies to be put into practice not by waving a wand but by going through all the humdrum procedures of Consultation and committee-forming. It is no coincidence, then, that the main sources of populism in this Government are to be found at the top and the bottom. In the middle you have the Secretaries of State and other senior ministers who, whether they like it or not, are prevented by the nature of their jobs from being true Populists — however much the Whitehall publicity machine tries to dress them up in Populist clothes. (Some of them, notably Messrs Ridley and Lawson, are enormous- ly glad to be relieved of most populist duties: Mr Ridley because populism is vulgar, and Mr Lawson because it is intellectually feeble.) At the bottom you have a new breed of deliberately vulgaris- ing, publicity-conscious junior ministers, whose role it is to troubleshoot, to 'spear- head' campaigns, to get themselves filmed and quoted. When Mr David Mellor poses with a television star sawing through a giant cardboard cigarette, he is getting the best of all possible populist worlds: voicing public concern, responding to it, symbolis- ing 'real' action (none of your dreary White Papers or scientific documents here is a man with a saw in his hand) and at the same time, sub specie aeternitatis, he is

actually doing nothing, absolutely nothing at all.

And at the top.... It is not surprising that Mrs Thatcher often seems so much fonder of her junior ministers than of her Cabinet colleagues. These are her best allies in the populist campaign. Their capacity to irritate people is construed by her as robust plain-talking; their constant appearance on radio and television is interpreted as constant action. And the Currie saga of the last three months has become a sort of political soap opera in which the Prime Minister can take a walk-on part whenever she wants it: either to tick off her erring children or to bring heart-touching comfort and solace.

Mrs Thatcher asked the beleaguered Mrs Currie: 'Are you• all right Edwina?' As the reply, 'Yes, Prime Minister', came, Mrs Thatcher uttered the words which not only kept Mrs Currie going, but told her she was right.

The Prime Minister said: 'Good, I am sure you will be all right Edwina.'

The oddity of Mrs Thatcher's position, as a brief textual analysis of the Now Maggie Steps In' story has already sug- gested, is that she both is and is not the Government. Her personal brand of populism enables her to detach herself from government actions whenever it suits her to do so. Usually it is the Govern- ment's inactions from which she distances herself, so that when ministries actually do anything she can take the credit. In recent months the popular press has credited her with 'moving' to outlaw the sale of human kidneys, 'ordering' senior ministers to co- operate with Toyota in its search for a factory site (as if their policy up to that point had been one of non-co-operation) and demanding that the Foreign Office send aid to Afghanistan (Maggie's Aid for Afghan Children'). The way these stories are presented reflects not only the stylistic requirements of vivid journalism but also the methods of her press secretary, Mr. Bernard Ingham, who is happy to attribute all decisive action to the Prime Minister herself, symbolically detaching her from the Government and then blaming mem- bers of the Government for being 'semi- detached'. Many a Cabinet Minister has woken up on a Friday morning to find `Maggie fury over minister's blunder' stor- ies in the national press. Few have had the courage or recklessness to fight back like Francis Pym, who described such smears in 1983 as 'mischief-making by the Prime Minister's poisonous acolytes'. The poison still circulates: it is part of the lifeblood of a populist Prime Minister.

Mrs Thatcher has been happy, in the past, to describe herself as a populist. Three years ago she spoke of her version of Conservatism as follows:

It is radical because when I took over we needed to be radical. It is populist. I would say many of the things I've said strike a chord in the hearts of ordinary people. Why? Because their character is independent, be- cause they don't like to be shoved around, because they are prepared to take responsi- bility....

In 1984 she said that she hoped that she had 'shattered the illusion that government could somehow substitute for individual performance'. Populism is thus identified with being anti-government. This means that it is ideally suited to radical Conserva- tives when they are in opposition. But what are they to do when they are the Govern- ment? The answer, for Mrs Thatcher, is all too easy: she can disown the lot of them whenever it suits her.

But the problem goes deeper than this. Mrs Thatcher appeals to the idea of the individual who takes responsibility and gets things done. This is, indeed, the common-sense approach to human action: if there is a problem, get up and do something about it. Populist politics en- courages people to think of the Govern- ment in exactly the same way: hence the cult of action, free from all the usual paraphernalia of policy-formation, con- sultation and legislation. Mrs Thatcher began by hitching her populism to a political philosophy of anti-statism; once in government, however, she found that those two forces were pulling in different directions. Populism may be hostile to systematic government intervention, but it is all in favour of sudden acts of intervening to solve problems, to make things happen, or (more commonly) to make things stop happening. And if the intervention is decisive enough, who cares whether it involves spending more money or making more unnecessary laws?

For years, political analysts have been trying to measure the public's attitudes on a scale which has collectivism and govern- ment action at one end, and individual action at the other. As John Rentoul shows in his study of public opinion published this week (Me and Mine: the Triumph of the New Individualism?, Unwin & Hyman, £12.95), it is difficult to find any evidence of a clear shift down the scale during the Thatcher years. Perhaps part of the ex- planation is that such a scale cannot measure the effect of a populism which favours both individualism in private life and a crude but powerful cult of govern- ment action.

There is, so to speak, an ideological schizophrenia at the heart of Mrs Thatch- er's public performance. On the one hand we have Mrs T. of Finchley, Housewife; on

the other the Right Hon. Margaret Thatch- er, Superstar. The Housewife is the embodiment of.sturdy market-town moral values, in favour of individual responsibil- ity and hostile to all forms of government control. The Superstar, by contrast, is hostile to government (her Government)

only when it fails to control things or get things done. Nothing is too difficult for her, whether it be sorting out food safety, taking action on kidneys or saving Afghan babies. 'Housewife Superstar' may be a formula for success in showbusiness — but it is no way to run a government.

Previous page

Previous page